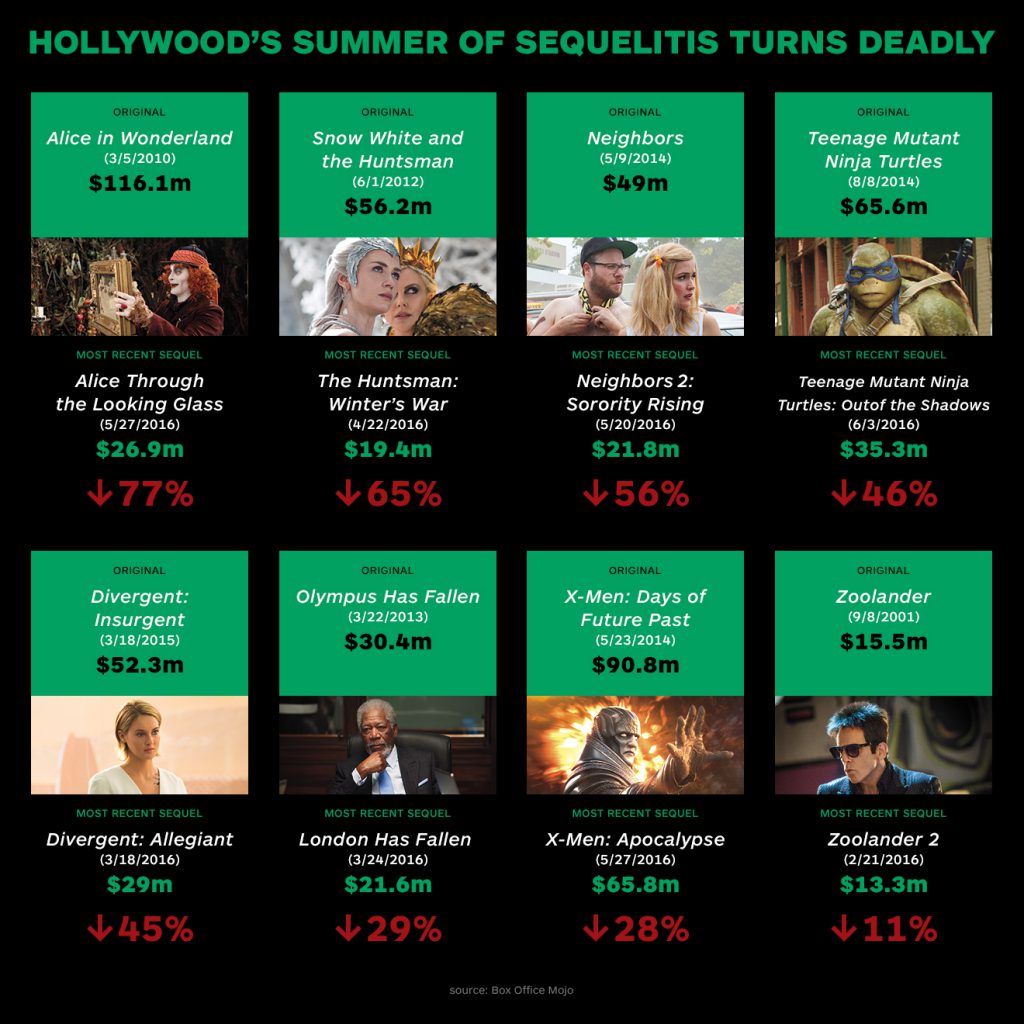

2016 has been a historically awful year for Hollywood. Cinemas have not sold this few tickets per person in the US since the Great Depression. Meanwhile, sequels have become Hollywood’s new addiction.The number of sequels among the top-grossing Hollywood movies has doubled in the past 10 years. At the same time, we see that several sequels failed at the box office this year while Marvel movies are still living up to their usual numbers.

Could this signal the decline of the long-standing sequel strategy?

Sequels are not new:

Although the general observation that most movies before the 2000s were typically standalone ones is not unjustified, sequels and other recycled material have been a safe and common strategy for Hollywood from its inception. The 1930s was not only the decade when the horror genre established foundations in Hollywood, but this era also created constant recycling of familiar characters such as Dracula, Frankenstein, the Mummy and the Invisible Man that became so popular that Hollywood decided to follow up on them with sequels. These films may have just launched the first franchises in movie history in the sense that they featured recurring characters and kept a fairly consistent world and style. It is also important to point out that these characters were not original Hollywood inventions themselves but were mostly adaptations of literary characters: See Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus (1818); Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897); H.G. Wells’ The Invisible Man (1897). Shockingly, we can even see examples of sequels dating back to the very beginnings of commercial cinema. The first ever movie remake was George Melies’ Une Partie de Cartes (1896) which was a parody of the Lumiere brothers’ Partie de Cartes from the same year. Melies’ Voyage á traverse l’impossible (1904), which chronicles a space trip into the sun, is also among the first sequels. It follows his classic genre-defining Le voyage dans la lune (1902). The first remake was Edwin S. Porter’s parody of his own pioneering western The Great Train Robbery (1903), ironically named The Little Train Robbery (1904).

Cinema has lost its old cool:

Our stereotypical idea of the cinema as a glorious temple of audiovisual magic with neon lights, the inviting scent of buttered popcorn and the red carpet on premiere nights now belongs to our mental wax museum. In the ‘50s, with the rise of the rebellious youth of the baby boom generation and the blooming of cursing culture that we can see in George Lucas’ nostalgia masterpiece, American Graffiti (1973), the cinema was the number one date-location. It adopted an aura of sexuality and individuality as teens got away from the dullness of family life, got into their ’55 Chevy to pick up their “sweetheart” and drove to the cinema. This exaggerated picture of the era illustrates what mental image we might have of this time, in which the cinema was a sacred place of rebellion and sexuality.

This dream of the cinema is lost in time. Today we often think about it as a graveyard of commercial waste, a place stripped from its aura with its primary purpose being to convince us that it is a good idea to buy that giant menu of nachos because why not. Going to the cinema is a rare occasion anyways. Having said that, that’s of course not all we have in mind.

Producing films became much more risky:

In our days, going to the cinema became sort of like a check up for cultural well-being. Aside from the usual moviegoers, visiting the cinema became a special occasion, much like going to the opera or the theatre. US moviegoers visit film theatres four times a year on average which is a devastating number for Hollywood, considering that in the ‘50s, this was done weekly. In this desperate situation, Hollywood has an extremely hard time gathering an audience for each film. It only makes financial sense to produce less films that are huge in spectacle and budget than to produce more smaller films that can take creative risks because they are toying with less money. It also follows that studios will spend proportionately more money on advertisements than before since it has became much harder to grab people’s attention. In 1980, the industry spent 20% of the ticket price on advertising. This number grew to 60% by 2016.

Films in the ‘50s were stable investments. Besides television (which also proved to be a vicious competitor) cinema was the dominant source of entertainment for the masses. Since the studios could count on stable revenues, it was more common to take on risky and minor side projects. A good script, a promising director, an exciting theme or even a title alone proved to be an often profitable experiment. A prominent example of title and theme-driven low budget filmmaking in the ‘60s was producer Roger Corman’s enterprise that created an immense number of low budget B-movies and allowed such young film students like Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, James Cameron and Ron Howard to launch their careers.

Films need to be globally understood:

Since the market in the US seems to be shrinking, Hollywood sought to expand overseas. Between 2009 and 2011 the US/Canadian box office revenues grew by slightly more than 2% while the international market grew by 27%. This can be attributed to the fact that, while US audiences generally grow tired of sequels, overseas they remain immensely popular. This is why, although the last few Pirates of the Caribbean flicks slowly faded at the domestic Box Office, there is still a demand overseas to produce a 6th movie. Films need to be internationally marketable products that appeal to consumers everywhere, no matter their cultural/ideological background. Therefore, specific, culturally contextualized themes are abandoned or only kept in subtlety. Specific humor, political commentary, complicated characters and obscure plot elements are avoided in favor of universality. The commodified language of cinema becomes spectacle and a schematized plot simplified to the core.

Online media outlets (Netflix, Hulu, Youtube, Facebook) took over:

Cinema in contemporary society found some new, dangerous competitors. Most of our communication and entertainment is now mobile and belongs to online platforms. Most forms of entertainment cater to the individual wants of the consumer. It is the consumer who is in the center of production as we choose when, how and what we consume, and the market responds to our demands quicker than ever. The movie watching experience has been transformed entirely. We do not need the screening guy anymore to change the film roll from one to two. Instead, the movies are coming with us wherever we go and can be started, paused, sped up, and rewound as we wish. The newest shift on this technological trajectory is Netflix and other streaming sites that popularized and further reinforced the binge watching experience in which we see movies one after another based on our personal preferences. If you watch a lot of superhero movies, your feed on Netflix will push you to watch even more. No wonder that sequels, reboots, remakes and other exercises in intertextuality — that is, the relation of one or more films to each other, like the Harry Potter series to the upcoming film Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2016) — are so common. Intertextuality is key to economic success.

Movies are made for kids:

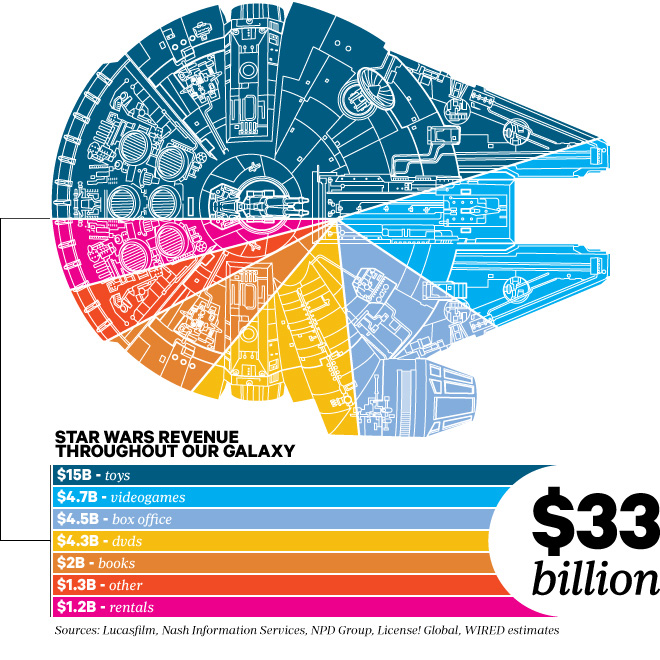

Since Star Wars (1977), franchises like Marvel have become the dominant form of big-budget film production. Franchises are cinematic enterprises that create fictional worlds that seem strangely familiar to us as they expand in detail and gravitas with each sequel, novel, video game, comic or fan-made literature. Toys and other merchandise are the main source of revenue from franchises. (Refer to chart). Consequently, children from 8-17 became an essential target audience. Kids are the most vulnerable consumers. They are easy to condition to love films and they never come alone to the cinema; they bring their entire families with them. It follows that mainstream films are progressively becoming more child-friendly, only occasionally tipping into adult territory in order to ease the boredom of parents. No wonder that the Star Wars franchise under Disney is also becoming more child-oriented. The element of sexuality between characters, like the love triangle between Han, Luke and Leia, and graphic violence are pushed to the background in favor of the Disney-style friendliness and cuteness (BB8, Finn).

The Renaissance of originality?

The current sequel fatigue may not automatically mean that sequels and other recycled material are finished. Indeed, they deserve their place in cinema and have been out there from the beginning. Many of the greatest achievements in popular cinema were made possible by franchises, reboots, remakes etc. The list is endless. Think of the Star Wars trilogy (1977-), The Godfather series (1972-90), Scarface (1983) and the Indiana Jones movies (1981-).

However, it is important to note that these franchises often came from humble beginnings, made on relatively low budgets (A New Hope was made on a paltry 13M and The Force Awakens on 306M), and that creators took immense risks to create something new. Few expected the success of Star Wars or the Godfather, and none were aware that they would grow into major franchises.

In a late 2015 interview made by veteran talk show host Charlie Rose, George Lucas talks about the change in the industry that Star Wars brought with it: “Well, it changed for the good and for the bad. When you bring new things into a society, you can either use them for good, or you can use them for evil. And what happens when there is something new, people have a tendency to overdo it. They abuse it.” He goes on and clarifies that he means that the spectacle element of those movies got way more attention than the substance and the mythology that stood at the core of them. In contemporary cinema we have grown accustomed to this, and we have become extremely forgiving. People forgave The Force Awakens (2015) for not coming up with a new story. The commonly held view was that it had to cater to so many of the fans’ expectations that there was almost no room for originality. But is it really the main objective for movies to only fulfill our expectations as fans and consumers of our own nostalgia? As we have seen, Hollywood has became extremely commodified, catering to the presupposed needs of target audiences. It might be their responsibility to surpass and even contradict our expectations, but it is ours to not settle for less than we deserve.

[hupso_hide]