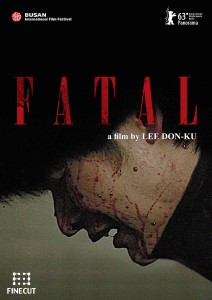

At this year’s Berlinale, South Korean director Lee Don-Ku debuted Kashiggot, a film which explores the commission, atonement and punishment of sin. In the Asian market, prolific filmmakers traditionally prefer to remain within the often painfully saccharine genre of the “Asian blockbuster.” This presents a stark contrast to Asian art-house cinema, which aims at commenting on the more nuanced aspects of Asian society. Rather than being primarily concerned with the maximization of profit through the production of trite and accessible narratives and flashy special effects, these auteurs work with a fairly small budget in an effort to focus attention on the development of nuanced storylines. Often these films are more ominously composed, as they depict violence in a rather visceral fashion. Responding to this burgeoning genre, Kashiggot’s introductory credits pay homage to the predecessors and contemporaries who made this cinematic cannon a material reality—from Park Chan Wook to Kim Ki Duk. As such, Lee Don-Ku’s film was conceived with the intention of incorporating himself and his work into the Korean art-house cinema movement. However, in spite of his best efforts, this slow-burn thriller does little to indicate that this work is worthy of such consideration.

At this year’s Berlinale, South Korean director Lee Don-Ku debuted Kashiggot, a film which explores the commission, atonement and punishment of sin. In the Asian market, prolific filmmakers traditionally prefer to remain within the often painfully saccharine genre of the “Asian blockbuster.” This presents a stark contrast to Asian art-house cinema, which aims at commenting on the more nuanced aspects of Asian society. Rather than being primarily concerned with the maximization of profit through the production of trite and accessible narratives and flashy special effects, these auteurs work with a fairly small budget in an effort to focus attention on the development of nuanced storylines. Often these films are more ominously composed, as they depict violence in a rather visceral fashion. Responding to this burgeoning genre, Kashiggot’s introductory credits pay homage to the predecessors and contemporaries who made this cinematic cannon a material reality—from Park Chan Wook to Kim Ki Duk. As such, Lee Don-Ku’s film was conceived with the intention of incorporating himself and his work into the Korean art-house cinema movement. However, in spite of his best efforts, this slow-burn thriller does little to indicate that this work is worthy of such consideration.

The initial scene swiftly envelopes the audience into the drama, as the director begins with a focus on the wrath of bullying; the film opens with four tough-talking high school boys smoking cigarettes in the kitchen of a shabby apartment. Timid Sung-gong (Nam) is hounded by his supposed friends: domineering Sae-woon (Kang Gi-doong) and his docile minions, Kyung-sang (Hong Jung-ho) and Hung-woo (Kim Hee-sung). After a few moments, the camera pans to the adjoining room revealing the source of the boys consternation—an unconscious girl lays carelessly upon a disheveled bed. The signs of rape are obvious. As the flat’s only occupant (orphaned and unattached), Jang-mi (Yang Jo-a) is an easy target for these malevolent boys. Yet, Sung-gong remains reluctant to participate fully in the rape, which inspires the others into bullying him into it. Eventually, he is thrown into the room. What follows from there is left for the viewer to merely speculate.

Cut to ten years later, Sung-gong now works in a small sewing shop in Seoul. Still in contact with his former childhood bully, Kyung Sang, our protagonist, continues to be humiliated as he leads a mundanely uneventful life—that is until he encounters a group of Christian proselytizers. Still tormented with memories of the rape and desperate for forgiveness, he seeks the aid of religion. Additionally, the viewer comes to understand that his motivations for joining the church also stem from his solitary life as an orphan. He suspects that the weight of his loneliness and guilt can be eased by the companionship promised by the church and his Bible study group. Coincidentally, that very Bible study group includes Jang Mi, the victim of his past crime. Whilst she is unaware of their past connections, he obsessively insinuates himself into her life. He gives up his job and persuades Jang-Mi to let him work at her coffee shop.

An unlikely relationship between Jang-Mi and Sung-gong develops. However, he constantly fights with his desire to tell Jang-Mi about his connection with her past traumas and with his fear that such a confession might cause him to lose the purity, kindness and joy she brings to his life. Somewhat blurring the line between romance and psychological thriller, Sung-gong’s personal drama ushers in a change in how the viewer looks upon him as a sympathetic character. In the delicate nature of his love for Jang-Mi and his infatuated kindness towards her, the viewer can be easily deceived into forgetting Sung-gong’s past and sympathizing with how he conducts himself presently. In a memorable scene, which unfolds at a beachside holiday retreat occupied by the Bible study group, Jang-Mi confesses her anguish over her desire to kill those who ruined her life ten years ago. This omission makes manifest a similar urge within Sung-gong, something that previously nestled deep within his psyche. It is from this point that the narrative (or rather the ill-fated protagonist) loses control.

The soul-baring session sets in motion a brutal chain of vengeance. Sung-gong’s existential crisis for redemption eventually spirals into a zealous quest for atonement. In an almost formulaic manner, his tale of revenge begins almost sympathetically. Unlike Sung-gong, his former friends feel no remorse. Kyung-sang is a promiscuous drunkard who continues to mistreat women; Hung-woo drunkenly harasses his subordinates; and Sae-woon, now working in his dad’s auto-shop, swindles people for money. Eventually, Sung-gong’s passion manifests as a collective act of punishment whereby every perpetrator of the past crime is killed, leaving behind a trail of homicidal and suicidal gore. After the seaside confession scene, the majority of the plot line deviates from Jang-Mi and focuses on Sung-gong’s spiraling onslaught. As the movie ends, a short glimpse into Jang-Mi’s character is offered: Jang-Mi melancholically waits for Sung-gong to reappear; she knows nothing about their shared past other than the fact that in the night prior to his murderous tirade, he professed his love for her. Whilst this scene is required to read into Jang-Mi’s character development, it leaves behind an ambiguity that is unnecessary.

The main cast, despite being constituted of new-comers, provides a major impact for the reception of the film. The acting is succinct and pulls off the delicate and dark emotional territories the narrative demands. In terms of direction, however, Lee misfires in his execution. The film reads more as an overwrought melodrama, than a significant work of subtle, emotive human drama.

In addressing the seriousness of sex crime, Kashiggot faithfully depicts its devastating effect on the delicate human psyche and human relationships. Jang-Mi is forever haunted by her past and, despite her subsequently pious behavior, wishes to kill those who did her harm. Her relationship with Sung-gong is primarily affected by his involvement in her past trauma.

In edifying Kashiggot’s plot-line, Don-Ku addresses the solution: all crime should be punished no matter what. Personally, ascribing to such a linear moral theory is far too rigid. I am also of the opinion that such a solution reduces the individuality of a person and dwells on taking advantage of a person’s vulnerability. To use the director’s negative depiction of bullying, the solution itself boils down to a morality that bullies one into succumbing to the crimes one commits, without any sense of an opportunity for redemption. Even so, to continuously argue against the narrative’s moral inclinations would be problematic if one were to call “artistic license” into question.

Sticking to Kashiggot as a product of movie making, it is evident that production values were not high. The cinematography and editing are evidently raw, which works when the film operates at its most naturalistic—though the brunt of such a disadvantage is borne by the movie’s nightmare and fantasy sequences. Contrary to the expected, however, the strange surprise came with the fact that the musical score was sparingly used. Not only did this add to the gory murder sequences, but also intensified the emotional expressions of the actors.

In aligning Don-Ku with Korean new wave directors, his focus on violence makes him a strong candidate. His narrative focuses on an experience that leaves the audience cringing at the violence, as several scenes are graphic and bloody. Yet, the protagonist’s sudden crime streak descends the narrative and the viewer into a chain of unfortunate events, that are so abrupt they hint at a lack of refinement. Jang-Mi’s ambiguous future comes off as more annoying than hopeful. She falls in love with a man who played a role in her brutal rape. Several logical leaps suggest for a formulaic and rigid moral viewing. Disciples of new wave directors, whilst impressed with Lee Don-Ku’s debut as a homage to new wave Korean Cinema, would be frustrated by the uneven narrative that depicts a lack of refinement rather than lauded meticulousness.