(© Staatsoper Berlin im Schiller Theatre)

In blending together the traditions of Japanese Noh Theatre with the venerable institution of Western opera, the Staatsoper’s showing of Matsukaze provides for a hauntingly pleasurable experience.

Translated from Sino-Japanese as ‘skill’, Noh theatre represents a conflation of the Japanese musical theatre tradition (dating back to the 14th century) and its 16th European counterpart. Taken together, these two finely established disciplines produced a genre of its own, evocative of each school’s particular high level of mastery. More specifically, Noh emerged out of the folk and aristocratic practices of the actor Kanami. Under his son’s tutelage (Zeami), Noh became a literary tradition (in fact, Matsukaze is considered to be his magnum opus). Following these efforts, the form of Noh takes shape. As it can be identified through the articulate combination of song, dance and spoken word into a methodical performance, each slight movement of the performer bears weighty significance as a visual expression of the overarching narrative. Deviating from traditional Western staged productions, Noh engages in an act of storytelling through visual appearances and gestures in an attempt to metaphorically represent the tale to the audience.

However, this particular production of Matsukaze, directed by Berlin choreographer Sasha Waltz is reinvigorated as a contemporary opera for a Western audience. Ms. Waltz’s choreography, for example, uses modern music of a faster tempo when setting Noh’s traditional kinetic movements to song. What twirls into this choreography and the larger experience of the opera is composer Toshio Hosokawa’s ability to emphasize the Noh-Opera merger through the composition. Mr. Hosokawa’s euphonious narrative follows a musical instrumentation that is characteristically European—with eerie strings, speech-song and rustling percussion. Yet, hints of Noh seep through the notes that each instrument plays—from the harp employed to resonate the strumming of the zither-like strings of the koto to the flute’s sedated mimic of the shakuhachi bamboo flute. As the singers sustain a note, it is difficult to misinterpret the Noh influence.

Commissioned by the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels, Matsukaze was performed in Warsaw and Luxembourg before arriving at the Berlin Staatsoper. Matsukaze, however, is not the first East-West theatrical merger. In the past century, many European composers have adapted Noh dramas, a prime example being Jasager, which despite its original existence as a Japanese morality tale was transformed into a leftist play in the hands of Bertolt Brecht.

Composer Hosokawa’s libretto might well be among the few Noh-Opera pieces that retain the original Eastern gaze. The narrative sticks to the cannon of Mugen Noh (which is characterized by the employment of spirits, ghosts, phantoms and the supernatural). As such, the time-frame is non-linear; hence the narrative disrupts the limitations of static, chronological time. This technique contributes to hauntingly disconcerting performances.

The story of Matsukaze tells of two ghost sisters — Matsukaze (meaning, ‘wind in the pines’) and Murasame (meaning ‘autumn rain’) — who await reconciliation with their lovers long after their deaths. As their souls struggle between two worlds, a traveling priest comes across their site of immanent dwelling, a vacant yet salty shore. A mysterious apparition approaches him and shares the haunting tale of the site’s infamy.

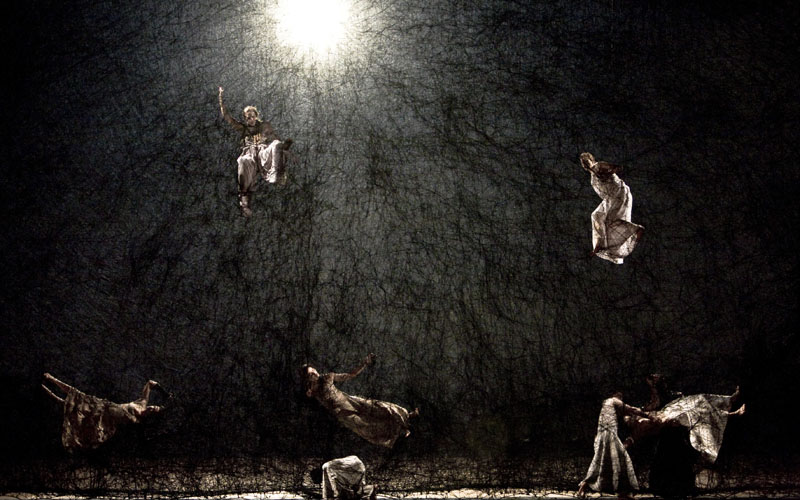

The set designs by Pia Maier Schriever and Chiharu Shiota also contribute to this eerie retelling of long lost love. The sisters’ hut is constructed without walls, reflecting on the inner life of the story, the sisters’ human lives. Half an hour into the performance, a set change transforms the stage into an artistic depiction of the sisters’ struggling souls. The sisters, portrayed by Barbara Hannigan and Charlotte Hellekant, scramble across a web of woven black thread that marks the barrier between the worlds of the vessel-less souls and humans. As the story comes to a close, another set change returns the audience to the sisters’ hut. The pillars of the hut remain intact, yet the sound of a howling storm surges into this reverie, emulating the disastrous end of the two sisters. Hundreds of long pine needles fall quickly from the sky, as eight newly added performers anxiously frolic with the sisters. An image of disaster and destruction echoes throughout.

Experiencing the haunts of such a performance is certainly daunting. Keeping in mind Noh’s vision of performance as metaphor, Matsukaze deftly burrows through its own surface texture. The ominous task lies in decoding Matsukaze’s narrative. As the sands of time pass through the sister’s plot by the sea, their loss echoes beyond their mortal existence. The union of Noh’s down-tempo movements merges well with the opera’s musical intensity. Such a contrasting union artfully blends the traditional and the modern while heralding the universal experience of loss and longing, culminating in a tension that transcends the piece and time itself.