On the morning of 13th of October, a small group of ECLA students gathered at the Platanenstrasse tram station, the majority of which preparing to go on a trip for their classes – Introduction to Human Rights with Prof. Kerry Bystrom, and Berlin: An Experiment in Modernity with Prof. Florian Becker. The destination: Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp. This former concentration camp is located in the small town of Oranienburg, approximately 35 kilometers north of Berlin. The trip takes a total of forty minutes to an hour at most, and can be reached by S-Bahn (Berlin’s subway).

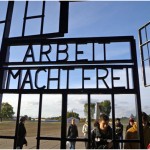

We were greeted at the memorial’s visitor’s center by our tour guide, and were immediately swept into an hour-long tour, which, in my opinion, gave a very solid background of the place. Our first stop was Tower A, or the entrance of the camp grounds. This structure, we came to learn, is the only entrance, or exit for that matter, that Sachsenhausen has. A rather typical-looking entrance to a camp, resembling its sister from the famous picture of Auschwitz not only in structure, but also in history: over 200,000 prisoners were registered in front of and passed through it. A much smaller number was able to come out, some dying of malnutrition, others of cold, and some through suicide through throwing themselves at the electrical fence.

Yet if its entrance might have looked typical, the camp itself can be called anything but that. For one, Sachsenhausen was built in the shape of an equilateral triangle, with its roll-call area (where the prisoners were counted every morning and evening) directly in the center. It was modeled, our tour guide told us, after a Panoptical – the ideal prison, where the prisoners felt exposed to the eye of the guard at all times. It was, in the words of Heinrich Himmler, the prototype of the “modern, up-to-date, ideal and easily expandable concentration camp” (1937), the ultimate symbol of Nazi oppression and terror.

Today, little has remained from the original landscape of the camp – maybe for the better, maybe for worse. Where once stood numerous barracks holding prisoners (and built by the hands of the first set of prisoners), there is now a park-like land, allowing the visitor to see camp from end to end, and thus wonder, how it is possible for such a small space to house 58,000 people at one time at its peak, held in barracks, our guide told us, that can barely hold fifty visitors today, but hosted an average of one hundred and fifty prisoners at the time – a number almost impossible to imagine to the visitor.

Our visit was brief, lasting only an hour or so. Yet, by the time our guide finished his presentation and politely said goodbye, Sachsenhausen had left a mark in our memories. It was, as the familiar words say, an experience for a lifetime.