Brassaï is the pseudonym of Hungarian artist Gyula Halász, whose exhibition we visited last week at Martin Gropius Bau as part of the Seeing Berlin programme. A notable feature of the exhibition is that the hanging arrangement of the 1950’s Moma exhibition in New York is now reproduced in Berlin.

Our guide began the tour from the last room of the exhibition, where Brassaï’s common motifs: love, sexuality and death, were most evident. We were shocked to learn that Brassaï did not create graffiti himself, but instead photographed graffiti sites. He used to keep track of them in a notebook and always returned to the ones he shot to see what had changed. Uninterested in political graffiti, his black and white photos of carved trees and painted walls are focused on recurrent symbols, such as heart-shapes, masks, skulls, male figures and representations of the female body.

Brassaï began to experiment with photography in 1925. While working as a journalist in Paris, he decided to take pictures for the articles himself. One of his innovations is the concept of ‘involuntary sculpture’ in which different meaningless objects take unexpected forms when photographed from certain angles. Examples include photos of potatoes resembling spiders or a ticket changing shape when rolled up in someone’s pocket. Brassaï always denied working as a surrealist, mostly because he disliked the indoctrination of Andre Breton, but his involuntary sculptures and his work with Dali provide evidence to the contrary. His interest in the female nude is also innovative. Through the surrealist rendering of his photographs, the eroticism of the female body is replaced by a sense of beauty and platonic fascination.

His pebble stone sculptures are also somewhat surrealist, as Brassaï gently intervened in the shape of stones to bring out the object within – bird, female figure or male genitals. Under the influence of Picasso, he painted on already exposed glass negatives and then re-photographed them obtaining completely new abstract photos. Another of his practices was to interfere with the exposed photographs by cutting them to fit the chosen frame. This preoccupation shows Brassaï’s avoidance of conventional angles and compositions as well as his awareness of the role of art in photography. For the same reasons, he never allowed that his pictures be reproduced or anyone to assist him in the developing process.

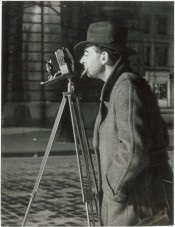

He was called the ‘eye of Paris’ for his night pictures of criminals and prostitutes on the street and in brothels. The people he photographed had to sit still for several minutes for a night photo to receive sufficient exposure. This required convincing his ‘models’ to collaborate and allow his assistant to light the scene with flashlights. Brassaï was actually the first to take such pictures by night, revealing the underground realities of Paris. He took pictures of couples kissing in public, a taboo at the time, and also a reportage series depicting Parisian events, all included in the book ‘The Secret Paris’. Apart from working as an artist and journalist, he also published 25 books, one of which is known for the dialogues with Picasso. His work in film-making was rewarded at the Cannes festival in 1956 (Tant qu’il aura des bêtes). On a lighter note, Brassaï is also known for measuring the necessary exposure time at night with the time it took to smoke one cigarette.

By Clara Sigheti (2007, Romania)