The German Historical Museum in Berlin with its new exhibition ‘Kunst und Propaganda’ (Art and Propaganda) has grown quite popular at ECLA in the last weeks. First the ‘Continental Aesthetics’ class visited this exhibition in order to better understand the conventions of art at the time Heidegger was writing and how art changes its nature when used as political propaganda. The second organized ECLA visit was part of the ‘Seeing Berlin Programme’ when students had the opportunity to learn about history and interpretations of the artworks from a professional museum guide. Still curious about the exhibition, some students went there yet again and a full-scale ‘Art and Propaganda’ craze is now spreading rapidly among the student body. So I dare ask, why is this exhibition the favoured destination for ECLA students going into the city?

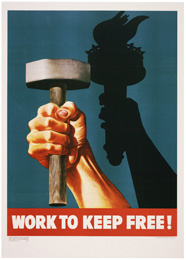

This exhibition is special because it tears down taboos. We usually think of propaganda in the terms of manipulation undertaken by totalitarian regimes. On the contrary, this exhibition tends to show that propaganda without the negative connotation it holds today is ultimately a means for political communication. The exhibition provocatively places collections from the same period (1930-1945) but from different governments side by side: Nazi Germany, fascist Italy, the USSR under Stalin and the USA under President Roosevelt. Without discerning among the types of regimes, perhaps this layout is intended to show that an institution getting its message across is not necessarily a bad thing. Before television news networks, political communication was undertaken in various other forms, including the visual arts. Even though many today think of art as a free discipline, not serving the interests of any group, observing how artists were forced to appropriate their art to fit the ideology of the government made me uncomfortable. What is more, being faced with ideas and images from before and during the Second World War period imposes a lesson on our understanding of history and politics – not everything we are told is true or justified. Questioning what propaganda means to the contemporary world, I feel, is the most powerful message this particular arrangement of artworks transmits.

The impact of the messages on society was the degree to which propaganda appealed to regular persons. Interaction with art can be a strong personal experience, but when combined with subtle or less-than-subtle messages, the outcome can be frightening. Quite wisely, the exhibition is organized into four categories: representations of political leaders, representations of society, men at work and finally – war images. This shows how one, not particularly interested in politics, could be lured into political ideology by utopian depictions of family, society, urban development, hard labour and its benefits. The images representing feelings of security and community spirit were easily appealing to a wide audience. What was previously considered to be ideology, thus became the social norm. Although a bit troubling, this exhibition was a vivid experience that stirred our critical thinking skills.

By Clara Sigheti (’07, Romania)