If you’ve recently set foot in the dorm gardens between W16 and K24, a few medium-sized boxes may have caught your eye. Once you approach, you’ll notice the signs that warn you not to get too close – you’re not supposed to disturb the bees that have been there since spring.

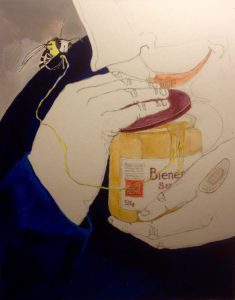

Responsible for them is Daniel Bauer, a local beekeeper who runs an apiary in the botanical garden in Blankenfelde, about 3 kilometers north of campus. I meet him in the office of the administration building to talk about his work with bees, the environment, and how the collaboration with BCB came to be one Friday morning in late August. Before we begin the interview, the beekeeper gives me a jar of honey as a sample, which I gladly take home to my apartment. By the time I sit down to type up the interview, the jar is already half empty and my fingers sticky, a result of my roommate and I shamelessly sneaking spoonfuls straight out of the jar while savoring the last days of summer.

By now the first big batch of honey has arrived at the school and is a part of our cafeteria’s breakfast buffet.

After Daniel Bauer sits down on the couch in the administration building and I have set up the recorder, he points to a small red dot above his left eyebrow that I would have otherwise overlooked: A bee sting. When I ask how often this happens, he shrugs it off with a smile and tells me that being stung is just inevitable if you’re a beekeeper, despite the fact that he wears a protective suit:

When I started, I just wore a sort of veil around my head, but the bees find a way to get through it everywhere. Then I had a jacket with a veil, and by now I’m wearing an overall, a closed suit to prevent the bees from coming through almost entirely. But it still happens occasionally, and I generally get stung around five times a day. The stinger stays in the skin, so you have to pull it out very quickly so you don’t get too much venom in the wound. But you get used to the pain.

Don’t get me wrong – every sting hurts just as badly as the first one, but you learn to look ahead and keep working rather than think about the pain. The thing about beekeeping is that you’re in nature a lot, and there is always something trying to distract you. Either it rains, or it’s cold, the bees buzz around, you get stung, but you just have to try and stay focused. And this way even being stung becomes a minor thing.

Tell me some general things about your beekeeping business.

At this point, I have around 70 bee colonies that are distributed around this area. I’m currently working up to being a professional beekeeper, and I need around 70 more colonies to be able to sustain myself with beekeeping alone.

How long did it take to build up your business this far?

It took me about 10 years, which is how long I’ve been keeping bees. I’m 40 years old now, so I have had some time to become a “real” professional beekeeper. My bee business developed rather slowly, starting as a hobby with a few bee colonies that I kept in the woods, but over time it naturally kept growing.

What was the reason you started keeping bees?

My uncle is a professional beekeeper in Austria, and so is my aunt, and they always had many colonies — around one thousand. When I was younger, I visited a few times, and I guess that’s what inspired me. When I was still at university, I acquired some bees and I liked it so much that I just kept going. And now I guess I’m on a good path to turn it into a full-time job.

What’s the process that you have to go through – from start to finish – to acquire honey?

The “year of the bee” generally ends in October. Then, it’s wintertime until March. In this time, the bees all nestle together in a ball to keep each other warm, and in that formation they slowly make their way through their food stocks — that is, the honey they collected or the food that they got from the beekeeper. And then, in April, the beekeeper takes out all the leftover food, and puts empty honeycombs into the beehive. At this time, the bees start flying and collecting pollen again. The bees’ flying radius is about 3 kilometers in each direction, so I have no doubt that the bees from BCB also make it to the botanical garden, and that the bees in the botanical garden come here.

There are several blossoming periods from April to August, starting with fruit blossoms in the spring and continuing with robinia and linden blossoms in the summer. Over the course of a few weeks, the empty honeycombs fill up with honey, and we can harvest our first ‘spring honey’ around the first of June. The second harvest is on the first of August. Then I take the honeycombs out of the beehive, open their wax seals with a kind of fork, and spin them in a centrifuge to get the honey out. After that, the honey is put through a sieve — first a coarse one, then a finer one. This way, the honey no longer has particles, which means it’s practically done. Except after a time it starts to crystallize: then you stir it with a machine and the crystals become very fine and the honey becomes creamy. At that point, it’s put into jars and ready to go on sale.

What do you find to be the most interesting or challenging thing about being a beekeeper?

What I enjoy most is that it’s incredibly interesting to think about how to deal with the bees as animals in their own right – whether I take all the honey from them, whether I leave some for them. And because I have to earn money, it’s always a thin line between taking too much and taking too little. I try to live together with the bees, so I don’t exploit them but take just enough to sustain myself. And to learn that is quite challenging and interesting. At the end of the day, it’s important that the bees are doing well. And if you reach that kind of maturity that allows you to know where to draw the line, it feels very good. It’s all about working with nature and keeping the balance. When I started, I was very immature, I made many mistakes, and I learned a lot about how nature works.

Do you have other people working with you or is it just you?

Right now a student from a university who just wants to learn something about bees independently is working with me. I’ve also had interns before, recently one from a local high school who stayed with me for two weeks. And from May to August I organize beekeeping classes, and I always get visitors who want to learn about bees or gain some practical experience with me.

It sounds like a lot of people are interested. Is that true? Do you see a trend or a tendency?

The subject of bees is currently a very relevant one in Germany, and it has been for a while. The first question I always hear from people is the question of how the bees in general are doing, whether they’re endangered. And because there is this belief, or fear, there is a large amount of interest. Generally people appreciate beekeepers because they do something for nature and for the bees. And that attitude, of course, is great for me — to have that kind of appreciation — which definitely exists in Germany.

How did the collaboration with BCB come about?

I live just around the corner, on Am Iderfenngraben, so I basically pass by this place every day. I noticed that there are a lot of blossoming linden trees in the summer. And as I was looking for a spot to put my bees, I ended up talking to the people at BCB and asked whether I could put up some bee colonies here to produce linden blossom honey. In return, I offered about 20 kilos of honey, that’s about 40 jars, as a thank-you for BCB.

Is there anything particular about keeping bees in the city?

Generally the answer to this question is that bees in the city are doing particularly well because there are a lot of blossoming plants, especially as opposed to the countryside. That’s because there are all these trees around here that were planted by the Senate. In rural areas, there is much more space that is used exclusively for agriculture, which mainly consists of monocultures, and there is virtually no room for wild-growing and blossoming plants. And, because of that, insects don’t really find a lot of nutrition in those areas. Bees have a much easier time in the city, and city honey is something quite special because there is more diversity in the plants. Though this is also a lamentable fact, in my opinion, because of course there should be habitats for bees in the countryside and not just in the city.

Did this become more of an issue in recent years? You’ve mentioned that a lot of people ask about how endangered bees are nowadays. Are they endangered?

This is actually quite a complex environmental question. First and foremost, I have to say that bees in Germany are treated as livestock, not as a wild animal. And because of that, it’s the agricultural ministry that’s responsible for the bees, not the environmental ministry. Bees are selected and bred with regards to their use for humans. This means, firstly, that they’re supposed to make a lot of honey and, secondly, that they’re easy to handle, meaning relatively calm and not aggressive. This way bees can be put in the same category as, for instance, cattle – they’re there to produce something for humans but wouldn’t be able to survive on their own because they’re bred and kept under the care of humans, with their housing provided by the beekeeper.

So, does that mean that wild bees don’t exist at all anymore?

In Germany, there are close to no wild honeybees. There are wild bees, but they belong to a different species and don’t produce honey. The honeybee, with the Latin name apis mellifera spec, doesn’t exist in the wild in Germany. So, when people ask if bees are endangered, it is actually a more difficult question than they think because bees are currently existent only in the care of humans, and it’s the beekeeper’s task to sustain them. That poses the question – are bees “extinct” when they’re not found in the wild anymore, or when they no longer exist at all? That being said, there are also attempts to de-domesticate bees, to make them more robust and capable of surviving in nature. Another problem is that because of all the agricultural areas in the countryside, there are few places for wild bees to nest, like hollow tree trunks. And because of that, bees are not able to survive in these areas. But that can change.

Do pesticides contribute to this issue?

Pesticides, of course, are another important factor, because they’re poison for bees. This goes so far that even beekeepers sometimes can’t manage to keep bees alive. Usually it’s possible for a beekeeper to ensure that the animals make it through the winter. But even us beekeepers are powerless in the face of farmers distributing pesticides. That’s another reason why bees are currently more sustainable in urban areas – no agriculture means no pesticides.

What about other kinds of pollution, such as exhaust fumes from cars, for instance?

That’s a good question. Exhaust fumes are fine dust particles. Pesticides can be measured in honey, but measuring fine dust is very expensive. I could very much imagine that honey from inner-city areas has a large content of fine dust, but the measurements to prove this don’t happen, so by definition fine dust in honey doesn’t exist.

Is climate change also making a beekeeper’s work more challenging these days?

This year I noticed that we had a very long winter, and spring started relatively late, so the bees couldn’t fly and produce honey for a long time. Essentially the ‘spring honey’ didn’t happen this year. Many colonies also didn’t make it through the long winter to the spring. So, climate change could very much become an issue — for example, if it doesn’t stop raining. This would prevent the bees from flying, which would be a huge problem. This year it already rained quite a lot, but it was still manageable. I talked to a colleague in Ireland who had to close his business because it wouldn’t stop raining. I hope this doesn’t become the case here.

Anything else you want to add?

If there is further interest in eating more honey, there is, of course, the possibility to purchase more. And if there are questions about the bees in general, I would be happy to show people around, perhaps even organize a little workshop in the spring. A few students visited me before, and if you happen to come by and I’m there, you’re welcome to talk to me and ask me questions. I’m usually there on Sundays.

The botanical garden Blankenfelde, where Daniel Bauer’s honey is also available for sale, is located at Blankenfelder Chaussee 5, 13159 Berlin. The park itself is open every day from sunrise to sunset, the greenhouses are open on Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays from 10 AM to 2 PM as well as Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays and holidays from 11AM to 5 PM. More info here: https://gruen-berlin.de/botanischer-volkspark/.

From May to August, Daniel Bauer offers beekeeping classes every Saturday and Sunday for a limited amount of participants (more info in German here: https://gruen-berlin.de/volkspark-pankow/angebote/imkern-lernen-im-botanischen-volkspark-pankow)

Daniel Bauer’s website can be found here: https://www.imkerei-im-botanischen-volkspark.de

For further questions, he can be contacted per e-mail at [email protected]