After spending week three deliberating on various part of the Bible for the AY/BA1 core course on Forms of Love, we waded deeper into the ocean of Christian ideals by reading St. Augustine’s Confessions. Acting as an intellectual lifeguard of sorts, Johannes Zachhuber was our guest lecturer for Monday. He studied theology in Rostock, Berlin and at Oxford, where he received his doctorate. He then went on to teach at Humboldt University before taking up his current position at Trinity College, Dublin.

The first question Dr. Zachhuber asked was about why we talk about the history of love and why we suppose that love should have a history at all. It would seem more appropriate for things less abstract like a people or a country to have histories. However, one way of looking at history is to regard it in the light of a genealogy of ideas. Things like freedom, power, and love only exist insofar as people continue to have ideas about them. It cannot be disregarded that there is a subtle interaction between the reality of a phenomenon and paradigms people attach to it and thus, the lecturer reminded us, it is important to remember that St. Augustine’s society affected where he decided to look for love.

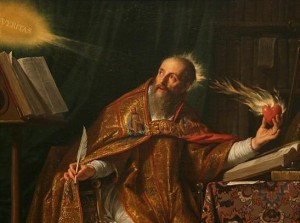

The reason why Augustine is central to an understanding of Christianity is because he is a theologian who reflected on the massive change in Christianity to the point that his ideas became quite dominant. The fundamental theme of his ruminations on the subject was that love’s desire for what attracts it is what deserves to be loved. The supreme good is ultimately God and God should therefore love his own being without heeding humankind’s needs.

One could say though, that the love of the New Testament is different from Greek Eros. There has been speculation that this is a perverse idea because love always will be desire and once you desire what’s superior, desiring that which is weaker is not that far behind (and this can be seen in the larger concept of God loving the world).

People who argue against Christianity usually see this quality of being able to love as human conflicting with the idea of God as being a self-sufficient and unalterable being. Conversely a defense of Christianity states that Christian love is not Eros but is about a person who possesses some good and out of their own abundance decides to share it with others.

It now makes sense that God should out of the fullness of his being want to give away part of it. This desire to give without seeking reciprocation is the essence of agape. One must wonder if this kind of love ever becomes condescending in assuming the figurative king-subject shape. If so, the object of love must become insignificant and love does not remain any longer about giving.

An intriguing nuance of the subject was how erotic love played into the equation. The love of the New Testament seemed detached from sexuality and the only mention of it came in the Old Testament’s Song of Songs where the language of erotic love is applied to the relationship between God and mankind and then Jesus and the Church.

Dr. Zachhuber presented a few theses about love: First, that love is something we desire in itself and not as a means; second, that the fundamental structure of desire is present in all humans and that this desire will always seek the Good that is God (Desire though, has to be tended towards what is good or it will prove destructive.); third, that only what is the supreme good can be fully and justifiably loved and thus the only true love is for God. Things lower on the hierarchy like material goods should not be desired in themselves and only used but never loved.

The lecturer returned to St. Augustine and emphasized that his notion of love was essentially Platonic with two modifications. The first is that how we think of God when we desire Him is important. Augustine’s view of humanity as ‘fallen’ causes this intrinsic desire to become much more complicated because our true self is tangled up in a messy combination of beings which have been perverted by the Fall.

The second is that the will is influenced by forces other than the intellect so that when we agree to something, we may not necessarily want it. Augustine is largely responsible for highlighting the tension between sexuality and Christianity. Sexuality is singled out at the area where desire is the most ambiguous and the Self at the peak of conflict.

The lecturer proceeded to point out that Augustine’s concept of love was criticized for being too other-worldly. Hannah Arendt, for instance, posits that the idea of all love as love for God becomes detached from social necessities and directs love away practicality. There must be some kind of love for a neighbor without it being a reflection of God.

Dr. Zachhuber then concluded on a thought-provoking note by asking us to think of Augustine as someone who might help us contemplate love in a time when the highest salary and prettiest clothes make the value of life when ultimately that may not be the kind of life one might want to live. Conducted in a manner that was wonderfully intellectual and witty, the lecture brightened our Monday morning by framing the discussions we would have for the rest of the week holistically and informatively. We hope to see Dr. Zachhuber make a return to ECLA again!