Venezuela’s pain has grown to unimaginable heights. With the highest known oil reserves in the world, it was once the richest country in Latin America. Now, inflation soars while GDP plummets. Murder rates are at an all time high and basic medicine is barely accessible. The humanitarian crisis has led tens of thousands to leave their home. All carry a piece of that pain with them; among them, my best friend.

We met at boarding school in 2013 around the time the crisis took a turn for the worst. After Nicolás Maduro’s election that year, conditions worsened. As my friend and I grew closer, she confided in me her fears. There were feelings of betrayal and defeat, but mostly of utter powerlessness. She would stay up all night trying to stay connected. Distance takes most of your power away; the one thing you can do is stay informed. You latch onto information — reading and sharing, reading and sharing. Unfortunately, most news is bad news.

With the best intentions, 16 year-old me attempted to help. Working within my frame of reference, I treated it as I would any other heartbreak.

Of course, I didn’t quite understand heartbreak either. I told her it would all be OK, that I ‘totally’ got it, and that she couldn’t have done anything better. Needless to say, this strategy failed.

My failure is something I’m very conscious of. After high school we both moved away. The Atlantic Ocean divides us now. Nevertheless, I’ve tried to stay informed and inform others of what’s happening in Venezuela. I felt it my responsibility to carry a piece of the conflict with me.

It wasn’t until recently that I understood why I failed. Initially, I thought I just didn’t care enough. My surroundings facilitated apathy. In Europe, the coverage was little to none, and, to my understanding, the mainstream narrative was “the conflict is too far away,” and “South-America has always been messy”. This enraged me. I didn’t understand why no one cared. At the same time, it was simply easier to carry on with my life.

In retrospect, I can see how thinking no one cared was an overly simplified analysis based on frustration and a teenage entitlement. But I got one thing right: I didn’t understand. I didn’t understand the Venezuelan experience. This is why I could not be a better friend. This is why I could not make others understand.

Leaving everything you know and love behind and having it fall apart as you go is a pain most of us cannot grasp. I still don’t.

We should care. I also think a lot of us actually do. We just don’t understand. We haven’t lived it. We cannot pretend we have. If you do pretend, you impose your experience of pain on the other. By making their pain your pain, you put your pain on center stage. Pain takes different forms, many of which we cannot even imagine. How does it feel to miss food no one around you has ever tasted? How does it feel to throw away five years of university? How does it feel to not be able to have your mother hold your newborn son? How does it feel to have people pretend they ‘get it’?

I got robbed the other day. It happens to most of us at one point or another. It’s something I had talked about, read about, and seen happen. I ‘knew’ the experience. However, living it was absolutely different. It opened a completely new door of empathy. I resented all the times I had said “oh no, that sucks,” or brushed the topic off as merely anecdotal. Armed with that experience, I saw the world a little differently. There are certain experiences — like falling in love, or having someone you love die — whose intensity changes you. These experiences separate the person you are before the incident from the one you are after it.

I understand now that it was not that I had not cared. The opposite is true, and, paradoxically, my caring prevented me from helping. I was so preoccupied with trying to understand her pain through my own frame of reference that my help would always come loaded with my personal understanding of grief.

The difference between sympathy and empathy is the distinction between seeing someone’s pain and feeling it with them. For empathy, you have to be willing to get on the same level, to reach that part of you that connects to the other’s pain. This is difficult and scary. It makes you vulnerable. I wanted to feel with her and not for her; I was ready to be vulnerable. However, even my most vulnerable pain did not come close.

I thought that, to help, I had to guide her through her pain. I realize now that I was not the guide, could not be the guide: I had no idea where we had to go; I had never been there before. Even if I wanted to share her pain, I could not imagine it.

To imagine the unimaginable, you have to realize it’s exactly that: unimaginable. You will never be able to reach another person’s experience without experiencing it yourself. It’s an interesting game we play, trying to understand the other. There are certain experiences you cannot re-construct from reason. This game will not get you any closer to the other.

To imagine the unimaginable, you must accept you don’t understand. You can only let them know you’re there and that you’re willing to be guided, and let them show you the way when they are ready.

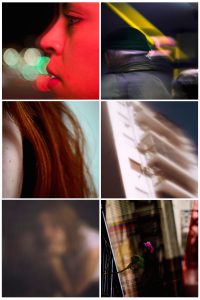

*The photographs accompanying this piece are by the wonderful Elisa Soto J., a Venezuelan photographer and aspiring filmmaker. The series presented, titled “Afuera”, is a self portrait of her life abroad: “I tried to photograph that which reminded me of my old life in Venezuela. When you’re a stranger, you never stop rummaging in the past. You long for melancholy and have to accept it has become a part of you.”

Want to see more of her work? Visit https://www.flickr.com/photos/elisasotoj