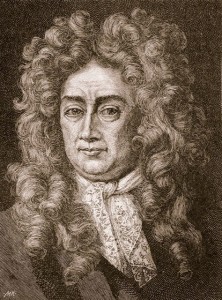

Students of the Property Core Course had the good fortune to have Professor Andreas Blank conduct a seminar about Samuel Pufendorf’s theory of necessity on May 30th.

Students of the Property Core Course had the good fortune to have Professor Andreas Blank conduct a seminar about Samuel Pufendorf’s theory of necessity on May 30th.

Professor Blank is a teacher of early modern philosophy in the University of Hamburg and his expertise was most helpful in comparing Pufendorf’s notions of ownership and necessity with English social contract theorists such as Thomas Hobbes and John Locke.

The 2nd year BA Core Course has so far covered different theories of property and themes that arise from political implications of property such as: slavery, money and sovereignty. The reading of Pufendorf comes when the course takes a turn towards necessity which was a prominent notion in the discussions of Giorgio Agamben’s State of Exception.

Professor Blank began a discussion of Pufendorf’s theory of ownership by introducing the concept of moral entities. Moral entities, as Pufendorf describes, are not found in nature and are at the same time dependent upon and imposed on human beings and their activities. The term ‘moral’ in this case does not necessarily come with ethical allusions and instead refers to a sense that these entities direct action.

Moral entities encase the relationship between human behavior and conventions, where some entities are bearers of moral qualities which regulate relations among persons (i.e. the state). Professor Blank offered the comparison of human beings and persons as an example, where human beings occur in nature, but the notion of ‘persons’ is constructed by a social and legal framework.

Pufendorf’s definition of ownership comes up against John Locke’s proposition that property rights are a natural right. Here, Prof. Blank provided a helpful distinction: whereas Locke views the relationship between man and his body as a right of dominion, Pufendorf sees the relationship as a right of usage, which does not immediately imply ownership. The law which grants exclusive ownership to persons does not underwrite absolute dominion and instead retains the capacity to disown private persons on grounds of necessity—the very notion behind eminent domain.

Necessity forms an exception to written law, where in practice, it could be taken as mitigating factor in cases of criminal activity, or as license to act in opposition to the letter of the law. Pufendorf’s interest lies in the notion of “imperfect obligation” where in times of extreme necessity, actions are beyond the reach of written law and instead derive their legitimacy from the “virtue of humanity.” By this, Pufendorf means that the action committed under circumstances of necessity is viewed as justifiable among men based on a sense of belonging to humanity or on an account of human nature.

Prof. Blank explained that, with respect to this notion, it is acceptable that a man in dire straits, who is refused help, can forcibly take from another whatever he needs for self-preservation. It is not a matter of seeking charity, since, based on the “virtue of humanity,” the fulfillment of this imperfect obligation is an act of justice and failure to conform to it is therefore a violation of justice.

Prof. Blank concluded with reference to a controversial claim which has often come to the forefront in recent times, and which emerged in our reading of Agamben with reference to detention regimes like the one in Guantanamo: the way in which the right of necessity is invoked constantly by governments wishing to act beyond the reach of law.

by April Matias (2nd year BA, Philippines)