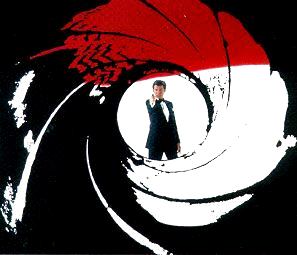

As the week was wearing off, on the Friday night of November 16, Matthias Hurst, professor of film studies at ECLA of Bard, did a thorough presentation of title sequences of James Bond movies. He covered the years 1962-2008, starting with Dr. No and ending with Quantum of Solace, thus celebrating the 50th anniversary of Bond.

As the week was wearing off, on the Friday night of November 16, Matthias Hurst, professor of film studies at ECLA of Bard, did a thorough presentation of title sequences of James Bond movies. He covered the years 1962-2008, starting with Dr. No and ending with Quantum of Solace, thus celebrating the 50th anniversary of Bond.

What one could gather from Matthias’ presentation was that the James Bond title sequences were visually fashioned in such a way that they could stand as artworks in themselves. And in possession of this quality of autonomy, they either create the structure of the film or point freely to the plot that is about to unfold.

Taking a chronological look into the title sequences, one could feel in the older ones the need to lend a helping hand to the future. Designed mostly by Maurice Binder and later by Daniel Kleinman, the animated title sequences and their aesthetics were not only well informed of the technological development of the present in which they took place; the fact that they were embedded in the present actually meant playing a double role: to help understand the potential of the present and also to participate in the creation of a futuristic vision of the world. It also seems that with the increasing complexity of James Bond’s character, the sequence titles became more intricate.

On a more intimate scale, the designer’s choice on how to visually organize the title sequence was informed directly by the plot. As seen in Matthias’ presentation, in the case of Casino Royale (2006), designed by Daniel Kleinman, James Bond is being re-invented: he is not part of the customary James Bond formula, for he is put in a position where he has to earn his status as an agent. The design of the pre-title sequence of Casino Royale is in black and white, evoking ideas of the past and in this way appealing to tradition. To paraphrase Matthias: “Picture quality seems to speak of a past, so it can build a beginning, thus saying, ‘we are aware of the past, but this is contemporary.’ ”

The film concerns itself with international terrorism and money laundering in casinos, taking place in the exotic part of Eastern Europe – the Balkans. The design of the title sequence itself remains loyal to these particular elements, employing the semiology of poker cards as bullets with which James Bond fights against terrorism.

The music, on the other hand, has a recurrent style throughout all title sequences, which contributes to constructing this bold world of Agent 007. Apparently, the question of who’s going to sing in the next James Bond movie title sequence has always triggered an immense curiosity among the audience. Being offered to do the music or sing in the title sequence, as it seemed, worked in such a way that only well known and innovative artists were invited. In this way, the James Bond franchise endowed itself with their hipness, while also acknowledging their worth. Certainly, a collaboration of the sort was a communication of value.

This tendency of double O to be always up-to-date is an important aspect. For instance, in the case of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), no artist was invited to sing for the title sequence. This was due to the fact that the late sixties introduced an innovative gadget which surpassed human vocal capabilities. Having ‘revolutionized’ the music scene with a synthesizer, the title sequences had no vocalist, but an instrumental tune for a theme.

Artists engaged with the music in James Bond throughout the years are: John Barry, Shirley Bassey, Tom Jones, Nancy Sinatra, Louis Armstrong, Carly Simon, Paul McCartney, Sheena Easton, Duran Duran, Tina Turner, Sheryl Crow, Garbage, Madonna, Chris Cornell, Alicia Keys & Jack White and, most recently, Adele.