Dr. Saheb1, thank you for your time and for accepting to talk to me. How about we start with a brief introduction of you by yourself. Can you please tell us who Dr. Ahmad Ghani Khosrawi is?

Sure. I was born in 1973 in the province of Herat, Afghanistan. I completed my high school education in Herat and pursued a Bachelor’s degree in Persian Literature at Herat University. In 2006, I was awarded the Indian Council for Cultural Relations scholarship, allowing me to pursue a master’s degree at JMI University in India. Graduating with highest honors in 2008, I swiftly transitioned into doctoral studies and completed my dissertation in 2011. During 2007-2012, I served as a visiting professor at JMI University.

Over the years, I have contributed to academia in various capacities, notably as Assistant Professor and Professor of Persian Literature at JMI as well as Professor of Persian Literature and Dean of the Department of Languages at Herat University from 2012 to 2021. Currently, I offer classes on Persian Literature and Islamic Mysticism (Sufism) at Bard College Berlin. Due to the Taliban’s arrival, my family and I migrated to Germany, marking the end of my academic journey at Herat University.

I understand that you have authored many books. Could you share some highlights of your research and academic achievements?

Certainly. I have authored around 40 academic articles and 10 books which are taught as main sources in different universities in Afghanistan. My works have appeared in esteemed journals such as Ganj-e Parsi, the scientific research and coordination journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran in New Delhi; Khorshid, affiliated with the Ministry of Information and Culture, Khurasan magazine associated with the Academy of Sciences of Afghanistan, and Andisheh-ye Danish, linked to Herat State University, along with various other specialized journals.

My books have received recognition at renowned institutions such as Jamia Millia Islamia University, the University of Delhi, the University of Hyderabad, Herat University and Aligarh Muslim University.

What are you working on now?

I am about to finish writing a comprehensive book on Rumi which spans 1,500 pages and is ready for publication. Besides, currently I am engaged in a project under an agreement with Bard College Berlin, aiming to write a book on the political, social, cultural, and literary conditions of Afghanistan during the nineteenth century. This era signifies a period of caution in Afghanistan, coinciding with the British invasion. The governments formed during this time exhibit varying degrees of connection to the British, impacting their focus on power preservation rather than science, literature, and culture. Despite the presence of poets and artists, sources from this period are scarce due to the neglect of the mentioned aspects by rulers of the time.

This project is a comprehensive exploration, shedding light on a neglected chapter in Afghanistan’s history. My aim is not only to contribute to the academic understanding of this critical time but also to bring attention to the overlooked literary and cultural contributions. I aspire for the book to be translated into English, extending its reach and impact.

I should probably have started our conversation with this, but anyway, my heartfelt congratulations to you on the recent publication of a collection of your articles in Iran. Can you provide an overview of the topics covered and the significance of these articles in your field?

Absolutely, thank you! The compilation, titled From Herat to Ajmer and Tus, spans two volumes, each containing 20 articles. It is published in Iran and has received an excellent reception. Two launch events have already taken place in Iran, one in Herat, and we hope to organize one here at Bard College Berlin. The collection spans 1,200 pages, delving into diverse subjects such as Sufism, linguistics, and the interaction of the Persian language with Turkish, Bengali, Urdu, and Hindi. The title From Herat to Ajmer and Tus reflects the interconnectedness of three distinct Persian language hubs: Afghanistan, the Indian subcontinent, and Iran.

Dr. Saheb, speaking from my personal acquaintance with you and having read your works, your passion for Persian literature is truly palpable and inspiring. The way you delve into the rich tapestry of literary works, seamlessly connecting the nuances of language, culture, and spirituality, ignites a genuine enthusiasm for the subject. I would like to know what initially sparked your interest in Persian literature, and how has this passion evolved over the course of your academic career?

Initially, the expectations of my family, particularly as the eldest son, leaned towards a path in medicine—a tradition that held significance in our family. Despite this, my heart and soul resonated with a profound connection to literature.

Even as a child, poetry was ingrained in my familial environment. I vividly remember, well before my school years, expressing a keen interest in Rumi’s “Masnavi,” prompting my father to provide me with a copy. It might seem unlikely for a five-year-old to make such a request, yet this early exposure to poetry shaped my passion. During my school years, I read renowned Persian poets such as Rumi, Hafiz, Saadi, and Ferdawsi in more depth. I also read modern Persian Poetry and world fiction. I was nine years old when I wrote my first short story.

I read more Persian literary works during my high school years and this deep-rooted love for Persian literature ultimately guided my journey towards becoming a researcher and university professor.

Your academic focus also includes Sufism. What drew you to this particular area of study and how has it impacted your personal life?

Delving into Sufism, whether by choice or circumstance, triggers a profound life transformation. My initial exposure came through my discreetly devout father, a dedicated Sufi practicing self-discipline and worship. Witnessing his intense nightly rituals and occasional visits to Sufi gatherings kindled my curiosity, intensifying my interest in Sufism.

So, entering university with a foundation in Persian poetry, I professionally immersed myself in the study of Sufism during my academic journey. This opened a new chapter, involving extensive readings on Sufism’s history, Zarrinkoob’s works, and other texts enriching my grasp of Islamic mysticism.

Sufism’s focus on spiritual pursuits, transcending worldly matters, profoundly impacted my personal life. Transitioning into teaching Sufism after graduation deepened my familiarity with the subject.

My doctoral research, focused on editing Sheikh Qasim Kahi’s Divan, illuminated the social and cultural aspects of Islamic Sufism during the Mughal period. This project acquainted me with teachings from Sufi masters like Sheikh Moinuddin Chishti, Amir Hasan Dehlavi, Sheikh Naseeruddin Chiragh Dehlavi, Hazrat Khwaja Nizamuddin Aulia, and others.

The profound shift in my worldview occurred as I intimately engaged with Sufism, realizing that true human life transcends perceived luxuries, embodying the essence embraced by Sufis and Islamic mystics.

Dr. Saheb, we know that Sufis have for long encountered discrimination, persecution, and violence. Why?

The language of the Sufis or mystics has often proven challenging for individuals, particularly scholars and religious figures who prioritize outward appearances and struggle to grasp the mystic language. Consequently, a persistent conflict has existed from the beginning until today between Sufis and those devoted to outward practices. Throughout this history, Sufis have demonstrated patience and forbearance, while outward-focused scholars have often confronted them intensely, subjecting them to various injustices. Despite these challenges, both Sufis and prominent Islamic mystics have consistently endured with patience and forbearance, preventing discord from emerging.

Sufis have frequently taken initiatives to reconcile religion and mysticism, acknowledging that none of them, including Islamic scholars, were without religious affiliation. In reality, Sufis view religion as a guiding light for Sharia law. They perceive the illumination of Sharia law as essential for the journey towards truth and the path, deeming it impossible without such guidance. In the ongoing conflict between Sufis and adherents of the outward, the truth invariably sides with the Sufis, who have historically endured oppression. Despite being subject to actions and injustices incited by outward-focused adherents, the position of Sufis remains elevated and lofty, consistently aligning with what is right.

Given your focus on both Sufism and Persian Literature, how do you think these two areas are related to each other?

In delving into the study of Persian literature, it becomes evident that the essence of Islamic mysticism and spirituality permeates all masterpieces. Take, for instance, prominent figures like Ferdowsi, who, while not a Sufi or mystic, exuded a mystical essence in his works. Persian poets fall into two categories: those with a distinct mystical essence and those devoted entirely to the Sufi path. Counting figures like Attar, Sanai, Rumi, Hafez, Saadi, Khwaju Kermani, Bidel, and others reveals a cadre of absolute Sufis. Yet, even poets like Khayyam and Rudaki, while not strict Sufis, exhibit a clear mystical essence.

Attempting to separate Sufism and Islamic mysticism from Persian literature leaves little substance for the latter, as they are inherently intertwined. Khayyam, for example, embodies both kingship and Sufism, mirroring figures like Sheikh Abu Sa’id Abul-Khayr and Baba Tahir Oryan. The inseparability of Sufism, Islamic mysticism, and Persian literature is undeniable.

Persian literature’s standing today is noteworthy; among five giants of world literature, two indisputably belong to the Persian canon. Consider the impact of Hafez’s Divan, Rumi’s Masnavi, and perhaps Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. This assertion, that two of the world’s top five literatures belong to Persian, carries substantial weight. Some of the articles in From Herat to Ajmer and Tus deal exactly with the impact of Persian literature in global context, shedding light on the influence of Persian literature worldwide.

Dr. Saheb, as much as I would prefer to keep the conversation uplifting and positive, yet we all have experienced a significant transition from Afghanistan to Germany that is essential to note. Could you share more about your transition from Afghanistan to Germany?

The reality is that from 2007 to 2011, I taught and conducted research in India, accompanied by my family. Despite receiving tempting teaching offers from various universities, including some in India, as well as opportunities to migrate to Canada, America, and European countries, I remained steadfast in my decision to return to Afghanistan after successfully defending my doctoral thesis on January 8, 2011.

I resided in Afghanistan from 2011 until late 2021, dedicating myself to serving my people and homeland. Unfortunately, with the collapse of the Afghan government and the subsequent takeover by the Taliban, circumstances took a troubling turn. Incompetent individuals lacking any understanding of academic and administrative tasks assumed control of universities. The Taliban not only disrespected professors but also imposed bans on girls’ education and manipulated curricula to align with their preferences. Shockingly, they compelled professors to reconvert to Islam merely because they had taught under the government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.

Unwilling to tolerate such circumstances, I made the tough decision to leave the country.

Let’s go back to your classrooms in Herat University. You lectured in universities in Afghanistan for a very long time. Is there probably a fun or favorite memory you recall from those days?

My cherished memories are all woven around my students. One impactful moment occurred when, teaching in the journalism department, a female student who is now a diplomat, questioned if someone with only a bachelor’s degree could teach at the university. I responded that, since there were no master’s programs in Afghanistan at that time, we had to make-do with what we had. This incident, however, motivated me to pursue my master’s degree in India in 2006 and subsequently a doctoral degree, marking a fond memory. To this day, I receive messages from former students sharing their positive memories from our time together, bringing me immense happiness and gratitude for contributing to their satisfaction.

Are there any upcoming projects or developments that you’re particularly excited about?

Well, besides the research project that I mentioned earlier, I also write short stories. Indeed, during my time in Germany, I have managed to craft a collection of stories named Rain that Doesn’t Recognize Seasons, encompassing 32 tales. Written in Persian, this literary work is set to undergo translation and publication in English, courtesy of Bard College Berlin’s support. Concurrently, my dedication extends to ensuring the publication of these stories in their original Persian form.

Dr. Saheb, there is obviously much more to talk about; however, due to the brevity of time, is there anything else you would like to share about your journey, experiences, or advice for students and aspiring academics?

Please, allow me to specifically address Afghan refugees who may read this interview. Finding material comfort after years of struggle and hardship can be enticing, yet it carries the risk of being misleading, potentially causing us to forget the roots that define our identity. In order to prevent any misinterpretations of my statement, let me turn to the famous poem by Saadi Shirazi:

Human beings are members of a whole

In creation of one essence and soul

If one member is afflicted with pain

Other members uneasy will remain

If you’ve no sympathy for human pain

The name of human you cannot retain

Let’s remember that there are hundreds of thousands of young people in Afghanistan who dream of studying in developed countries. Let’s not overlook the millions of Afghan girls deprived of education within the country. With gratitude to God for the opportunity, let us make the most of the facilities and quality education we now have access to, with the hope that, in the future, we can contribute meaningfully to Afghanistan.

- Saheb or Sahib is an honorific term of Arabic origin, particularly prevalent in languages such as Persian, Urdu, and Hindi. It is used as a title of respect or courtesy, similar to addressing someone as “sir” or “mister” in English. The term is often added to a person’s name or occupation, signifying a mark of esteem or politeness.

↩︎

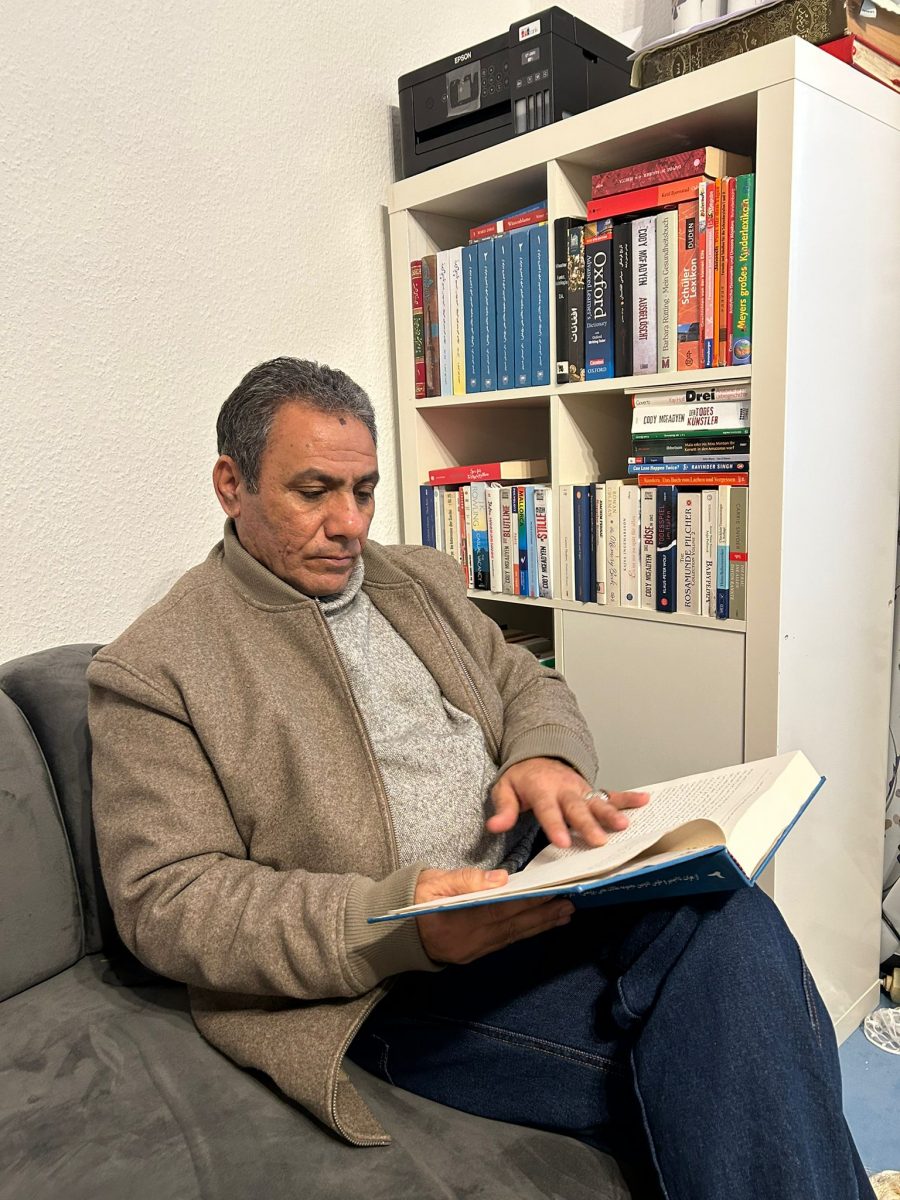

Dr. Ahmad Ghani Khosrawi provides an eye-opening glimpse into his journey and contributions to philosophy and academia. His reflections on personal experiences and intellectual pursuits shed new light on how life and scholarship interact, particularly within the complex cultural landscapes that he traverses. It’s truly impressive to witness how Dr. Khosrawi has drawn from his background to enrich his work and connect with students – making philosophy accessible and relevant to wider audiences.

Dr. Ahmad Ghani Khosrawi is a highly knowledgeable individual, and I have the privilege of knowing him personally.