On October 28th, a group of ECLA students got the chance to visit the temporary exhibition of works by the famous Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai at Martin-Gropius-Bau.

On display were 440 works out of his oeuvre of 30,000 which were produced over a period of 70 years. His prolific career seemed to be matched by the number of visitors to the exhibit, and everyone, both young and old, showed that they were fascinated by the display.

Hokusai was an artist of Japan’s Edo Period. At the time, Japan was isolated on the global stage, having expelled many trading enterprises from the West, maintaining connections only with Chinese and Dutch traders. The Shogunate maintained control of the country, causing monarchical rule to become purely symbolic.

This shift of power, among other factors, contributed to the rise of a bourgeois (chonin) class which profited from burgeoning commercial industries. They poured their wealth into art and culture, in turn generating increased interest in theatre, literature and the visual arts. It was in this milieu that Hokusai the artist developed and consolidated his style.

Woodcut prints primarily developed as illustrations of literary works. Woodblock carvers eventually produced these illustrations as individual prints and the technique enabled these works to be mass-produced. These pictures became known as ukiyo-e, which literally means pictures of the “floating” world—the changing and fleeting sensibility found in various subjects and settings, such as landscapes, women, figures from Japanese myths and folktales.

Hokusai, in his teen years, went into apprenticeship as a carver of woodblocks and eventually moved on as a designer of woodcuts. Hokusai’s ukiyo-e works are marked by his full use of color and of layering of multiple planes of space to create depth.

Hokusai’s development as an artist can be crudely traced using his change in name, starting out with “Shunro” as he was dubbed by his master Shunsho. He would adapt five more names (at least, those that are well-known) during the span of his career, indicating shifts in his focus of subjects, form and technique.

The exhibition was curated to reflect these changes and added some organization to the great variety of works he had done, from woodcut prints and painting to maps, art manuals and manga—all of which demonstrate an impressive attention to detail.

In Hokusai’s woodcut print of a “Green House” (a euphemism for a brothel in Japan, dating back to the practice of painting these houses in green), he depicts courtesans preparing for the New Year’s celebration. Each courtesan is wearing distinctly-designed kimonos, through which the hierarchy among the women is depicted.

There are women chatting and men preparing fire; the busyness of the figures captures the verve and anticipation of New Year’s celebrations that must have been common at the time, and such a feeling remains easy to relate to for a modern audience.

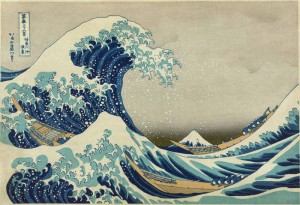

In terms of audience reception, there is perhaps none more breathtaking than his series “Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji” of which his most widely-recognized print The Great Wave Off Kanagawa is part. The Great Wave exudes dynamism as the towering wave from left seems to be seconds away from crashing down on the boats beneath it. In the center background, Mt. Fuji stands still but its shape is reminiscent of the huge waves in the foreground.

Not all prints in the series feature Mt. Fuji in its foreground, and it is interesting how many of them focus on human presence and activity instead. The series is tied together with the idea that the iconic Mt. Fuji is a symbol of nature’s omnipresence and strength.

While his landscape prints are famous and appreciated around the world, his more playful works have yet to gain mainstream popularity. One of his manga sketches the different steps of a Sparrow dance, possibly originated from the Japanese folktale “The Tongue-cut Sparrow”, while another manga illustrates what its title encapsulates: “A Hundred Coarse Jokes”.

If there is anything to take away from the exhibit, it is the incredible joy with which Hokusai imbued his works. It is hard to imagine the man as anything but jolly and free-spirited. As someone who calls himself Gakyo Rojin, literally “an old man crazy about painting”, it is easy to see why a great number of people also find themselves mad about Hokusai.

by April Matias (2nd Year BA, Philippines)