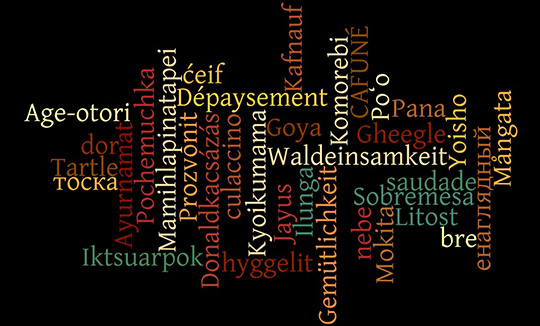

Lacunas, or semantic lexical gaps, are words whose meanings cannot be concisely translated into other languages. Some, like the Italian culaccino, refer to specific, tangible things – in this case, the mark that a cold glass leaves on a table. Others refer to emotions so particular that one experiences a kind of epiphany upon learning them. Oh, so that’s what that’s called! There is something deeply comforting about realizing that there is a word for what one has felt all along. Often lacunas cause us to feel lonely and strange, as if we are the only ones in the world to feel a certain way. Untranslatable words offer a way to bridge those linguistic and psychological gaps.

The French word Dépaysement refers to the feeling of being a foreigner that results from leaving your home country. The literal translation might be disorientation, and the closest English word would likely be homesickness, but it suggests something different altogether. Dépaysement has been a useful word for me since arriving at Berlin, because its connotation is not always negative. (Also, because every emotion, no matter how unpleasant, sounds much more romantic in French.)

I also love words like the Swedish Mångata, which refers to the shape of the reflection of the moon on water, or the Japanese Komorebi, which describes the sight of sunlight filtering through trees. These words are entire poems contained just in a few syllables.

There is another category of untranslatable words: those that describe existential states, and which may, in fact, be the hardest to explain in any language other than the original. These words are of particular interest to writers. In one of his famous lectures, Nabokov eloquently summarizes the Russian word тоска (toska):

“No single word in English renders all the shades of toska. At its deepest and most painful, it is a sensation of great spiritual anguish, often without any specific cause. At less morbid levels it is a dull ache of the soul, a longing with nothing to long for, a sick pining, a vague restlessness, mental throes, yearning. In particular cases it may be the desire for somebody of something specific, nostalgia, love-sickness. At the lowest level it grades into ennui, boredom.”

The related, but very different concept of “Litost” is prominent in the Czech writer Milan Kundera’s novel The Book of Laughter and Forgetting.

“Litost is a state of torment created by the sudden sight of one’s own misery … I have looked in vain in other languages for an equivalent, though I find it difficult to imagine how anyone can understand the human soul without it.”

This raises the question: if we were never to learn the word Litost, as, presumably, many people never will, would we fundamentally misunderstand the human soul? If we never learn the word Toska, might we never comprehend our own complex gradations of pain?

Sometimes it is not the vocabulary, but the grammar of another language that renders it difficult to translate. Nadezhda Shevchenko (BA2) explained that the Lithuanian prefix “nebe” means “no more” as in “I am no longer eating” or “I am no longer a teacher.” Even more fascinating is that Lithuanian does not distinguish between “who” and “what” because of a persisting belief that everything is endowed with a spirit.

Untranslatable words point to a kind of universal cultural aphasia. Does this mean that to better understand ourselves and the world around us, we ought to learn as many languages as we possibly can? In any case, I asked other students at Bard College Berlin for their favorite untranslatable words.

According to Aurelia Cojocaru (BA4): there is this noun in Romanian – “dor,” which expresses the intense and melancholy feeling of missing someone, which is generally considered untranslatable. It may be compared with the Portuguese “saudade.”

Mina Strugar (Bard3) told me about the Serbian interjection “bre” which, she said “every Serbian knows,” but is difficult to explain in English. One linguist has, confusingly, translated it as “I’m telling/asking you!” It has also been compared to the Canadian “eh!”

Jelena Barac (BA4) is fond of the Bosnian word “ćeif” which describes a person’s particular predilections. “It describes a sort of special hedonism or a way of enjoying something, just how you like it, i.e. drinking coffee at a certain time from a favorite cup or in some other manner because that’s your ćeif. It can also mean spite, as in, you do something just because its your ćeif to do it.”

Niv Segev (BA2) explained the Hebrew term “Kafnauf” as a person who gives very convincing, but very bad advice.

Lucas Møller (BA1) described the Danish word “hyggelit” as “like cozy… but better.” It’s a social term, one associated more with hot cocoa than with beer. It’s similar – but not quite the same – as the German word ‘Gemütlichkeit’ or the Dutch word “Gezelligheid,” which one student described as “The feeling you get when you arrive at the bar and all your friends are already there.” It’s a delightful concept, but not an unserious one. In 1973, an English solicitor was awarded damages after a trip to the Swiss Alps failed to provide the ‘Gemütlichkeit’ promised by the resort’s brochure.

Dzmitry Tsapkou (BA4) suggested the Russian word енаглядный (enaglyadny), which is “used for something (but usually a person) off whom you cannot take your eyes, or in other words you cannot get enough looking at that person/thing because of some of their exceptional quality. It often has romantic connotations.”

It’s psychologically useful, I think, to know as many of these words as possible. There is a particular irritation and sadness that comes from not having the right word to describe what you are feeling. The American poet Richard Brautigan once lamented: “I’m haunted a little this evening by feelings that have no vocabulary and events that should be explained in dimensions of lint rather than words.”

As far as I know, there is no single word, in English or any other language, that describes that feeling.