I came to Berlin as a person with a complicated love relationship with cities. New York City often grips my heart so close it hurts. The relationship between the city and the survivor of sexual violence–or the survivor of any kind of violence or trauma–is a very particular one. Many stories and cultural narratives refer to the trope of “female intuition,” proposing that women have advanced capabilities to perceive underlying dynamics, know when and how to give love and care, and can even predict the future. Though I do believe that we occupy spiritually evolved forms, I don’t think this “higher plane” is biological. The ability to pick up on and mentally calibrate the unspoken truths that shape our lives lies in our conditioning and lived experiences with terror, with betrayal, with being hurt and punished and subdued. We are required to be alert and sensitive to our environments because we know that our physical and spiritual agency is at stake–our identities, our bodies. This is second and firsthand–learning from the experiences of other women; learning from living, through scar and callous. On the most basic level, hearing our parents tell us to be careful of strangers when we are young and traveling alone on the subway or tram for the first time. Seeing the violence done to our forms dragged as entertainment or exposé across pages of books and television screens. There is nothing natural or innate about it. Feeling the eyes the voices the eyes. The acquisition of psychic capabilities is a laborious process that involves more weight than is typically attached to “exceptional” qualities. It is a thorny gift: one that reminds me both of my own resilience and my experience of trauma.

The survivor experiences the city as a textured tapestry of seams and knots, wounds and holes that feels both as implicitly known–comforting, even–as family, and as fraught with tensions and histories as, well, family. The interactions contained within the fabric of the city are present in architecture, bodies, and the architectures bodies form when they interact, converse, and conflict. I would like to broaden the scope of the subject. The psychic qualities that I mentioned are, in my experience, gendered, and survivors are, in the context of sexual violence, often assumed to be women (most normatively assigned in media as straight white women, though straight cis white women are actually assaulted at much lower rates than their trans/PoC counterparts). The experience of the city, the experience of translation, awareness, and intuition, is by no means limited to or even most saturated around gender. The figure of the survivor in this case represents all bodies which are socially considered as objects rather than subjects; all bodies whose paths are transcribed and monitored by hegemonic agents or otherwise experience some corporal insecurity that comes with not being in total control of their most intimate beings. This refers intersectionally to queer and trans and nonbinary individuals, to the disabled and sick and neuroatypical, to sex workers, to the poor, to children and the elderly, to people of color, to the undocumented, to migrants, to refugees. All of these individuals must develop a “psychic” shield which is really just hyper-awareness. For survival.

My father, a white 6’2 man, is a prime example of a body who is not called upon to prove its worth whenever it steps foot out the door and into the “public” sphere. I love him dearly, but watching him shoulder through crowds or blunder blindly into passing individuals makes me cringe. Sometimes on the train I will consider how he is perceived, how survivor eyes drink in the learned self-oblivion and entitlement to space that comes with maleness and whiteness.

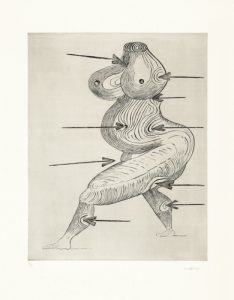

Sexual violence laid New York and all of its dynamics of flesh bare to me. I became extremely, exquisitely aware of body language. I could feel the snag of passing eyes and gauge their intentions. I felt (feel) like Louise Bourgeois’ “Sainte Sebastienne”–amorphous, read-as-female form in motion, blurring by on curved legs, the distorted swirls of flesh translating to my imagination some sort of traction, as though the figure is moving through honey. Arrows pierce Her(?) in slightly non-parallel arrangements, pinning and incising to various depths belly, heart, thigh, calf, breast, pelvis. The eyes, the voices, sometimes the touches; those agents that break through my dream of the city and make it “real,” that remind me of what I already know and have learned to feel, which do not create new wounds but simply coax old ones through their continued existence: these are the arrows. The survivor, like Sainte Sebastienne, continues to move through the city. Sometimes the arrows are even part of the path, part of the momentum and exhilaration. Either way, it is bittersweet that the city is not a Utopia. Despite the pain, the arrows save the survivor from a blank, soundless scape that they cannot relate to, cannot feel.

I wrote in my notebook, “Pure Space is the only ‘Safe’ gender.” I don’t know exactly what I meant by this. I think I meant that my body is situated intimately close to reality and craves confirmation of its realness, but also flinches from the weight of such a realization because of how history has made it tender. Maybe this is not a “normal” thing to talk about, but sexual abuse does change the way that you experience connectivity with others, or at least it has changed me. It has made it harder for me to relate to other people, or at least to pursue normative trajectories of relationships. When I need the space to be a body alone, the city is there both to welcome me and reject me. Cities both nurtured me in my post-violence state and re-exposed me time and time again to the same dynamics I associate with victimization, themes of violence and hatred against the gendered female body. But the second element of cities–their intimacy to what I see as truth, their proximity to the most unequal and mangled and rotten parts of society–also taught me. Taught me how to acknowledge histories of the body and mind without self-sacrificing. Taught me to move without dissociation. Taught me how to live without projecting tragedy or performing erasure on the corpus of memory.

I have my favorite walks in New York City and now in Berlin that make me feel like my body is dissolving and running on endlessly. In motion I am free without being remote or isolated. In New York City, I walk from Chinatown to the Lower East Side to the West side where I catch the A train. I walk from my house on 190th Street through Washington Heights and see how the microcosms of a neighborhood unfold, how the buildings morph and crumble and rebuild themselves, how blocks exhale capital or exude the city’s neglect, how visuals can be the most powerful narrators of a story. In Berlin I followed the M1 tram tracks for hours, enjoying the endlessness as well as the security that, no matter how far I went, I would not get lost. But these walks are also punctured by confrontations–being harassed on the street or seeing other people harassed; seeing the ways in which some bodies shrink to allow more space to others; seeing the ways in which some bodies shrink in order to reverse racialized and gendered assumption/be palatable for an audience; seeing the ways the condition and sanitation of streets changes depending upon neighborhood and the race and class of the people that live there; seeing how the worthiness of inhabiting bodies is etched upon buildings and in greenery or lack thereof, how devaluation is geographic and embodied and spatial and interconnected, and how the space pressing in on the individual and collective forms feels both tragic and also somehow transcendent. Watching the performance and feeling heartbroken at all the acts, yet in beautiful company. Watching the performance and feeling an odd challenge when you are not the victim, when you are actually the one taking up space. Watching the performance and performing yourself and being a part of it. Feeling oddly whole, solid, strong in how your movement continues, despite the arrows.

Tenderness does not refer simply to softness: it also, as in the case of a tender muscle, implies soreness, the presence of some pain. This is how the survivor navigates the city–tenderly, which is in itself an act of mediation. I wanted to write this as a goodbye to Berlin and to all the beautiful cities, structures, and individuals I have experienced this semester. Now I am back in New York City again, but I think my new perspective–cultivated through travel, through distance–is allowing me to experience it differently; to feel its gravity again.

The city deconstructs me and gives me back to myself. I cannot think of a better gift.

Notes:

- National Alliance to End Sexual Violence, “Racism and Rape,” http://endsexualviolence.org/where-we-stand/racism-and-rape, accessed June 2, 2017.

- RAINN, “Victims of Sexual Violence: Statistics,” https://www.rainn.org/statistics/victims-sexual-violence, accessed June 2, 2017.