On November 6th, Florida overwhelmingly voted in favor of Amendment 4, with 64.5% giving back the right to vote to 1.4 million Floridians with nonviolent felony charges – a constitutional right that had been revoked at the moment of a criminal charge or imprisonment. It was the biggest restoration of the right to vote to a group of Americans since (white) women got the right to vote a century ago. Just by passing this Amendment, Florida’s voters rejected one of the main functions of the American prison system in their state i.e. its ability to take away voting rights from prisoners and even people who have been charged with a felony but never went to jail for it. They found it unjust that people who have made mistakes or were perhaps forced to commit a felony out of desperation or coercion in the past should be barred from voting for life, so they changed the law in the most democratic way possible: through referendum.

I did not follow the Amendment 4 campaign closely until about a week before it was supposed to pass. However, right after the amendment passed I did watch a truly heartwarming Democracy Now! interview with the president of the Florida Right Restoration Coalition, Desmond Meade, who spearheaded the Amendment 4 campaign. Democracy Now! reported that: “One in five African Americans in Florida and more than 10 percent of Florida’s adult population were ineligible to vote in Florida’s 2018 election that happened [on November 6th] because of a criminal record.” Mr. Meade, who is himself an ex-offender, looked ecstatic as he spoke about what he called “a historic victory.” He beautifully said:

I am tired. But I am excited, because, you know, I think we had something special happen last night. And I think a lot of folks are not really grasping it right now, but eventually they will really understand that what we’ve seen in Florida was love prevailing. Just that simple. Love prevailed. We had over 5 million votes for Amendment 4. And those were votes of love, people voting for their loved ones and friends who made mistakes and paid their debt and wanted to move on with their lives.

It was because of the love that Mr. Meade spoke about that Floridians questioned the justice of prisons. Like other acts that have given the right to vote to a previously disenfranchised group, such as women or the black community, passing an amendment like this into law questions the very logic of the system which deprived a group of a right that should be guaranteed. The counter arguments made against women’s and black people’s suffrage in relation to these groups’ “over-emotionality” or “lack of intelligence” are based on hate and uninformed bigotry — they are not grounded in reality. But systems of oppression certainly have an internal logic that benefits a dominant group. It made sense for the propertied white men to bar women and black people from the democratic process because it would shake up the status quo in which they held (and still hold) most of the political and economic power.

To question and challenge those established systems of oppression takes courage and a sense of morality. It takes love for your fellow people and the willingness to forgive them for making mistakes. It takes faith that a community can heal without the threat of lifelong punishment and democratic exclusion. Perhaps the love that Mr. Meade is talking about can extend to an even greater idea. Perhaps that love can get us to imagine a world in which forgiveness and healing happen without the presence of cages. Some scholars, activists, and (ex)prisoners call this prison abolition.

Sadly, most politicians talk only of prison reform without questioning the existence of the prison system. However, it is extremely encouraging that outlets like The Guardian or Politico have started publishing articles on the topic of prison abolition: if it is being written about in mainstream media, perhaps it is not simply an ideal that can never be achieved. Indeed, there are steps in the form of policy that we can take in order to get there one day. The reason why the idea of prison abolition has not become a mainstream political position — although many DSA (Democratic Socialists of America) chapters support the idea — is that, in a lot of people’s minds, the idea of justice is still equated with the state criminal justice system. Though it is easy to name historic examples of laws that have been unjust, such as Apartheid or the legality of slavery, many people did not perceive them to be so when these laws were upheld. It is also much easier to condemn the past, but not so easy to shake the notion that perhaps the criminal justice system as it exists today is unjust as a whole. Thus, it is easier for people to see it as “broken” or “in need of reform” rather than as a system that was purposefully set up to affect primarily African-Americans as well as other communities of color, immigrants, and poor people, as I will explain below.

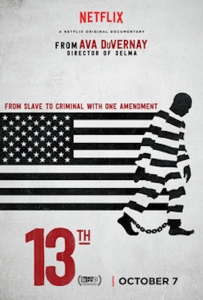

In her documentary 13th, [*1] award-winning director Ava DuVernay traces the links between slavery, inmate leasing, Jim Crow, the Civil Rights Movement, the war on drugs in the 70s and 80s, and the development of what we today call the “prison industrial complex”. I highly recommend watching the documentary in order to get a grasp of the long and complicated history of the American prison system. But, to briefly summarise, race has always been tied to the creation and maintenance of the American prison system. Even though the U.S. Constitution abolished slavery in 1865 with the 13th Amendment, it left a loophole that has been exploited by American prisons and capital (i.e. the state and the private sector) since: No person can be a slave in the United States unless he or she has been convicted of a crime. Thus, slavery was not fully abolished in the U.S.; it merely changed its form. When slave owners couldn’t rely on free labor anymore, the state started arresting large numbers of freed African-Americans for petty crimes, like loitering, and branded them criminals. This gave birth to the prisoner leasing system that re-enslaved a large number of black Americans in the South. This system has changed its form time and time again resulting in big companies, like Victoria’s Secret and Whole Foods, nowadays often signing contracts with both public and private prisons to produce their goods there with labor as cheap as 0.20 cents an hour.

13th, as well as popular TV shows like Orange is the New Black, have done a great job of informing the public about the history and the horrors of the prison system. Of course, political movements such as Black Lives Matter have also spoken about the prison system in relation to police brutality, racism and racial justice. Had Floridians been asked this question a decade ago, the outcome might have been very different. 13th, along with books like Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, made sense of the history of the US carceral state while Black Lives Matter has brought attention to how black men (and women) are disproportionately targeted by police and how that racial profiling has led to a disproportionate number of incarcerated black folk. On the pop culture plane, Netflix’s Orange is the New Black with its fictional Litchfield Correctional Facility has humanized incarcerated women, who are even more absent from the public imagination than male prisoners. The show doesn’t reduce its protagonists and side characters to mere “criminals.” In fact, most of the characters’ backstories are told through flashbacks, showing that they are full human beings with interests, dreams, and loved ones, who happened to have made mistakes that led to their incarceration. In recent years, the logic behind America’s carceral state has become clearer to the American (and international) public.

To do nothing to alleviate the suffering of communities that have been systematically disadvantaged through police-prison mechanisms in this way is cruel and simply makes no sense. When presented with the facts, many people see that it is unethical and therefore cast a vote not on the basis of personal gain, but on the basis of almost universal morality. Perhaps to the voters of Florida, Amendment 4 just seemed like a common-sense reform. I would, however, argue that Floridians have voted for something much more radical: They have voted for a prison abolitionist reform. Amendment 4 undermines one of the primary functions of the U.S. prison system, and that is way more revolutionary than simply improving prison conditions. On the 6th of November, in the swing state of Florida, the balance of power changed: and, as Mr. Meade suggests, that change may have been prompted by love that is truly radical.

Still, most of the voters in favor of Amendment 4 probably do not identify as prison abolitionists. Imagining that certain reforms, such the decriminalization of marijuana, can be passed in order to lower some prison populations seems more doable than getting rid of prisons altogether, leading many to see prison abolition as an unachievable dream.

In Are Prisons Obsolete? [*2] Angela Davis writes:

Many people are familiar with the campaign to abolish the death penalty. In fact, it has already been abolished in most countries. (…) Few people find life without the death penalty difficult to imagine. On the other hand, the prison is considered an inevitable and permanent feature of our social lives. Most people are quite surprised to hear that the prison abolition movement also has a long history — one that dates back to the historical appearance of the prison as the main form of punishment. (9)

It is important to remember that institutions that people have built are not natural. They have come about as a result of historical events and have been constructed by humans. Prisons as an institutional structure should be questioned in order to assess the kind of harm they are doing and in order to think about what justice means for us as a society. So, rather than talking about imprisonment as the only way of serving justice, we should be — and have been — questioning the justice of prisons themselves.

When we start radically rethinking our justice system, usually two questions come up: 1) in the absence of prisons, what would we do with murderers and rapists? And 2) what do we replace prisons with? Unfortunately, I and many prison abolitionists do not have completely satisfying answers to those questions, but I do have a response.

The first question is not that interesting to me and honestly not that significant because most people affected by the prison system and most “criminals” are not murderers and rapists. To keep a system that has historically harmed the African-American community in particular so much and that is now starting to disproportionately affect immigrants around simply to contain and punish the small minority of people that commit very violent crimes seems to do more harm than good to society overall.

The second question I would like to answer by quoting the unlikely person that sold me on the concept of prison abolition about a year ago. I was watching a lecture/dialogue between Angela Davis and Judith Butler when a young girl named Alia Moore asked Davis “How can we close prisons?” To this Angela Davis says: “That’s a great question. (…) I don’t have the answer, but I am part of an ever larger group of people who really wants to make sure that prisons do not represent our future.”

Angela Davis tells Alia about the concept of decarceration, which is the opposite of incarceration and which she defines as “taking people out of prison.” Then Davis makes one of the ultimate claims about the subject: “Prison abolition represents much more than just getting people out of prisons. What’s more important is to try to create a society that doesn’t need prisons.”

“So tell me: what do you think we need?” Davis asks Alia after the audience applauds her explanation.

“Schools?” Alia tries to guess.

“Schools, absolutely. Schools, not prisons!” exclaims Davis. “You see, we can talk about healthcare and housing and all of these things, and that is precisely what it means to try and get rid of prisons.”

And that is why prison abolition is such a radical idea. There is no easy fix to the prison problem because prisons are symptoms of larger social, political and economic issues of institutionalized (economic) racism and poverty. So the driving motive behind prison abolition is not just to decrease the prison population: rather, it is to radically transform our society in such a way that prisons are no longer necessary. A large amount of criminal acts are committed as a result of poverty or as a result of aggressive socialized behaviors: for example, a homeless person may steal in order to eat that day, and toxic masculinity compels men to get into violent situations or commit intimate partner violence.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. We can build a society in which the state doesn’t racially profile black and brown men as inherently dangerous, in which we do not teach young boys that manhood means violence, in which safety nets exist and poverty doesn’t. If we can build a society like that, then, to answer Angela Davis’ question, prisons will be obsolete.

—

Notes:

[*1] 13th. Directed by Ava DuVernay. 2006, Netflix.

[*2] Angela Y. Davis. Are Prisons Obsolete? New York: Seven Stories Press. 2003. Print.