After (basically) fascists break into your country’s parliament on Thursday the 27th April 2017, you feel as if so often you’ve discussed right-wing populism in too academic of a setting. You’ve talked about the causes and cures to a movement that is only now getting underway in the West, while this is the only kind of government you ever really remember living under in your home country. You find yourself unable to intellectualize something you and many others tried to prevent. This time, you feel much more helpless, and your reaction is much more outwardly distraught. You think about how there is a debate about school policy on potentially triggering texts on campus the next day, and you wonder if any trigger warning (in the Internet meaning of the word, not the psychological one) could have prepared you for this. What would the trigger warnings for Thursday’s events have been, anyway?

TW: “Anti-Albanian Rhetoric”; “Violence against Women”; “Neo-fascism”; “Imagery that Might Make a Macedonian in Berlin Feel Powerless”.

“I feel like I don’t know what’s been happening in Macedonia lately,” your friend Anders, who’s studying in the Netherlands, tells you over Skype.

“I know what you mean. I feel like I’ve almost accidentally detached myself,” you reply, sharing his sentiment.

“No, but what is actually going on? I don’t think I get adequate news.”

“Well, the neo-fascists are still protesting. Nothing big has happened, as far as I know.” You say this as if it is a normal, everyday thing. Both of you know that Macedonia is a clientelist state where the government employs a large number of people in public institutions that it can then easily control. Because the population is poor to begin with, it is not too difficult a task to get state employees to show up to bigoted protests when their livelihood is at stake. Still, a good amount of the protesters are there of their own free will, and that’s the truly awful part.

“I saw them when I was home for spring break, and I was horrified. I thought it was just a couple of hundred crazies, but it was more 5000-ish.”

You hang up, pleased that you finally skyped Anders and are now ready to return to reading a book for class that in essence explores the guilt that accompanies one’s leaving a country behind — something you feel once in awhile. But then your brother messages you: “MA KE DO NI JA.” It is your country’s name in your own language, mockingly written in all caps and separated by syllables according to how nationalists often pronounce it. Knowing your brother, you assume something bad happened, and he, being a Slav, conveys this to you in collectively self-deprecating humor.

“What happened?” You call him, sincerely not knowing what to expect.

“You didn’t see? The nationalist morons raided the parliament. They apparently hurt a couple of MPs. Great stuff.” He says to you, obviously saddened and outraged, but still keeping his cynicism.

“Jesus Christ… And the police let them?”

“Of course they let them. They’re on their side.”

“I know… but still.” You’re mesmerized. “God, we don’t deserve a country…”

You aren’t even sure where to begin an explanation of how Macedonia got this way. The country has been under a right-wing regime for 11 years now and has only become more authoritarian as time has passed.

The short version of the story explaining Thursday’s events is that, last April 2016, the Macedonian president Gorge Ivanov decided to pardon 56 people, many of whom were high-ranking politicians who massively abused their power. This expedited events for which the seeds were sown long before. None of these politicians had been sentenced yet: they were only under investigation but were obviously guilty. This ridiculously destabilizing act led to the start of a series of months-long protests called the Colorful Revolution. You, too, were a part of this hopeful movement that united Macedonian citizens of various ethnicities, sexualities, and beliefs. They expressed their shared anger at a government that suppressed their freedom of speech, laundered their tax money, and went so far as to try to hide the murder of one of their fellow citizens — among others, ex-Minister of Interior Gordana Jankulovska attempted to cover up the brutal killing of 22-year-old Martin Neskovski by a government-aligned police officer in 2007. Martin’s death sparked the first wave of protests in 2015, and one of the biggest protests of the Colorful Revolution was held in his name on June 7th, 2016. The Colorful Revolutionaries materialized their outrage at this tragic event and myriad other VMRO-DPMNE related atrocities through vandalism, applying paint to the horrendous buildings and statues that were a part of the money-laundering architectural baroque project “Skopje 2014”. The project was the medium through which 671 billion euros landed in the hands of politicians and one that embodied fabricated nationalism. Statues of figures like Alexander the Great were supposed to perpetuate the masculinist, militarist and borderline fascist ideas about Macedonian identity. “Skopje 2014” became the symbol of the regime and the different types of paint that colored it — red, green, neons, and sometimes purple — became the metaphor for the protesters’ unity in their diverse (rather than singularly Macedonian) identities.

What the Colorful Revolution eventually led to was the President taking back his pardons, further investigations into the previously pardoned politicians’ wrongdoings, and a new election in December of 2016. Sadly, the right-wing party, VMRO-DPMNE, won by a slim majority. Luckily, they couldn’t form a government without forming a coalition with the Albanian parties. Fortunately, this time the Albanian parties didn’t want to be a part of their regime and instead wanted to form a coalition with the center-left Social Democrats who had lost by only marginally less votes than VMRO-DPMNE. Unfortunately, the president refused to give the Social Democrats the mandate to form a government – a completely unconstitutional action that resulted in Macedonia still having only a technical government. Tragically, this led to a month and a half of government-instigated protests seeking new elections, referring to Albanians with slurs and using extremely frightening rhetoric of a “pure” Macedonia. Of course, VMRO-DPMNE’s leaders do not do this directly, but rather through proxy actors, such as journalists, actual actors or supposed “independent” citizens who sell their fascist message for them. When VMRO-DPMNE can threaten its government employees with unemployment and when certain Macedonians still feel antagonism towards Albanians even after 16 years have passed since the 2001 Civil War/Conflict, it is not that hard to mobilize a group of nationalists. Yet, you were still in disbelief when you saw them by the thousands with their Macedonian flags, red-and-yellow clothing items and false patriotism walking down the same streets you had with people representing more than just these two colors.

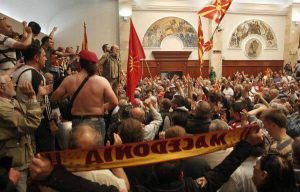

You learn that about 200 protesters — some with their faces hidden and too many with Macedonian nationalist symbols — entered the building by force after finding out that an Albanian MP had been elected President of the Parliament. You cannot believe the chaos: A hateful group shouting, breaking objects, and hurting people. You find out that one Albanian MP might be in critical condition. You watch and share a video of the opposition leader Zoran Zaev with blood spread across his face. In the same video, an old man grabs the deputy-opposition leader Radmila Shekerinska – a rather small but powerful woman – by the hair, almost slamming her to the floor. She happens to be your favorite Macedonian politician who you happened to have met at a protest once, so you watch that video over and over again, appalled every time. Your father tells you that when he saw the news he was sure that the attackers would have killed the opposition members if it hadn’t been for the lucky presence of a few personal security guards who had to go so far as to fire bullets into the air. Your mother tells you that she thought the President might have declared a state of emergency, in which case he would have gained access to military power, but thankfully didn’t. You listen to them and watch fearfully from a very safe distance, and feel guilty for not being in Skopje when it seems to be at its most vulnerable.

“This is so scary. Please stay safe,” you text Bardh, your Albanian friend who has sadly experienced harassment from nationalists, assuming that he is feeling a combination of anger, disgust, and fear right now. Just a few weeks ago he had been talking to his mom on the phone in Albanian when three of the “patriots” — rather old and probably empty men — approached him and told him that he “won’t be around here much longer.”

“Tomorrow I’ll go to Debar with my Mom for a few days,” he says, and you cannot believe that it has come to this.

You remember how many police officers there were at the Colorful Revolution protests and how there was no possible way to enter any government building. You remember the cops that looked like military with their guns, shields, and uniforms. You were a part of a fight for freedom, and you feel like you’ve lost. You see images from inside the parliament of the police nonchalantly allowing the protesters to hurt the MPs and you see photographs of cops going so far as to shake some of the perpetrators’ hands as if they were old friends — because they probably are, in fact, old friends. It was an obvious set up: The right-wing controlled police let in the people whose ideology they agreed with in a desperate attempt to cling to their diminishing power. The police officers had no intention to uphold their supposed duty. It is clear that the police protects institutions, not people.

When the Colorful Revolution broke out a little more than a year ago, 13 people were arrested while no one was injured. On Thursday evening, 102 people were injured and no one was arrested on the same night — arrest warrants for only 15 of the many aggressors, who you believe should be charged for attempted murder, only came on Saturday. This is apparently what “justice” looks like.

Despite everything, you try to be a good student and continue reading The Lowland by Jhumpa Lahiri, but in one scene one of the two main characters asks the other how he could leave to go to the US for work when so much was happening in India, politically speaking. The passage hits a little too close to home because you have left your home and now the fascists are coming and you can’t do anything but share Facebook posts and feel uneasy, and you wish that you could at least be yelling at the TV with your family there. So you stop reading the book and go back to reading the news. You wonder how a country can reconcile with itself after something like this happens – after all, you already got into a fight with a friend. You imagine a future in which even more people have made the decision to leave that you have, and you see a country with nothing but beautiful landscapes and bitter nationalists. You really hope that you could be a part of some kind of activism or journalism back home this summer that will relieve you from your immigrant guilt.

You refresh your social media accounts again and again, trying not to think of worst-case civil war scenarios, hoping for good news, but, right now, you’re not even sure what that would look like. The next day you see world media reporting: BBC, The New York Times, The Economist, even Now This. You at least feel recognized, like your tiny country took up a little bit of space in the vastness of media. Maybe if the world watches, your home will not truly descend into nationalist chaos. Maybe.

“So what happens now?” A friend asks after you explain the incidents a little too loudly in Platanenstrasse.

“I really don’t know,” you answer.

Notes:

- Macedonia parliament stormed by protesters in Skopje. BBC News. April 28, 2017. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-39738865

- Ibid.BBC. News

- Zoran Zaev, Macedonian Lawmaker, Is Bloodied in Attack on Parliament by Nationalists. The New York Times. April 27, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/27/world/europe/macedonia-parliament-attacked-nationalists.html?mwrsm=Facebook&_r=0

- Macedonian nationalists storm the parliament to hold on to power. The Economist. April 28, 2017. http://www.economist.com/news/europe/21721509-party-backed-russia-fears-losing-office-might-mean-jail-some-its?fsrc=scn%2Ffb%2Fte%2Fbl%2Fed%2F

- Nationalist protesters violently attacked members of Parliament in Macedonia. NowThis. April 29, 2017. https://www.facebook.com/NowThisNews/?hc_ref=SEARCH&fref=nf

New left oriented goverment will be in place within next 2-3 weeks, a lot of criminals will be hopefully in jail within next 6-9 months, if prooven they are guilty, That will happen next,.

In 3-4 years, if there will be a lot of hard work, and not too many mistakes, Macedonia might be good country, close to EU.