“If desire [in a society] is repressed, it is because every position of desire…is capable of calling into question the established order of society…it is revolutionary in its essence…It is therefore of vital importance for a society to repress desire, and even to find something more efficient than repression, so that repression, hierarchy, exploitation, and servitude are themselves desired…that does not at all mean that desire is something other than sexuality, but that sexuality and love do not live in the bedroom of Oedipus, they dream instead of wide-open spaces, and…do not let themselves be stocked within an established order.”

— Gilles Deleuze, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia

In his essay Arab Porn (2017), the Egyptian author and journalist Youssef Rakha deconstructs an aspect of Egypt’s cultural history of the new millennium. He makes a case for how and why amateur Arab pornography acts as a political tool against the sexually repressive status quo. He attempts to account for the failures of the Egyptian Revolution of 2011 by connecting the activists’ shortcomings and ultimately frustration to the nature of Arab porn, which is reflective of the Egyptian society’s approach to sexuality, culture, politics and change. Sharing Rakha’s views, I see the Egyptian Revolution as a failed one: It replaced a military dictator with a misogynistic Islamic fundamentalist one, turning the country into a theocracy that was later overthrown in a military coup to have Egypt return once more to military dictatorship.

While Egypt does not have an official porn industry, if one searches for Arab Porn, plenty of home-made, low-quality videos can be found. Through a voyeuristic gaze, Rakha analyses various porn videos (links to which are included in his book), and draws what I perceive as far-fetched connections between the amateur porn industry, the Arab Spring in general, and Egypt specifically.

The book opens with Rakha’s account of his initial online search for porn for obvious personal reasons before launching into a description and analysis of the selection of videos that he uses to make his case. He is thorough in his description, carefully listening to any kind of dialogue between the two models and observing the setting and surrounding — be it at an old carpenter’s shop, a hospital, or simply a webcam focused on a woman’s vagina as she masturbates in bed. He notes that the weight of sexual repression enforced by religion and tradition “seems to lift, revealing a reality, if not different from the political discourse, then at least more honest” (Rakha, Arab Porn, 3). Upon reviewing the videos myself, I could not see the weight of oppression lifting at all. If anything, I could only think of the perhaps fatal consequences the women in the videos would face if the videos were found by their families or acquaintances. Rakha only briefly reflects on and then dismisses this imminent danger or the possible complete lack of agency or consent in some of videos of a young woman called Sirine. Her porn consists of her webcam focused on her vagina as she masturbates; moaning can be heard. He wonders:

Could it be that Sirine is doing this against her will? Could it be that she is displaying the false consciousness of an oppressed and exploited womanhood? It could, but her earnestness remains comparable to that of an online activist outlining the political arrangement of which he dreams. Her exhibitionism turns masturbation into an art form. (49)

Although there is no way to know for certain the reason behind her videos, they are by no means an art form, a political statement, or a means to reach female empowerment. Their purpose is to satisfy a male gaze – like that of Rakha’s. His political analysis of this pornography has absolutely no basis in reality and stems solely from his own desire to romanticize them and plug them into his narrative.

As for the other videos, Rakha doesn’t seem to take into account that the women might not be aware of the pornos circulating the sexually charged cyberspace, or even of the existence of the footage. The scandal lurking in the background is also reflected in how they act and what they say. They often have a coy, almost coquettish demeanour that caters to the male gaze and either suggests fake resistance – which is highly fetishized – or actual fear, shame or pain – eroticized attributes of the woman’s sexuality among the Egyptian collective psyche. Though I believe that pornography, such as fetish or alternative porn, can be highly political and a means to make clear emancipatory statements, I am not convinced by Rakha’s argumentation: In this case, I only see the pornography as yet another form for female oppression or a tool for masturbation.

After his analysis of at least 8 pornos, Rakha moves on to discuss how Arab sexuality operates both politically and socially as a highly charged taboo that almost everyone nonetheless explores. In an Arab society more generally and the Egyptian society particularly, non-marital sexual intercourse is seen as a sin and a massive violation of the Islamic or Egyptian mainstream morality upheld by religion and a toxically masculine culture. The burden of this is usually carried by the woman alone, whose virginal status determines male honour — be it her father’s, brother’s, or any patriarch — which explains the large number of anal-sex Arab pornos. Rakha starts drawing an analogy between Arab porn and the 2011 Revolution when he states that “online porn is to a sexually deprived individual what by 2012 the revolution had become to a politically impotent revolutionary. A matrix-borne masturbatory image. Within the reigning power structure, the one is systematically prevented from sexual self-expression, the other from political participation” (52). Thus, he compares activists’ frustrations and their fruitless resistance to the sexual frustration a sexually deprived porn viewer feels, which completely undermines the meaning of activism, resistance and political dispossession.

For Rakha, “the revolution had given birth to a new cycle of the same vicious circle: Military vs. fundamentalist repression, or a fight between two varieties of patriarch (…) Activism could not contribute to social transformation, only to the power struggles that systematically abort it” (59). While I agree with this, I attribute the failure of activism to its insistence on leaving an oppressive culture untouched and attempting to only change the political structure: These are irrevocably intertwined. However, I am not convinced that this same logic is applicable to Arab porn. Rakha draws an analogy between the wasted energy of resistance and repressed sexual energy: “Libido – instead of being released and sublimated in the interest of efficiency if not creativity – is blocked up and reduced to moral and material violence” (35). Moral and material violence in this context refers to such crimes as sexual harassment and rape within Egyptian society, which particularly affect the youth.

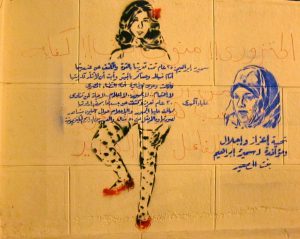

Towards the end, Rakha brings up the revolutionary activist and women’s rights advocate Aliaa El Mahdy’s nude activism during the revolution, which would later lead to her voluntary exile to Sweden where she joined the controversial feminist movement Femen (whose ideology consists in: “sextremism, atheism, and feminism” and whose goal is “complete victory over patriarchy”). While her motivation behind her famously circulated nude photograph was to liberate women’s bodies and sexuality from the objectifying male gaze, it was ultimately fetishized and circulated as pornography. Thus, her political statement was muted and her activism deemed an insult to Islamic and Arab identity by both Islamic fundamentalists as well as those fellow revolutionaries who were so hell-bent on preserving an oppressive culture founded on gender inequality and sexual repression (among other things, of course) that they would hand the country over to yet another patriarch – namely, president Abdel Fatah El Sisi.

But the connections Rakha tries to draw between El Mahdy’s resistance and amateur Arab porn are weak. As mentioned earlier, some (if not all) of the female figures in the videos lack agency and consent over the exhibitionism of their bodies and sexuality. El Mahdy’s blunt gaze towards the camera and her conscious decision to pose nude for a certain political statement differs on so many levels.

Rakha sees that revolutionaries and Arab porn models are “perpetrating an act of defiance against a stifling status quo,” (69) be it a dictatorial regime or a hypocritical mainstream moral compass. He believes the iconography of contemporary Arab reality as the imagery of a revolutionary throwing stones at the riot police is comparable with a woman masturbating on webcam. Both are ways of challenging a rigid moral and political discourse, for “desire can subvert power without having to oppose it. It can break the vicious circles, casting out religion, tradition and ideology and making pleasure accessible without the need for lies, bringing hopes and fears into perspective and the gargantuan monsters of patriarchy down to size” (70-71).

Rakha’s conclusion is an optimistic encouragement towards a secular Egyptian mindset purged of the patriarchal demons perpetuated by culture, religion, politics and tradition. He seeks ways in which channelling one’s desire and sexual energy can be a productive revolutionary weapon against the oppressive status quo. However, the basis of his book, namely the analogy of activists, revolutionaries and porn models remains unconvincing as his examples of pornography clearly reproduce a male narrative of female desire and raise issues of female consent and agency. In said examples, pornography is by no means political like El Mahdy’s activism and can even be seen as counter to an emancipatory agenda.

Along with revolutionary sexual expression such as that of El Mahdy’s or the Tunisian topless activist Amina Tyler’s controversial photographs, in my opinion, pornography in general and Arab porn specifically has the potential of functioning as a direct act of defiance against a sexually repressive regime and society. Moreover, if the hypocrisy under which Arab societies have lived for so long is finally lifted, such activists for and proponents of the freedom of sexual expression should not be seen as deviant transgressors of a culture but should be acknowledged as revolutionaries helping liberate a sexually repressed society and its creative energy.