Every once in a while, a forgotten piece of history gets the unique chance to be remembered and to resurface in the public sphere. As it happened, on December 4 a lost piece of media history got its moment: the phonograph.

I learned about the lecture through ECLA of Bard’s weekly newsletter on activities in Berlin. Organized by the Einstein Foundation, the lecture was to take place at the Museum for Communication. Although I am not usually one to leave campus on weekdays (I always feel safer cuddled next to the heater in the Library, doing my reading for the following day), the lover of antiques in me would not let me miss such a lecture. So, armed with a map and an exact address, I left ECLA of Bard’s campus and ventured into the wet from the rain streets of Berlin.

The Museum for Communication is located mere minutes away from the subway station at Potsdamer Platz, one of the most well known plazas in Berlin. From the outside, the museum looks like nothing special – just one of those large, old buildings made of stone. On the inside – yet another grand, palace-like structure that makes man feel small and at the same time swept away by the incredible beauty. Yet the Museum for Communication is even more than that. In combination with the grandiosity of the building itself, there have been placed new, modern installations, such as running text to the side of the building’s entrance and lights illuminating the interior after closing hours.

The lecture began at 7:30pm, with two short introductory speeches by members of the Einstein Foundation. The Foundation draws accomplished researchers from across the world to Berlin to do research in the fields of science, the humanities and the arts. This presentation’s lecturer had a list of credentials as long and impressive as, I suppose, expected from someone who got both his B.A., M.A., and PhD from Yale University, did many years of research and is currently a professor at Princeton. But if anyone in the nearly filled room had expected a serious, older and perhaps a bit scary professor to lecture that evening, they would have been surprised by the energetic, good-humored man who came in front of the audience.

His name was Thomas Y. Levin. His father, he came to explain, had been born in Berlin and was partly the inspiration for coming to work on this project. The project, I learned, is in the area of Media History – an area I had personally never heard about – and focused on a forgotten part of that history: the phonograph.

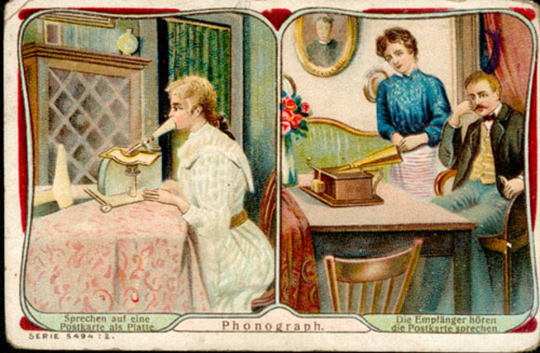

So what was the phonograph? In the 90 minutes of his talk, Thomas Levin gave a rather detailed history of the device, which first came as an idea to Thomas Edison, who imagined people creating “audio-portraits” of themselves by recording their voices through metal cylinders – an idea that was challenged by the fragility of the cylinders. Then in 1905, the phonograph made its first appearance in newspapers such as The Chicago Tribune, in the form of stories or advertisements. Between 1905 and 1906, a number of such stories appeared. Then, in 1912, a series of postcards advertising the device came out. Soon, the slogan “Don’t Write, Record It” and “Don’t Write, Speak” was spread throughout France, the United Kingdom, the United States, and eventually Germany. The device that gained the names “Voice-O-Graph” and “Die Sprachmaschine” recorded the voices of people on “digital postcards”. All one had to do was speak in the mouth piece (a cylindrical tube) of the gramophone-like device, which would in turn record the voice, and send the record through the mail. And, as the records could only be played on special devices, the industry grew more and more.

The phonograph gained special attention during WWII, when soldiers used it to send to their families what became known as “A Letter on a Record”. The records gained an emotional value, because in many cases they would arrive to the family after the telegram announcing the soldier’s death, thus becoming a reminder for the surviving family members. The phonograph was also used as a method of communication for the wounded soldiers who could not write letters.

After the war, during the 1950s, the phonograph suddenly emerged in Latin America, beginning with Argentina, followed by Brazil, Venezuela, and others. In those countries, special stamps and mailing practices for recorded letters were developed. This time, the phonograph was used to help “not only the bourgeoisie, but also children and illiterate people.” The industry was mainly fueled by American companies who produced the special machines (now booths rather than primitive gramophone-like devices). Special records, such as the Phonocord Girls by Packard-Bell, were issued. And then, suddenly, the phonograph disappeared.

The most surprising part, Levin said, was that in 1939 alone, more than 100,000 records were created. How was it that something as popular as this device, which left so many records and created such an industry, suddenly disappeared? According to Levin, there could be several explanations. The most probable one, it seems, is that with the appearance of the gramophone records, which were stamped and therefore could easily be replicated, the phonograph became impractical, as its records could not be replicated.

Yet all hope is not lost for the phonograph, as Levin’s current project focuses on creating an online database of records. Through flea markets, private research and eBay, Levin has succeeded to accumulate a large collection of records which are being digitally scanned, manipulated for bettering the quality of sound, and uploaded online. “There isn’t a day that I don’t spend on eBay, searching, bidding, and buying,” Levin said. He highlighted that, although in gradual development, the research conducted by him and his team is still in its initial stages, and that the database will not go public for a while. But when it does, the database will provide the world with a multitude of records as old as the early 1900s, allowing for the phonograph to finally take its place back in media history.