I was handed a copy of the Driving While Black Report’s Executive Summary at an East Nashville church one night in November 2016. I was born and raised in the capital of Tennessee and had recently moved home. Dozens of other people were scattered through the chapel flipping through the report, which illustrates systematic racism in traffic stops conducted by the Metro Nashville Police Department (MNPD). The report cast a harsh light on the city’s effort to rebrand itself as a liberal oasis in the middle of the Bible Belt. Despite the fact that the report draws extensively on the police department’s own data, police chief Steve Anderson moved to discredit its findings as “morally disingenuous”. It revealed that, from 2011 to 2015, during the same time that Nashville was named an “It City” by the New York Times, the MNPD conducted nearly 8 times more traffic stops than the national average, disproportionately hassling black drivers, leaving them “feeling afraid, angry, nervous, dehumanized, and traumatized”. In 70% of patrol zones, black men were twice as likely to be pulled over than white ones. The report’s conclusion called, in part, 1) for an end to broken windows policing, which is a policy conception that if police cracks down on low-level offences, then more serious crimes will be prevented, 2) a civilian oversight board, 3) a rejection of police militarization, and 4) an end to the controversial Operation Safer Streets policy, which increased police presence in minority neighborhoods. It confirmed with statistics what black Nashvillians had been saying for decades: racism was at play in the MNPD. The report warned that the “It City” was in a position to be fundamentally changed by the death of a black man at the hands of the police. Four months later, it was.

(Credit: Showing Up For Racial Justice Nashville)

Jocques Clemmons, a father of two, was 31-years-old when he was shot and killed by a white police officer in the parking lot of the heavily policed housing project James Cayce Homes on February 10, 2017. Two of the three shots hit Clemmons in the back. Within hours of his death, a memorial sprung up in the parking lot. Brightly colored balloons and stuffed animals popped out of the chain link fence where a black banner that read “SAY HIS NAME #JOCQUESCLEMMONS” was hung. Two weeks later, activists shut down a city council meeting for the first time in the city’s history, forcing the council to amend its schedule and grant protestors twenty minutes to speak. They demanded body cameras and an end to the over-policing of public housing. They demanded police chief Steve Anderson release the police report from the shooting and fire the officer who killed Jocques Clemmons. Citing the Driving While Black report, the protestors also demanded that the city instate a civilian oversight board for allegations of police misconduct.

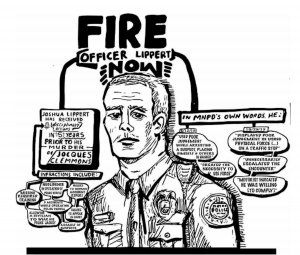

During this time, the Justice for Jacques Coalition was forming, helmed by community organizers from James Cayce Homes, Black Lives Matter activists, and Jocques Clemmons’ mother, Miss Sheila Clemmons Lee. A march from the Cayce homes to the City Hall shut down traffic at Nashville’s popular Broadway intersection. District Attorney Glenn Funk’s May 2017 decision to not prosecute Joshua Lippert, the officer who shot Clemmons, led dozens of silent protesters to the front yard of then-mayor Megan Barry’s house in the upscale Hillsboro Village neighborhood, where they left a cardboard coffin at her front gate. The NAACP, ACLU, and Jocques’ family expressed their confusion and anger at a press conference after Glenn Funk’s announcement.

“Why was one shot not enough for that officer to stop shooting [Jocques]?” Jocques’ sister, Aja Tate, is quoted by the Tennessean as saying. “Why must he continue to shoot into his body like that? Lippert is not going anywhere, it looks like, but we’re going to fight for him to get off of that force,” she said. “We’re going to fight for Lippert to get fired.”

While the community expressed its rage by occupying physical space, the police department responded by giving Lippert a slap on the wrist. Officer Lippert, who has multiple police code violations, including two instances of excessive force, was placed on paid administrative leave, then quietly moved to desk duty at the East Nashville Precinct.

Meanwhile, a proposal for community oversight was shot down in the city council, and so the Justice for Jocques coalition spread out around the city, holding meetings, press conferences and collecting hundreds of signatures so that the entire city could vote on a Community Oversight Board in the midterms. Two weeks before the deadline to submit the signatures, 23-year-old Daniel “Dan Dan” Hambrick was killed as he ran away from a white police officer during a traffic stop in North Nashville. The officer responsible for the killing, Andrew Delke, was charged with criminal homicide. Even with an officer facing legal repercussions, Nashville’s residents recognized that the violent racism of their police department had reared its head again. Signatures for the petition to nearly doubled. Two weeks later, when the ballot measure was approved the fight for Community Oversight turned into the fight for the ratification of Amendment 1. On November 6, 2018, despite a half a million dollar ad campaign funded by the largest police union in the world, Amendment 1 passed with an overwhelming 59% of the vote.

After the victory, Nick Cavin, a core organizer with the Community Oversight Now coalition, tells me over the phone:

“The moment that encapsulates this for me is when everybody was dancing to ‘Ain’t No Stopping Us Now’, but in the center were Daniel Hambrick’s mother [Vicki Hambrick] and Sheila Clemmons Lee, Jacques’ mother dancing together with tears streaming down their faces. The fact that we pulled it off showed the power of the two black women at the center of this moment, how two grieving mothers have brought massive change to this city.”

You can see the video here.

The night before the deadline to get community oversight on the ballot, my friend Josh and I decide to canvass in bars. Passing the clipboard we were using to collect signatures back and forth, we weave in and out of hordes of people drinking and laughing on a patio in my rapidly gentrifying south Nashville neighborhood. We slide next to loners on barstools, approach a group of nervously friendly undergrads, meet lots of people from out of town and talk to a group of musicians Josh recognizes. We collect pages of signatures before a manager notices and gestures us over to him. We huddle around a point of service station.

“Y’all can’t collect signatures in here,” the manager says.

“Okay, sure. But it’s not illegal,” I say confidently.

“Right,” he responds, “but you can’t do it here.”

“Oh,” I say, unsure of how to argue this point. I look to Josh.

“You want to sign the petition?” he asks.

“Yeah, of course,” the manager responds, grabbing Josh’s pen.

“I bet some of my employees would sign it too,” the manager says, wandering towards the kitchen to gather more signatures. He returns with a handful more names added to our list.

Of the dozens of people we approached that night, almost everyone who was registered to vote signed on to support community oversight.

It is close to 1:30 AM when Josh and I arrive at Santa’s Pub. Santa’s Pub is a trailer near the Nashville fairgrounds propped up on cinder blocks. The proprietor, Santa, has a long white beard and still occasionally works shifts behind the bar, which only sells beer. I sit at a table drinking a non-alcoholic Busch and smoking a cigarette. Josh gets a couple more signatures and we decide to put the clipboard away for the night. We realize we have close to 100 signatures and, anyway, Santa’s is clearing out. Someone taps me on the shoulder and gestures to the other end of the bar.

“You know that guy’s a cop, right?”

I look towards the door. A young, broad-shouldered guy with a close-cropped haircut is sitting alone. He looks like a cop. I join him at his table while Josh sings karaoke nearby. The cop and I introduce ourselves to each other.

“Have you heard about the fight for a Community Oversight Board in Nashville?”

“Yes,” he says.

“Great!” I say, “Are you interested in signing our petition?”

“Well, I’m a cop,” he says, smiling like: My hands are tied.

“So?” I ask.

“So I can’t sign it,” he says, shrugging.

It sounds final, but I crack open another non-alcoholic Busch because Josh is singing karaoke again to an almost empty bar. It doesn’t seem like the cop or I have anywhere else to be.

“You ever had a non-alcoholic Busch?” I ask.

“No,” he says.

“They taste just like regular Busch. Completely gross.”

He nods.

“Do you want to talk about Community Oversight?”

“Sure.”

He says he doesn’t like community oversight because it’s a no-confidence vote in the police department. I submit that a good portion of Nashvillians already has no confidence in the police department. He concedes and lights a cigarette. We listen to karaoke for a while.

“Listen,” he says, “If things were different, I would sign the petition, but right now everybody’s against the police.”

“You see community oversight as an existential threat to the police?” I ask.

He crushes out his cigarette.

“Yeah. Sorry.”

He leaves, and, after the last call, Josh and I leave too.

An existential threat to police. The fact that civilian oversight could be considered a threat to the institution of American policing highlights the unsalvageable position of American policing today, a rift between authority and empowered communities, that in the eyes of many police officers has rendered the two not only mutually exclusive but potentially opposed. It’s important to remember that the phenomenon the police officer in the bar referred to, that of increasing fear and skepticism towards the police, has been a phenomenon in black communities across America for decades. For generations, African-American communities have been subjected to systemic racism resulting in a dizzying combination of neglect and hyper-surveillance by the police. The Driving While Black Report, calling to mind W.E.B. Dubois’ “double consciousness” — a state of looking at one’s self through the eyes of others — calls this contradictory phenomenon “double awareness”, noting:

the fact that one is a “target” just by being a black person in America and that if one is in actual danger, police are often slow to respond. As 34-year-old Louie put it, “[W]hen I need you for a real emergency, it take you too long ‘cause I’m black. But if anything else jumps off, you right there.”

“Everyone’s against the police,” the man at the bar told me.

This, incidentally, is not true. In 2015, Gallup measured a dip in national confidence in the police but still showed that over half of Americans had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the institution.

Despite the fact that the majority of Americans have confidence in the institution of policing, disproving the bar cop’s assertion, it’s crucial to consider almost one in two Americans do not trust the police. For what it’s worth, a survey conducted by the Fraternal Order of the Police found that Nashville police officers aren’t particularly happy with their police department either. The problem of American policing is colossal. Shockwaves reverberate through the country every time an unarmed black man or boy is killed by the police, but rarely is there a collective rendering of what America could look like under a radically different system of policing. Consider the relish with which politicians speak of restructuring the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Imagine if one out of every two Americans distrusted firefighters or teachers, or nurses. Why should the system of policing be immune from such scrutiny? When a state body that is supposed to prevent violence regularly inflicts violence on its citizens, terrorizing people in their cars, homes, and neighborhoods, then the structure of how policing functions in America demands a radical reimagining, not just in left political journals, but on the national, statewide and municipal levels. Maybe one day the relationship between the police and the communities it serves can become so horizontal that the police as an institution will be entirely transformed. This hypothetical development is called police abolition.

Whether the passing of Community Oversight Board in Nashville is a model of a national move towards police abolition is up for debate. The language of police abolition was certainly not used by the campaign to get Amendment 1 on the ballot. One thing is certain: my hometown has proved that, thanks to the leadership of black Nashvillians community members, the people can go up against the Fraternal Order of the Police — an organization that supports President Donald Trump and some of the most explicitly racist police officers in the country. And we can win.

The afternoon after Josh and I stayed out all night canvassing, Jocques Clemmons’ mother, Miss Sheila Clemmons Lee, climbed the steps of the Metro Courthouse holding thousands of signatures from all over Nashville, securing a place for Community Oversight on the midterm ballot. Three months later, she and another grieving mother, Vicki Hambrick, held each other and danced, surrounded by friends and family, dancing and crying and taking videos on their phones to celebrate Community Oversight. Nearby? Photos of Jocques Clemmons and Daniel Hambrick lit up by a candle and framed by yellow and purple balloons.

Interesting piece , my name is Richard Donnell and I am collecting signatures to be nominated for one of the spots on the Citizens review board. First of all most Nashvillians are law abiding people who want to go about their business of living in a safe place and in a lawful manner. We want our communities safe like all other communities. So having a well trained police force is tantamount. Being a life long Nashvillian who has lived in public housing I have experienced encounters with law enforcement that went beyond the boundaries constitutional stop and search procedures. As a U.S. citizens I understand the need for law and order and how without law enforcement to keep order how lawlessness would escalate. I’m wanting to serve on the board to ensure that all citizens are treated the same when they have an encounter with law enforcement. Had a recent encounter with law enforcement in which I had run a stop sign at night, the officer approached and asked if I knew why I had been pulled over I said yes . He gave me a warning to not run stop signs and sent me on my way. Even if he had cited me for running that stop sign I wouldn’t have held any ill will towards that officer or MNPD because I ranned the stop sign. That’s why I’m vying for one of those slots to ensure all of our citizens are treated fairly when they have encounters with MNPD. As I said I’m looking for signatures from individuals as well as nominations from community organizations . Feel free to contact me at the email listed below.

Richard Donnell [email protected]

Excellent post.