On March 11th, a sunny Sunday afternoon, the participants in the course An Intellectual History of Feminist Thought went on an excursion to the Schwules Museum: Berlin’s unique museum depicting gay life. As it was made part of our yearly Berlin programme, other ECLA students were also given the opportunity to sign up and join Ryan Plumley and his students for a tour.

Founded in 1987, this—literally—Gay Museum (given that the term “schwules” in its name is indeed used as an adjective) contains a permanent exhibition focused on the history of mainly male homosexuals in Berlin, beginning in the late eighteenth century.

The project came into existence when a group of gay students from the Freie Universität, who worked in the Berlin Museum on a part-time basis, had the idea of installing a temporary exhibition on gay life there. To everyone’s surprise, the then director immediately agreed, and in order to attract a broader public, the decision was made to include in the temporary exhibition a history of lesbian love.

Taking place in 1984, this exhibition, titled Eldorado – Geschichte, Alltag und Kultur Homosexueller Frauen und Männer in Berlin 1850-1950 (Eldorado – History, Daily Life and Culture of Homosexual Women and Men in Berlin 1850-1950), was both the most controversial and the most sensational display the city had ever seen.

Given its success, it was soon decided that the exhibition should be made permanent, and a space for it was found at Friedrichstraße. It was at this point that, for more or less mysterious reasons, the focus of the museum was again put on male homosexual life only, leaving out many of the aspects of lesbian culture the temporary exhibition had incorporated.

Subsequently, the Vereins der Freunde eines Schwulen Museums in Berlin e.V., or the “association of friends of a gay museum in Berlin” was founded by the same group that had called the temporary exhibit into existence the year before.

Soon, an archive and a library were installed, and it was in 1988 that the museum moved to Mehringdamm in Kreuzberg, where it is still situated. Along with its permanent exhibition, the museum mounts temporary exhibitions as well; at the moment, one on the movie director Pier Paolo Pasolini and one on the German actor Harry Raymon.

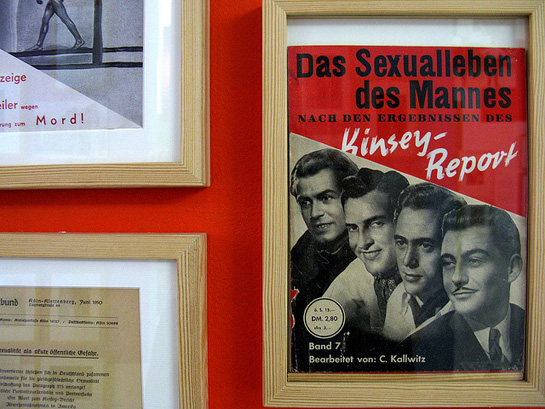

For the sake of our tour, we spent most of our time in the permanent exhibition on the upper floor. It shows a history of gay life in Berlin over a time span of 200 years—from 1790 to 1990. As the earlier history is one especially shaped by repression, punishment and persecution, the Schwules Museum made it its task to put a special focus on the persistence and self-confidence of the gay community that arose out of these circumstances and it underlines its observations with an exhaustive amount of—mostly written—evidence.

It shows how homosexual networks already began to appear in European metropolises in the seventeenth century and how the acceptance of homosexuality reached a high in the Weimar Republic, and was then aggressively suppressed again during the Third Reich.

Finally, it gave us an idea about how the 1960s and the Flower Power movement brought significant changes in the direction of a positive acceptance of gays within society once more. The exhibition also includes interesting information related to the fall of the wall, despite the fact that it is in general a more West Berlin-centred exhibit.

Even though there were many artworks to examine, the actual historical information—of which there was a lot—was unfortunately only provided in German, which required the non-German speakers in our group—of which there also were a lot—to read the descriptions and all the content from booklets.

Apart from this, it was a very interesting and unique experience, where we learned much about the topic most of us had not been confronted with to such an extent before. Doing justice to the theme of the day, our small group later made itself comfortable in a night-time-gay-club, day-time-café just around the corner from the Schwules Museum, to both discuss what we had seen, and enjoy the weekend together.

by Johanna Fürst (AY’12, Austria)