There were new points of pain now, the body speaking verses so decisive and dense, Claudia could no longer understand the sensation. It was not a knot in the belly or a blinding headache—no, it was aches occupying the edges of words and images, unrefined and unpronounceable. Some afternoons when the winds were not so cruel, she walked the path along the ocean by her house. Her hands swayed, or she held her stomach, and glided her eyes along the surface of the ground, stopping here and there to observe those miniature twisted strangenesses of the world which only those in pain can see. A fibrous, uprooted, exhausted stalk of seaweed on the black, shiny rocks; a seagull’s scream; thinning tufts of matted yellow grass—she and these inanimate instances were performing the very same verb. The topography of agony consists of a million little dramas of nature which attest to the essential burden of reality…the atomic structure in such a place: a hand clutching the body.

Some days the suffering rope of seaweed was something comforting, as if nature had momentarily congealed its savage energies to a miracle of sympathetic form… but usually, oh god, it just felt cruel.

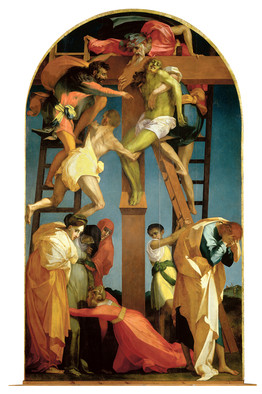

Over a tall cream cake a few Sundays ago, her mother mentioned that she would like her to go see a man she knew—he had a different sort of name, not one you hear every day or would expect a doctor to have, which Claudia couldn’t remember now as she walked the path this afternoon. She noted the perfect constellation of stones lying martyr in the grass. A flight of geese, a scattering of souls, the deposition of Christ—the very strange mannerist one by Fiorentino. The form of the stones in the grass wasn’t an echo of any real thing in the world, wasn’t an accurate composition, but rather held that curious sense of poetic torment which you feel when geese depart or in those neurotic colors of a painting. Claudia might in a healthy state have seen the very same stones and imagined the deposition, but her own image mixed up with that association would normally be absurd, where now it was inevitable. She spent too much time looking at those grotesque things of nature—getting on her knees to a seagull’s corpse, descending to the drooping riffraff of the shore.

Oh, but the landscape would mellow a bit, lose its pathetic metaphors, when she allowed herself to entertain the possibility of some miraculous resolution from the poking and prodding, analysis of the blood, and whatever new corporeal circuses medicine had recently come up with. Who was this Leonardo guy anyway?

“Cured,” pains might resign from their disorientation of her anatomy, but Claudia felt there was already irreversible injury to her condition; she had begun that fatal wrenching of mind from body, her thoughts: princess, and this terrible frame: a tower. This wasn’t right, this hardening distinction of vessel and passenger, she knew it wasn’t right. And yet she despised her body, cursed it, as if the mind were actually autonomous, a separate thing which could curse the shell it was obliged to shelter in. She felt a world without her will, the tensions of the body a demonic possession—then the mind must curse its house, despite the fact, which she knew but could not feel, that the mind is its house.

It was a distinction developed as a mechanism against madness, no doubt; were she to sense and know deeply the immaterial boundary between these entities called “mind” and “body,” there would be no way to keep those aches from absorbing her mental state as well (but hadn’t it? doesn’t it always?). The body abandoned her, she thought, now an expression of strange forces—fraying muscles braiding themselves, a belly like a schooner mast, one knee a lupine flower, the other a seal’s tremendous yawn… it was difficult to see how some specialist would solve this aspect of the problem.

Claudia turned on the path and looked back at her house which waited to greet her from the cold. There existed some architecture of comfort which belonged to her, it just wasn’t limbs-torso-head.

A cake party was held the first Sunday of every month at Claudia’s mother’s house. Claudia’s grandmother and grandfather, her aunts, uncles, cousins, siblings, and parents would gather in the sitting room and sculpt the day into another grand family memento.

Something funny would happen, people would laugh, the family would sit lingering in a plain celebration of life with a fat wedge of cake and a cup of coffee. Wasn’t it time to make that spice cake again? The one with the fluffy chocolate frosting? Oh, yes, everyone loved that one. It brought out a warmth in the chatter, the natural playfulness of community. The communion was deeply healing, Claudia’s mother thought; even one conversation disperses the body into many natural pieces, you are held whole in the mind of everyone you talk to, everyone who remembers you and cares about you, and that’s the fullest state of the human being. Leonardo was in agreement about this, he would be good for Claudia. Who you were was much more the activity of your immaterial presence than your physical presence. And it was important to strive to be present in people even when your body was far away, to do things for others, be at the origin of some goodness happening remote from you. And you really couldn’t do this staying cooped up in a mind contemplating itself.

Claudia’s mother imagined her on those walks which she mentioned were a real positive force in her life.

“I see things which make me feel at peace with it.”

“Let me take you to Leonardo, Claudia.”

“Mm, okay, but it really won’t make a difference.”

Of course, it would make a difference! Even making the trip to see the man, talking to someone who sees bodies differently, this would be so helpful.

These family rituals, Claudia’s mother thought as she stirred the frosting, they’re good for a broken heart, and everyone has some bit of them broken or forgotten in an obvious place. Then you see the people who are like you and who are you and you remember something basic about your nature. That simple reassuring fact that Claudia has her grandmother’s long noble nose, and Marta laughs just like her sister, and Edward savors each bite because that’s what his father taught him to do.

Claudia’s mother began grinding batches of coffee beans, the kitchen folding into the velvet of that magnificent aroma. This was a special bean she’d bought, expensive, but of course the humble gathering was worthy of such richness. Any moment might be made special, given that singular silkiness the mind reserves for a thing which will become a sweet memory, given unique form by those small sensual variations…she believed something like delicious coffee could do that. Her daughter would love this coffee, she thought. Oh, but where was I, could I get Leonardo to come to the cake party?—the buzz of the coffee grinder had stunted the thought for a moment but she picked it up again.

Claudia’s father slid his finger around the circumference of the cake stand and stuck the fluff of frosting in his mouth, sucking, and saying in his soft way, “mmmmmm.” Claudia’s father knew not to linger in the kitchen, he was always in the way, so returned to the front porch where he patted the dog’s head and hummed to himself. His gaze drifted off into the infinite dawning and disappearance of identifiable form in the clouds, he didn’t notice at first the neighbor as he approached the front stoop. The dog growled and Claudia’s father left the perfect cumulous octopus to greet Mathew. He was glad that it was Mathew, who would appreciate a cloud cephalopod.

“Hey, do you see that one?” he said pointing up. Matthew sat down beside him and leaned back.

“Octopus?”

“Yeah.”

There were some people who could just see what you saw, it didn’t mean you agreed on everything, just that some quality of the world was apparent to both of you, and there was something to that, Claudia’s father thought. Mathew was one of those people for him.

“Are you staying for the cake party, Mathew?”

“Ah no, Hilda and I are going over to help Ada and John with the baby.”

“Ada’s recovered well from the operation?”

“More or less, she’s feeling quite weak but her spirits are improving significantly. John was so good, it’s great that she has John.”

The sinewy white gathered ribs and vertebrae for the brief summoning of a fish skeleton in the blue sky.

“Spine of a fish, you see that one?” said Mathew.

“Yeah,” said Claudia’s father.

“And how is Claudia?”

“Sick again, or sick more than before. I sometimes wish she had someone like John, someone to take care of her—a profile of a man sitting on a throne, see it?—But in many ways, she’s got a spirit like mine—oh! A woman cradling her child!” Mathew saw it and also knew what Claudia’s father meant. The men would speak very frankly about such things in their lives, the health of their daughters, an openness which was a rarity in men in town.

“She makes a lot of theories,” Claudia’s father continued, “as if it was a puzzle. Maybe it is all a kind of puzzle but not one to be solved with logic.”

“And you don’t mean she’s thinking about medicine,” Mathew responded. Precisely, he didn’t mean medicine. It wasn’t the world’s reserves of established scientific truths of which Claudia was in dedicated orbit, but some strangely unembodied questions of will and inspiration which had nothing to do with needles and pumps. Some people believe, not even fully consciously, Claudia’s father thought, that beauty could cure you. Not the aesthetics of surface, but the serious pleasure of spending time with the world, feeling a biology which ruptured the boundaries of the body and was in communion with the whole of things… those poetic insights which could sustain. What he meant about he and his daughter sharing a spirit was concerning some stubbornness about how the world takes you in, because sometimes it’s really unpleasant, sometimes that natural communion with the whole of things was about pain and wasn’t anything to try to reason elegantly into the narrative of one’s life.

“You let me know if there’s anything I can do for her,” Mathew added after a warm curl of silence, “there’s nothing wrong with being alone, but it doesn’t hurt to have someone to talk to sometimes, point out a few things you’d otherwise miss. Not sure I’m the guy to do it, but I’d be happy to visit her out there.”

“Friends are one body with two sets of eyes, right.”

“That’s right.”

If friendship was about seeing things better, about deepening the experience with the out-there, maybe it was better that Claudia was alone, to figure out what it was to be in-here, to be a body uncomfortable. But what were the costs of such realizations? Hm, I don’t know what’s best, Claudia’s father thought. But Leonardo might be coming, and he could see the body in perfect harmony, as if the fine line of nature were in his very eye. He would have something interesting to say.

Claudia’s mother carefully carried the two Sunday cakes from the kitchen to the sitting room, spice cakes with light swoops of chocolate frosting and whipped cream in small bowls. The cousins, aunts and great aunts, uncles and great uncles gathered around the temptation of the afternoon, all except for Claudia’s father and her uncle Max, who had their hands glued to their chins as they stared down at a chessboard in contemplative trance. “It’s time for cake!” Claudia’s mother said right in Claudia’s father’s ear, he turned with a great smile on his face, ready to be warmed by the spices and the amusing hokum of family chitchat. He never took it too seriously, learned in his early days of marriage to find the energized banalities of this family not inane (or not only inane) but somewhat charming. Mostly he just sat eating his cake and enjoying it, without paying much attention to the gaudy and trite family rundowns.

The cousins talked about their studies, summer plans, the best kind of milk to drink with cake, books they were reading. Marta was complaining about her skin, in a way that confirmed to Claudia how vain she was. Somehow a thing like that could never just be a fact filed away and accepted, that this cousin was vain and obnoxious, it was always a bothersome revelation that Claudia brooded over unnecessarily. But while small vices like this deeply aggravated her, how people just smiled and nodded at such frivolous and frothy anecdotes, those small virtuous triumphs of people moved her just as strongly. Peter, who was still in high school, mentioned how his friends had brought him a big chocolate cake during math class which they had made him for his birthday, “a bit like this one,” he said pointing to Claudia’s mother’s cake, “but, not as good.” People laughed and enjoyed this little story, but Claudia loved the matter-of-factness with which he told it. She could think about a beautiful moment like that for a long time, the goodness of the world touched at so directly and with such effortlessness. To be good was effortless.

Her three large-bottomed aunts, nodding and knitting, sat side by side on the same small sofa they always sat on, unaware of or indifferent to the fact that time had brought their once small frames closer and closer together on their Sunday seat. They looked incredibly uncomfortable all squished together—but they weren’t.

Claudia always felt a little uncomfortable at these monthly gatherings herself—she felt a bit uncomfortable everywhere. As long as no one had that horrible look on their face—I wonder what’s wrong with her—she could enjoy the company. Or rather, as long as she didn’t catch them in the act, those soft and concerned glances weeping over a soft slice of cake or glinting in the tines of a fork. Those secret attempts to solve her, the way people thought that enough concern would soothe her, bothered her deeply. And of course, her health was frequently coming up these days.

“How are you feeling?” asked Claudia’s grandmother.

“The pain comes and goes.”

Claudia knew not many more details were necessary to get the family going on solutions and declarations on the plot of this melodrama of her health. Of course, she didn’t want to be a story, because then she was some abstract and distinct entity, she was something to consider and be stimulated by rather than to be related to. She really hated being that tasty bit of gossip which got the family members salivating, something Claudia’s mother assured her she was not, and something Claudia’s father smiled silently about knowing that there was a bit of truth to this. The more honestly she spoke of her state, the bleaker her life appeared to them and the more the audience would be titillated—“that’s just not true,” said Claudia’s mother. But the other option was coddling her listeners, to keep herself from becoming the pathetic young wanderer in the family epic, and to keep those rare few who had that ability to relate to the other from the pain of empathy. “You shouldn’t be so worried about what other people feel for you. You shouldn’t be worried that people worry about you,” her mother said. Worry and care felt different to Claudia, worry was like an imitation of care, a badly rendered miniature figurine, while care was something spiritually unruly, beyond customs and propriety, hitting the heart directly.

“The pain comes and goes,” she said again.

The doorbell rang and Claudia’s mother stood up to greet three new visitors. From the hallway Claudia could hear her mother’s warmth, her lovingness towards her guests heaping in each soft word and in the way she shepherded them to the sitting room. Ben and his new girlfriend entered with the wonderful big “hello” of those hung from high firmaments of new love. Then Claudia’s mother brought in a man the same age as Claudia’s father with round glasses and silver hair, who she introduced as Leonardo. The members of the family greeted the newcomer with great, perhaps too great, delight, and then returned to the important matter of Claudia’s wellness which certainly could be solved this afternoon with all the minds in this house. The man sat between Marta and Edward, Claudia’s mother handed him a plate of cake and he nodded in gratitude.

“My neighbor was telling me about this tea,” one of Claudia’s large-bottomed aunts said, “which is supposed to really ease pain. So, I tried it, I’ve been drinking it every night for my knees—with a little honey and milk—and it’s really quite amazing, it’s not a complete remedy but I swear it’s alleviating.” She tapped her large knees together as if to prove the tea’s generous power.

“It’s best to get regular exercise and eat well,” said an uncle. Claudia’s father added in a rare chiming-in, “and sleep and dream well.” Claudia’s mother added in her characteristic sincerity, “and be amongst family.” The family went on listing all the typical wisdoms of health, threading stories of pains and triumphs of the body, some distastefully braggadocious, as if the problem was a lack of ample strength in conquering the ailment, a lack of mental fortitude.

The pain hadn’t made her lose her sense of purpose completely, Claudia thought, she still knew what she wanted and what was worth considering in the world in an abstract sense, it was rather that raw intuitive feeling part, the gut-level wonder before we can explain the thing, the sublime blows of the world—it was this which had dulled with her pains. What was sleep and exercise and family then? It was the remedy, they were insisting, but Claudia was an endless winding sigh which breathed right through such simple solutions. This time, the spice cake indeed opening her up a bit, she was able to palate such obvious and obtuse advice by appreciating some serious worldview behind each flimsy road to health proposed.

“But, couldn’t this tea be a placebo?” Peter asked of the aunt’s magic tea from the beginning of the conversation.

“Oh certainly,” the aunt replied, nodding her head vigorously, “but that doesn’t really matter.”

“Like acting healthy,” said Claudia in a rare chiming-in.

Then, from between the arrogant Marta and the cake-savoring Edward who was still on his first piece after many hours, the stranger had a strange look on his face as if suddenly remembering something he’d forgotten. He said in a soft, squeaky voice, “no one considers their natural condition to be the sick one, or considers aching a natural state of being.”

The whole family turned to look at the man, save for Marta, who twisted her neck in the opposite direction to braid her hair, and Claudia’s father, who was staring up at an invisible chess board, plotting his next move. Leonardo hardly moved as he spoke, balanced the shiny white plate of chocolate cake on his thin knee. He very gracefully swept his eyes across the room like a hand slowly conducting; his gaze glided from face to face, as if examining their attention or searching for some flicker of active being, as if taking a pulse…He continued in his steady, sweet voice.

“So, acting healthy is a way of acting like oneself when we feel sick, when we are estranged from the normal state of the body. Being sick, we feel lost and we pretend to be as we were in health in hopes that we will find that more authentic way of being again.” One of the plump aunts closed her eyes and nodded with an “mm-hmm” feeling that this was her moment to contribute.

“Now, how do we do that, find our true selves through our agonies?” Leonardo continued, now appearing to address some invisible entity hovering above the coffee table. A ghost, or God, or something magnificent and imposing. Whatever it was, it was clearly wonderful to see and Claudia wondered at his vision. He went on, “how do we act like ourselves when we supposedly always are ourselves? Well, aren’t we?” Now, he slowly lowered his gaze to the tightrope walk of the plate on his knee. “Maybe we realize that we are our sickness as much as we are our health. Those tragedies of the body are also a part of nature, which isn’t one experience but an infinite number…an infinite number of experiences.”

He seemed transfixed by the brown frosting swirls, which quite pleased Claudia’s mother and she smiled at what looked to her like man finding his muse. Not the case, of course, but what a wonderful scene! she thought. Leonardo’s voice became a bit quieter, as if he was speaking to himself. “What would it be to see not a distinct tree, rock, or droplet of rain, but the same essential elements that compose one’s own body? What would it be to know oneself as a fundamental particle of nature’s infinity?”

Marta turned to braid the other side of her head, now looking directly at Leonardo but not actually seeing him—the twisting activity barring this whole speech from her mind. Claudia’s father nodded to himself, having figured out how to end the game in three moves. Now he listened.

“One cannot quite call the moments of our lives “scenes,”” said Leonardo with the hint of a chuckle, “even though we would like to believe in some continuity of the states of our bodies and minds such that we may retell our days as a single, wonderful story. But the moments of our existence cannot be called scenes since they always escape the categories we try to give them. If they are not “scenes” then perhaps they are flashes, decomposing flashes, which hold the same force that both sustains and destroys; our beings are not a directed wind but air as it breathes and becomes in and around us.” He stuck a tiny fork in his cake and took a massive, and surprisingly quick and spirited bite.

Was this man a doctor? thought Claudia. She looked at his hands which were beautifully sculpted, had the elegance of one who can hold certain instruments with great and natural ease, but his fingernails were black. People listened to his speech no differently than to Marta complaining about a pimple, which was both astonishing and unsurprising to Claudia. The family mind took a misunderstood note or two from Leonardo and began with a whole new set of theories, then transitioned to other unrelated stories, the workdays of tomorrow, the weather, until it was time for goodbyes.

One by one the guests departed—Leonardo thanking Claudia’s mother for the cake very sweetly—until it was just Claudia, her parents, and her grandmother who offered to drive her home on her way to drop off some cake for Oscar, one of Claudia’s older cousins, who hadn’t been able to get out of work today. Claudia hugged her parents goodbye, feeling some great softness in her mother’s back when she embraced her.

Claudia looked at her mother strangely, saying “who is this Leonardo guy?”

“He moved in down the street a few weeks ago, and, poor thing, his cat just died.”

“And what does he do?”

“He’s a zoologist, or, he studies the decomposition of animals.”

“The decomposition of animals?”

“Yes, I visited his lab once, it’s actually quite close to your house, and he showed me this horrible disgusting rotting seal and spoke about the thing for thirty minutes in incredible poetry, it was completely bizarre.”

This story was adapted from a final piece for the course Medical Ethics