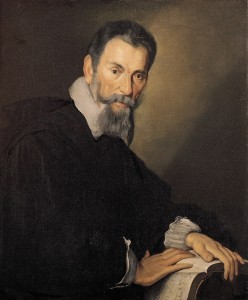

As winter brought along a festive December air, it also entrained some fervent preparation for the final papers and first semester examinations. Yet apart from rushing through our last semester weeks full to the brim with coursework, many of us sporadically adorned our challenging schedules with various activities wintery Berlin annually hosts for its enthusiastic students. Between the jolly mix of Christmas markets and travels lies a wide range of choice for us. In fact, choosing becomes a rather challenging task in itself – the manner in which we spend our free time determines the pertinence of our preferred activities to the ambitious aim we initially set for ourselves – to leverage the cultural resources the city provides. In line with my inveterate avocation, music, I have long decided to dedicate my free time to choral singing – an amateur endeavor which gradually began to acquire the hues of an aesthetic, intellectual, and social practice. Its impetus is grounded in my wish to bridge the chasm between incisive observations on aesthetics made in the academic environment and a direct aesthetic experience of music. What had been steadily outlining itself as a significant background activity to my student life in Berlin this past semester culminated on the evening of the 13th of December in the musical performance of Claudio Monteverdi’s oratorio Vespro della Beata Vergine in Auenkirche Wilmersdorf with Cantus Domus, a Berlin-based choir of dedicated and accomplished music enthusiasts.

Composed in 1610, this monumental work echoes a far more superior musical testimony to Monteverdi’s ingenuity than the composer himself and his contemporaries could have fathomed. Its purpose is left for scholars to debate – the prevalent view relates to the assumption that it served as an audition piece for work positions Monteverdi wished to obtain – while the structural order of its numbered parts is in some places rather recondite. However, apart from the fact that Monteverdi established the earliest foundations of the opera with L’Orfeo, his stylistic innovations in oratorio music likewise received wide acclaim. The focal point of Monteverdi’s Vespro della Beata Vergine, i.e. the melding of the old and new styles, renders the piece a kaleidoscopic sumptuousness. The abundance of ornamentation, which preponderantly shapes the solo lines, rather than subsuming the entire composition, subtly gives way to and graciously elevates the polyphonic vocal fabric of the psalms. Preceding each psalm are the antiphons – beautiful verses sung as plainchant* by the lower voices. And although these are not prerequisites for the overall composition and are often performed at the musicians’ discretion, they provide a contemplative contrast to the polyphonic arrangement.

Since a continual, albeit initially intermittent, interest in the Vespro della Beata Vergine revived, it has been unrelentingly occupying its place of gravitas in classical music composition and practice. It is therefore deemed a milestone masterpiece to the extent that music connoisseurs expatiate on the magnetic influence Monteverdi’s sacred works had upon subsequent compositions by our beloved music giants, such as Bach, Handel, Mozart, Verdi, to name just a few. In fact, brought about by various pertinent moments during the Vespro choir rehearsals, inter-musical associations magically made their way into those toilsome but rewarding hours of music-making as demonstrations of the opulent heritage the piece bears and of our role in bringing its legacy to new light (or rather, sound). Every so often, as we were ardently absorbed in deciphering and interpreting musical passages, occasional elucidations on the intricate web of musical ideas from the western classical canon were very much welcome, and constituted for each choir singer, I believe, an essential part of learning to relate to Monteverdi’s Vespro from a musically-sensitive performer’s perspective.

When it comes to performance practice, however, the piece leaves an interpretive gap behind, which had often been tackled by musicologists. On the one hand, they strive to dig into theoretical premises which would shape a historically appropriate interpretation in approximation of Monteverdi’s own performance inclinations and contextual (e.g. liturgical) arrangements. On the other hand, there is the endeavor to examine the implications elicited by Monteverdi’s preference to leave the score untainted by rigorous instructions regarding musical interpretation. This indeterminacy certainly left much room for improvisation on the part of music directors. The composition has been presumably composed for a ten-singer ensemble, with its solo and tutti-choir arrangements not clearly designated, thus creating much space for navigation with the vocal resources and their configuration. Equal liberties are offered to the soloists, whose choices – denotative of prowess or personal flair – are left to the singers’ interpretive preferences.

A refined and ingenious interpretation style had the performance of Cantus Domus – a rendition which boldly flowed in parallel with Monteverdi’s innovational credo, albeit rooted in a contemporary aural and cultural setting. Rather than enacting a painstaking performance based on the model of previous practices, the choir’s musical rendition exuded resplendent tonal entwinements and textures enriched by instrumental jazz elements. To add this instrumental jazzy flair, the choir set up a collaboration with the Ensemble Mosaik, Arne Jansen (electric guitar) and Daniel Stickan (keyboard), all gracefully accompanying the original vocal lines. Melding these two musical genres into a performance of Monteverdi’s sacred work may seem like quite a daring statement. And yet this decision does have conceptual and musical coherence, particularly due to a number of joint defining elements Baroque and Jazz share: improvisation – a salient ingredient for the concoction of novel sound; harmony, intricately accruing from the main bass line; and lively rhythm, endowing the piece with a blend of humbling magnitude and light-hearted play. Such a refined mingling of genres allows for a projection of Monteverdi’s inventive “spirit” upon our present time by congealing the composition’s religious themes with the secular underpinnings of jazz. Certainly, this coalescence of religious and secular, old and new style elements is already inherent in the original Vespro. And yet, there was rekindled in the choir’s performance a strong impulse to facilitate anew the sense of immediate proximity between our contemporary audience and a work that may sometimes seem obsolete. No doubt, the result was quite exhilarating.

Contriving a suitable way to approach and interpret this renowned work presupposes encountering an abundant flood of ideas that the composition elicits. Amongst these, the issue regarding the meaning of the music in relation to the words may be brought about. The assumption that there can be an intrinsic and graspable idea, whether of conceptual or religious nature, ingrained in music may lead to the following fissure: is music an art of pure tonally-moving forms (hence purposeless, and solely an aesthetic construct) or one that extends concepts, ideas, or feelings, which we could express through words, as well? As a result, a hierarchical partition between word (concept) and music often becomes imminent. This issue gained articulation in Monteverdi’s exchanges with the theorist Giovanni Artusi regarding the composer’s new style, seconda prattica. A feature of Monteverdi’s seconda prattica is mirrored in the stance the composer voiced in his “Scherzi musicali” of 1607, where he pledged for the word to be the master and not the servant of music**. Although still controversial, this position became instantiated in the dexterous way Monteverdi devised the interweavement of the three solo-lines in the reflective and echoing patterns of “Duo Seraphim”. The voices, after graciously “conversing” and mirroring one another, ultimately softly dissolve into a unity, both aesthetically and conceptually – “Pater, verbum et Spiritus Sanctus. / Et hi tres unum sunt.” (Father, word and the Holy Ghost. / And these three are one). Besides offering the listener an opportunity to grasp the religious connotations of this musical moment, here Monteverdi provides an aesthetic delight to the audience. In its turn, the choir’s interpretation included an interesting improvisation element – two of the voices were substituted by a Tenor and Alto saxophone, while the tenor soloist gracefully “sang the word”. This created an enchanting ambiance in which pure musicality paralleled the clarity of the sung words, and thus both the conceptual and musical dimensions integrated into Monteverdi’s composition were illuminated.

Another noteworthy display of the words’ role is the “Sonata sopra Sancta Maria Ora pro nobis”, where the lavish instrumental sound carves space for a simple line – “Sancta Maria, ora pro nobis” (Saint Mary, pray for us) – sung by the sopranos and seemingly reiterated to infinity. It may be heard as a musical imitation of speech, of fervent devotion in pleading and humbly-sung tones. Marked by multiple mid-phrase caesuras – interruptions in the linear flow of the sung melody – and sudden shifts in tempo, the piece hints to the disconnected and fragmentary mode in which words are uttered during overpowering visceral and spiritual experiences. The repetition of this ostensibly simple phrase endows the piece with a ritualistic aura that strips the words of any pomposity, and accentuates the sublimity of their rich content and light form. Once I internalized, as a singer, these rhythmic patterns of the piece, I began to observe beyond mere technicalities how each word and phrase acquired an individual color and significance. The phrases were no longer to be amassed as mere reiterations of the same idea, but rather as distinctive musical gestures which reflected the spiritual and musical idea from varying angles. Each repetition and intonation variation brought with it a new mode of relating to the previous, slightly differing, phrase. The breaks in between were the engulfing silence which accompanies spiritual fervor, but also which is so necessary in music-making, and can be denoted with no words.

Monteverdi wonderfully rendered the “dialogue” between utterance and silence in the sonata, yet he didn’t stop here – his composition mastery is further underscored in the dialogue-like, question-and-response patterns of the musical structures. Successive and echoed repetition is enacted in the word-play of “Audi coelum” (Hear, heaven). It is a piece that the choir inventively accentuated by further enhancing the echo effect and taking advantage of the church space and its architectural layout. Out of the main choir a number of people slowly disappeared into the dark back area of the church, leaving the rest of the choir serve as witness to the beauty of the sound to follow. As the soloist, centered amidst the “witnesses,” started singing the first phrase, a subtle divine echo resounded from the back and filled the entire space in response. The echo source was invisible, thus rendering the “dialogue” a celestial aura. It was the heavenly echo of the singer’s own word, yet altered in the form of reply:

“Audi celum, verba mea, / plena desiderio / et perfusa gaudio / …audio.”

(Hear, heaven, my words, / full of longing and streaming with joy / …I hear.)

“Dic […], / quae est ista, / […], / ut benedicam? / …dicam.”

(Tell me […], / who is she, / […] / so as to bless her? / …I will tell.)

The artfully-executed word-music pattern of Monteverdi’s composition left me wondering whether, indeed, the music was meant to act as the word’s servant, for its splendor alone would seemingly have been capable to transform the most plain of utterances into sheer beauty. My doubts were further amplified once I discovered that, according to some musicologists, the Marian Vespers setting could have applied to any saint (particularly Saint Barbara), with the exception of two pieces which suggest a reference to Virgin Mary. But little did this matter in creating a truthful relation to the music during the performance…

…A feeling of entrancement surged within me as I noticed our singing voices coagulate in limpid unified sound as a backdrop to the mysterious tones of the jazz saxophones. At that moment, the familiar jazzy timbre echoed back in an unfamiliar, strangely de-contextualized, and yet perfectly fitting color. The startling force of the distinctiveness the entire work gained through such an interpretation mode struck me at occasions of seemingly heightened subjectivity. And yet in a collective engagement to create beautiful and meaningful sound, I contentedly observed the fellow choir members’ similarly enraptured glances at moments when my perception of the music reverberated as so deeply personal. Time and again I bore witness to the fascinating power of music to unify. And while myriads of musical passages simultaneously resound with verve in the mind of every listener, what remains fascinating is that each of us is bound to perceive the color of those musical phrases differently…

Interpretation via performance therefore becomes an outpost for a further proliferation of the composer’s musical idea, while the concessions in regard to musical improvisation granted by Monteverdi to his followers may serve to encourage and advance the “spirit,” the idiosyncrasy with which he marked his work. One may carry this “spirit” forward in an endeavor to bind two different historical realms and “translate” the composer’s (musical) ideas into our contemporary setting. This would enable a palpable connection to the past via aesthetic, rather than purely intellectual, pathways. Such attempts at translation survive as long-standing evidence of music’s potential to actualize universal ideas in any given temporal and cultural frame, and thereby appeal to our human faculties – aesthetic or sensuous perceptions, rational observations, genuine emotions – wholly crystallized in floating moments when musical creation, interpretation and appreciation tune in and blend harmoniously with one another.

* A type of church music sung in medieval modes in unison. Notated in free rhythm, it is usually sung according to patterns in word emphasis. The verses are taken from the liturgy.

** In the foreword to this work, it is Monteverdi’s brother, Giulio, who adds that it was the composer’s intention “to make the words the mistress of the harmony and not the servant”. Lippman, Edward A. A History of Western Musical Aesthetics. Lincoln: U of Nebraska, 1992. 30.

Nice that you used my photos with the watermark and quote!