I am a provincial girl. I grew up in a small town. The door to the big world opened up pretty late. But it opened with a bang. I hate to admit it, but kitsch still sometimes impresses me, so do the luxurious buildings, lavish things––everything the small town did not have and never will. I am a provincial girl, I said––I don’t get used to the grandiose; its easy to impress me. Berlin never stops reminding me of my provinciality; it is why I love it. It keeps me out of my comfort zone, as we would say in Serbian, it “kicks me out of my shoes”. From all that excitement I feel butterflies in my stomach and butterflies in stomach mean love, don’t they? This is a simple story of an ordinary provincial girl impressed by the city veins, by a library. It has a lot of E in it, E-motion, E-xcitement, E-mbarrassment, E-ducat…sorry Bildung.

There are a few feelings that constantly reoccur when I am in Berlin. I feel everyone always knows where they are going; everyone is always going somewhere; there is a party that everyone knows about except me; I will never get to see ‘everything’ in this city. Perhaps it’s due to my Pankow-campus-induced laziness. ECLA has ‘breast-fed’ me since I came to Berlin. I have food, a room, books, everything I need in this little comfortable green nook of Waldstrasse. So why should I go out? Now that I am a four-year-old in ECLA years, practically almost ready to use cutlery on my own, the time has come for me to fly the nest of my carrying motherly institution and ”earn my own living and make a respectable woman out of myself”. The day has come when I needed a book—take a deep breath—from the Stabi. Stabi? Is that the building next to the cinema? The one that lurks behind the construction-like-site next to the Neue Nationalgalerie? Ahhhh, OK… so wait… how do I get a book from there?

My friend Aurelia kindly sent me instructions of her user-unfriendly library experience, and with the help of not one, but two German-speaking friends of mine, I managed to acquire a user card. Then, I proudly came to the desk with my brand new card (the photo is awful as it should be on these cards) and showed the lady a bar code of the book I needed on my smart phone, feeling so up-to-date, only to figure out that I have gone to the wrong library altogether. The lady kindly sent me to the Stabi at Unter den Linden, where the lines of Berlin blur as those of an underground cultural place with those of a metropolitan tourist-packed amusement park.

My friend had a bike, and he offered me a ride on the back of it (Holland had left its marks on both of us, I guess). ”Do you think this is allowed in Germany,” I asked, to which he said: “Probably not, they would tell you that the bike is made for one person and if you want two people on it, you need to use a tandem bike.” As we progressed from Potsdamer Platz towards Unter den Linden, I felt like I was passing through a slideshow of pictures of Berlin: Potsdamer Platz—the Jewish Memorial—Brandenburger Tor––Stabi.

”Have you ever been to the silent room?” my friend asked me. “A silent room, no, what is a silent room?” It sounded like a sort of torture chamber to me. Apparently, next to the very Brandenburger Tor, there is a room: the silent room.

The silent room is the size of a regular ECLA room, with some chairs and an art-piece-tapestry hanging on the wall. The room is soundproof and created so as to provide a place for reflection, and an escape gate from the rumble and noise of the city in the midst of which it finds itself. It’s a place where you can sit and hear nothing except your own breathing and the occasional U-Bahn noise in the distance (you cannot really expect that one could silence the U-Bahn). It’s a place where you can close your eyes for a moment and meditate on the ease that the absolute silence can provide. If you stop for a minute and ask yourself when was the last time you heard absolute silence, I am sure you would have trouble remembering it. Going out of that room was as interesting as was going in. Suddenly the city noise hits you straight in your face, but it is not unpleasant (or at least it was not for me). I felt ready for it.

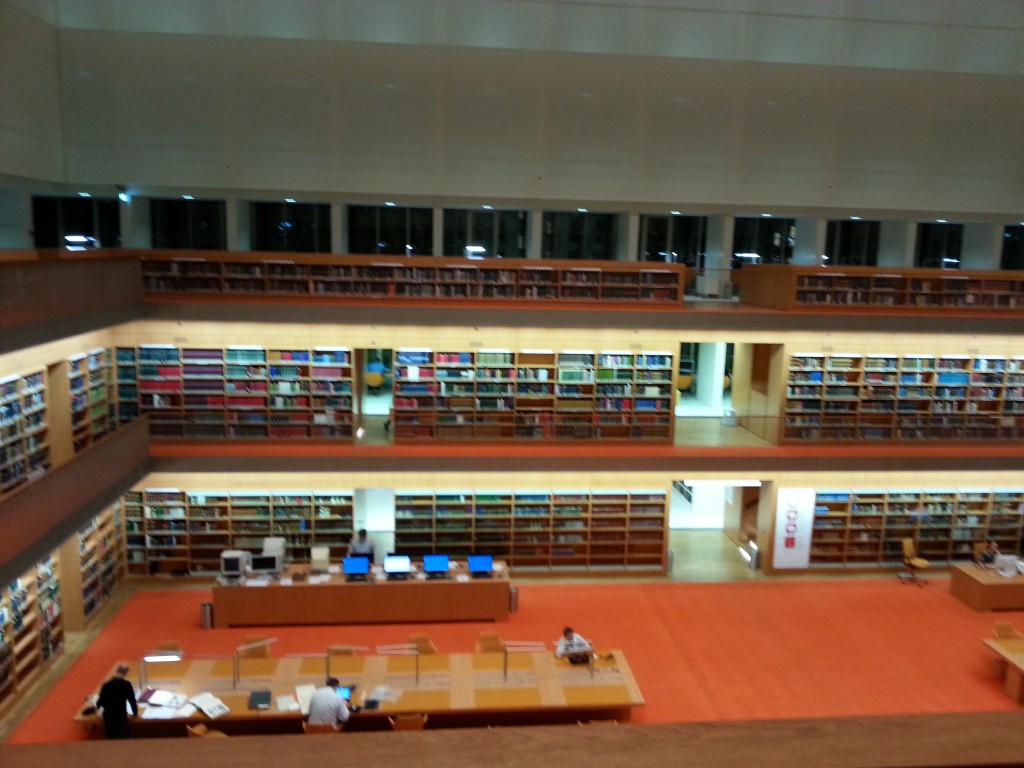

We continued our journey towards the library and soon we arrived: an old building with a circular entrance and details on the ceilings: “Wow,” said my mediocre sense of style. The entrance of the library itself was no less impressive. Even though it is as square as it can get, this gives it the sense of order and space one would expect from a library. It took me an hour to figure out their system for the sorting of books (not so much because it is astrophysics, but more because my insufficient knowledge of German led me to a couple of wrong assumptions). I spent another forty minutes figuring the logistics of how to put money on the card and scan the book I needed. Ultimately, driven by frustration and hunger, with 100 extra pages to read, I decided the day had provided me with too much information and I left.

But though I was tired and ready for ‘shut down’, Berlin wasn’t; it never is. I ran into crowds of tourists at the Brandenburger Tor, enjoying the installation that was part of the Festival of Lights that illuminated major city landmarks with various projected images or lights. I lingered for a while to see the Brandenburger Tor in rainbow colors or covered with roses. I liked it better without the lights. On the other hand, Potsdamer Platz had comic-book projections all over it, which gave it a bit of spirit. Perhaps the artificialness of light projections went better with the artificiality of Potsdamer Platz itself, and it clashed somewhat with the antiquity of the Brandenburger Tor.

I wrote in the beginning that Berlin makes me feel provincial and that is what I like about it. Most of the time I feel uninformed and slightly lagging back with all the information that lies out there waiting to be grasped—this is precisely what gives me a kick. I feel like I am constantly learning about this city as if I were here for the first time. Just when you believe there is not much else to find out, it offers something more. For me it was the library in Unter der Linden, for you it might be something else. In any case there is always something to find out. Once I was talking to a friend of mine about Berlin, and he asked me what it was that I liked so much about this city. I told him that great cities are like great people––you keep coming back to them because you always discover something new, they always have something to teach you, and something with which to blow you away; either way, you are never left indifferent.