Walking around our college’s neighborhood, I find myself trying to trace a history through the different styles of architecture. Whether you stop to glance at the stoic church next to our administration building, or the newly constructed apartment buildings on the way to the supermarket slowly filling up, it is clear that Pankow holds a plurality of experiences, and has undergone many architectural and historical phases. An article by professor Aya Soika on the Bard College Berlin website provides a brief history of the campus starting from the mid 20th century, detailing that the buildings currently in use by the college were once embassies, consulates, and residences in the diplomatic quarter of East Berlin. Reading this piece led me to wonder further about Pankow, about the other identities it has held. Having taken a class with Aya last year about memorial culture in Germany, I decided to reach out to her and inquire further about Pankow’s architectural history. She was generous enough to lend me some of her time for a quick chat to answer some questions.

Can you talk about the different kinds of architecture one sees walking around Pankow?

“Pankow” itself consists of many different districts, the northern ones are on the margin of the city, others have a more urban feel to them, with cafés and shops such as on Florastrasse. If you take the M1 in the direction of Rosenthal Nord you get a good sense of what it means to be in the former East part of Berlin – the “Randbezirke” in former West-Berlin are much more densely built up. Space was limited in Rudow or Lichtenrade in the south, and every square metre was used within the concrete walls of the city. Not so in the north of Pankow where it’s not far to the fields such as the Zingerwiesen near BCB or the meadows nearby the Botanical “Volkspark” Pankow-Blankenfelde. If you want to go for a long walk I recommend the Pankeweg along the river Panke. This is how the district got its name, by the way.

I love going to the botanical park! This makes me wonder, when did the construction of buildings in the style of architecture that we see in Pankow today begin?

Berlin as we know it today was only formed in 1920—until then today’s administrative district of Pankow was not part of the city, but belonged to several more rural outskirts. At the turn of the century there were still a few beer gardens near Platanenstrasse, for city dwellers to come out for the weekend. The area around Pastor-Niemöller-Platz, which is one stop from the campus’ main administrative building, wasn’t exactly rural back then, but it wasn’t very urban either. Some of the housing you see around Bard College Berlin dates back to the late 1800s, the decades which saw rapid population growth and the extensive construction of four-storey apartment blocks such as those on Treskowstraße, where one of BCB residential Halls is located, or the elegant houses opposite the Rewe supermarket on Waldstraße. The red brick stone church next to our administration building was constructed in Expressionist style in the late 1920s. If you are looking for real sights in the neighbourhood—I would say check it out, it has a really interesting history. The other nearby place that’s easily overlooked is the Soviet memorial at the very end of Platanenstraße.

Speaking of Platanenstraße, what can you say about the history of our campus buildings specifically? You talk a bit about their style in connection to Bauhaus in your article on the college website.

The flat roof bungalow structures which house our administration offices and seminar rooms might remind you of modernist 1920s buildings in the style of the Bauhaus School of Art and Design, but in fact they were only constructed in the later 1970s when Pankow was transformed into East Germany’s diplomatic quarter. All of them share the same ground plan and materiality. In fact, if you go for a walk around the neighbourhood you’ll find many more houses of this type, most of them have been turned into family housing. If you want to learn more about the function of our buildings during GDR times you can check out the article on our college website where I have tried to sum up how the different BCB buildings were once used until after the fall of the Berlin wall.

What else can you say about how Pankow’s architecture differs from other areas of Berlin?

Pankow is as heterogeneous as most other areas in Berlin; you find old structures next to brand new buildings, a very eclectic range of family housing with gardens as well as the typical turn-of-the century apartment blocks including some interesting social reform projects such as the Paul-Francke Housing Estate of 1908/09. You should also check out the ellipse-shaped street called Majakowskiring with houses which accommodated many senior figures of the East German government, shielded from the rest of the population. It’s not least due to this that Pankow became a synonym for the GDR government and its privileges. And last but not least, there’s the Palace of Schönhausen and its park. It was here where the Nazi Propaganda Mininstry kept some of the modern paintings and sculptures that were confiscated as so-called “degenerate art” from public collections.

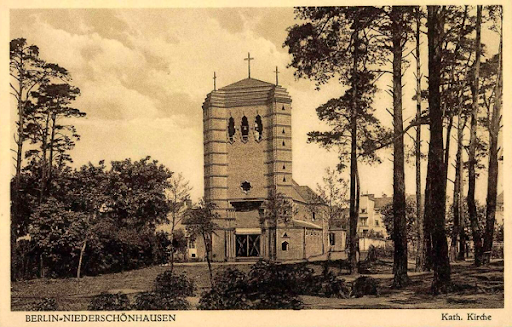

After our conversation, Aya sent me some vintage photographs of the areas of Pankow that we’d discussed, and suggested that I take some images of Pankow today to visually witness the differences in the composition of the neighborhood. Thus, I spent a sunny Saturday strolling around, experiencing a feeling of awe as I realized that in a strange way, not much has changed. On my endless walks in Pankow, I often think about the figure of the Flâneur, a person for whom, as Walter Benjamin once wrote, “the street becomes a dwelling… as much at home among the facades of houses as a citizen is in his four walls.” The Flâneur is a detached observer, a witness to modern, urban life. This figure often resonates with me—as a resident of Pankow I remain at a distance due to linguistic and cultural barriers, yet, I still bear witness to the changes in the neighborhood, and feel attached to the community, even from afar. Interviewing Aya pointed me towards new patterns and intricacies in the neighborhood. Strolling down a street on the outskirts of Niederschönhausen, I saw a family home in the exact same design as our classroom buildings. I noticed how modern life had largely left Treskowstraße untouched. While Pankow has certainly modernized, it is also largely left architecturally unchanged from even 100 years ago.

Slide between the images to see the way things have changed!

A postcard of the street across from our local supermarket and the building today (without it’s spires!).

A postcard portraying the church next to our administration building and the church today.

A postcard captioned “Greetings from Niederschönhausen. Restaurant and concert garden from Carl Liedemit” and the lot today.

Aya’s article on the college’s website ends with a section about “redefinitions” of our campus buildings in contemporary life. While this was a description specific to Bard’s reuse of old embassies on Platanenstraße and Kuckhoffstraße, I feel as though it can be seen as a greater reflection of the neighborhood of Niederschönhausen. The apartment building across the street from the supermarket still stands, but has lost its spires. The restaurant on Treskowstraße is gone, but empty space remains. Even the church has gained neighbors, including students rushing to class in our buildings just a few paces away. Talking to Aya gave me a newfound appreciation for the cycle of changes in Pankow, and made me feel closer to the neighborhood, and the community that we are a part of.