I felt the chilly wind as I stepped out of the taxi. The hotel my boss booked for me was in the northern district of the city. I stood next to the car gazing at the dark red building while the driver took my suitcase out of the trunk. The building was wide rather than tall, built of old brick with most of its windows unlit even though it was almost sunset. Behind the hotel, tall, dark green trees. The large forest started here, where the noise of the city centre faded into the darkness among the trees. The driver handed me my small suitcase, bid me farewell, and swiftly drove away like he didn’t want to linger.

A winding path led me from the gate to the entrance. It was quiet and the sound my suitcase made was loud in my ears. Ever since the airport, I couldn’t shake off the feeling that people were watching me and pretending not to see me at the same time. It was as if people here didn’t acknowledge each other’s presence. I was used to being in busy cities as a news-seeking stranger, but there was something strange about this particular place, the way people averted their eyes from each other while walking restlessly. But it wasn’t without reason. The peculiar incident that was plaguing the city was the very reason I had been sent here in the first place.

I pushed the heavy, wooden door. Inside, the lobby was darker than I had expected. A woman stood behind the reception desk. In an elegant movement, her long fingers switched on the antique lamp on the desk. The orange light lit up the lobby and I could see her polite smile. She said, “Welcome to the Forest Hotel.”

I told her my name and she nodded, going through her desk. Over the counter, I could see a thick file full of forms. I guessed the woman was the owner of the hotel. She looked too old to be a mere receptionist, maybe in her sixties or seventies. “Is it busy here right now? It’s past the vacation season, isn’t it?” I said. Experience had told me people who work at hotels see and hear a lot of things: whispers, phone calls, and remarks from travellers who regard the hotel workers simply as passersby who will forget about them quickly enough. My job required that I collect information and I always valued what interactions with hotel workers. Besides knowing many languages, including the one spoken by the increasing immigrant population in this city, the ability to get close to people quickly had always made me fit to write gripping reports.

She looked up without stopping her busy hand and said, “Yes, although the strange occurrences seem to attract some people to this city.” “Occurrences?” She was right that I was here because of a peculiar incident. But the strange hole that had appeared at the northeast edge of the city was the only strange thing I was aware of, the only thing that might attract people. “Excuse me, the occurrence,” she corrected herself without losing her smile. She looked down again, found my reservation in her file, picked out a key from below the desk and handed it to me. “Your room is on the third floor, you can reach it with the elevator over there. Please use the phone in the room to contact the desk. I hope you enjoy your stay.” “Thank you,” I said, and headed to my room.

After putting my luggage in the room, I set out to investigate the hole. The sun had just set, but it wasn’t too dark to walk around yet. I had three days to write about the incident for the magazine which liked to include investigative pieces with little twists. The only thing I knew about the sinkhole was that it appeared with no apparent cause two days ago at the edge of the city, just between the residential area and the forest. The first report was given by some forestry workers, one of whom got injured almost falling into it. They said it was big enough to swallow a truck.

It didn’t look particularly out of place.The hole was on the side of the road, half buried in the forest. I guessed it was about twenty metres wide. I couldn’t see how deep it was, probably ten metres, even more. It looked as if a huge mole started digging into the soil and then changed its mind. Maybe the soil got loose. I didn’t know much about forestry but it seemed like something that could happen at a place like that. Would this make an intriguing enough story?

That idea was to talk to the witnesses, see if there was a good mystery here. That is, until I got a call from the hotel owner early the next morning. It was before sunrise and I picked up the receiver from the nightstand, still half asleep. Her voice just as clear and elegant as the evening before, she told me that another hole appeared, similar to the first one but closer to the centre of the city. Immediately I was fully awake and asked if she knew the location. She told me it was on the west side of the city. I thanked her, got ready, and hurried out of the hotel.

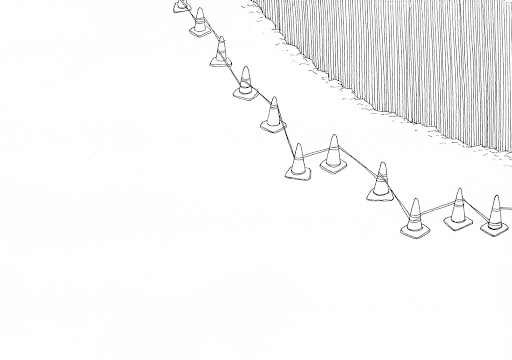

When I arrived at the scene, a crowd had already started to form around the area marked by red safety cones and yellow tape. It was at the intersection of two wide roads, tall buildings towering over on all sides. Police officers in uniform formed a smaller circle, busy with setting up more cones and a plastic cover in a muted tone of red. They are covering the hole, I thought. I stood behind the crowd. One of the officers walked over the tape and stood in front of it. He started to explain what they knew at that point, which wasn’t much, and I took out my notebook and quickly wrote it down. He returned to his colleagues and people began to leave.

A man standing next to me remained there, looking confused. From his clothes, I could tell he was an immigrant worker. I asked him in his language, “Shall I translate the message for you?” He became visibly relaxed. He nodded and I began translating. “A sinkhole appeared at the crossroad overnight. It’s about twenty metres wide and dangerous, so they are blocking the roads around it altogether.” The man nodded as I said this, but his face told me he was getting even more confused. “The police and the city are investigating the cause with the help of several scientists, but they don’t know much about it yet. They’ve asked that citizens be careful not to go into the area indicated unsafe with the safety cones and traffic signs.”

Now he was almost frowning. I was suddenly overtaken by the empty feeling that no matter how much I tried, this man would never believe me completely. The incident was too absurd. You could only take so much absurdity seriously, and it becomes even less believable when received from a stranger. He doubted me more than he doubted the police who had been explaining the situation in a language he didn’t fully understand. As I translated the words, I saw the confusion on his face turn into doubt. Doubt for the news, sure, but more than that, doubt of my translation. Or, maybe, suspicion towards my intentions in saying such absurd words to him. The suspicion was always going to be there since I was an in-between. It’s harder to believe someone who acts as if they know both sides.

I spent the whole day trying to interview people. Most were not particularly willing to answer questions from a stranger and avoided my gaze when I approached them. That in itself was not unusual; when I investigated strange occurrences people tended to either be extremely excited about them, eager to talk to any reporter, or be totally quiet, not wanting their daily lives to be disturbed further. This city was clearly the latter. But the frown on the immigrant worker’s face was stuck in my head and my uneasiness with this city grew.

It might have been the utter lack of expression on the faces on the street. There were office workers in neat clothes, the elderly, students, and there were the immigrants who I could recognise from their forestry workers’ clothes and haircuts different from the other residents. They were all different kinds of people, but besides their quick walks typical in big cities, their faces somehow looked similar, their gazes focused upon nothing in particular and giving the impression of emptiness. But maybe it was in my head.

Most of those whom I approached had heard about the holes in the news. But they did not seem to care. They did not even stop using the underground. They still rode them to get to work and school, and when I asked if they were not scared because of the incidents, they just shrugged and said, they still had to get to work, what would they do otherwise? That rationality scared me. Of course, none of the underground rail lines were close to the holes. But I thought there should have been more of a reaction to such a thing. Or maybe they didn’t see it as strange but just flaws in the construction of the particular roads on which the holes appeared. I didn’t know, and that made me feel chilly. I continued my investigative process, approaching people to ask questions and looking for what the local newspapers said, but as it started getting dark, I thought it better to get back and put together the beginning of the article. I started walking towards the bus stop. I didn’t feel like taking the underground to the hotel.

There was a bar at the end of the street. I decided to get a drink or two. I was tired. I pushed the heavy door and slipped in. It was dark but quite full with customers, all of whom halted their conversations and looked up as I entered. I paused, feeling as if I intruded on something, but they looked away from me and resumed talking after a second. I took a seat at the counter and ordered a beer. I sat there quietly and observed the people in the room. Here, I felt that people looked more ordinary and relaxed than when I saw them outside. Was it the assurance of being indoors? Walking outside, people were scared of the holes, perhaps. I tuned into the conversation of the two men next to me.

“No, but you’ve got to admit that it’s a neat place,” one said.

“Sure, it brings people to the northern district,” the other replied, laughing, “which is great, for our business I mean. But there’s some bad air about it.”

“The tourists don’t know that. And that’s good enough, isn’t it?”

I turned to them, greeting them and raising my beer, and they replied to me, clinking their glasses. They were in a relaxed mood. I thought I’d give a little investigation a go here.

“I overheard you talk about the hotel, the Forest Hotel, I’m staying there. I’m just curious, may I ask what’s the bad thing about it?”

They dropped their smiles. They looked at each other and one of them said, “Nothing, it really is a nice hotel, isn’t it? Although the owner—” His word was cut off by the other man’s motion, who shook his head. Both of them fell silent and now were staring at me. Unnerved, I looked around. I noticed all the customers around us and the bartender were looking at me. After a second they all went back to their conversations. The two men resumed talking by themselves, more quietly and their bodies turned away from me. Sitting alone again, I took a sip from my beer.

I didn’t know what time it was when I left the bar after two more drinks, but it was probably quite late. As I stood in the empty street, it occurred to me that I should take another look at the hole, the second one. It shouldn’t be so far from where I was, and there might be less police, I thought. It was as if I was being pulled towards it. I just needed to see it with my own eyes.

After walking for about fifteen minutes, I saw the yellow caution tape gleaming under the street lamps. The buildings surrounding it were completely dark and there was nobody around. I approached the scene and went over the tape. Two metres from the tape, the grey of the asphalt turned into the brown of the soil, and then into the nothingness of a circular shape. I stood at the edge and looked down. It was as wide as the one in the forest, but on a city street among buildings, and in the darkness of the night, there was more strangeness to it. The nearest street lamp was flickering. Even when it was on for a moment, I couldn’t see the bottom of the hole. It was only darkness, black. Staring into it, I started to feel no word could describe it. What would I say to that immigrant man if he were to ask me again, this time to describe it in my own words? How could I write about this? I stared into the hole. Then, the nearest light went off, leaving me in the dark. There should have been other lamps on the street but all the light was gone around me. Startled, I stumbled back a few steps, my gaze still on where the hole had been. I started to panic. I imagined the hole expanding in the dark, reaching towards me to swallow my body. Then, after a few seconds, the light turned back on. The edge of the hole had stayed where it was. I had reached the caution tape. I stepped over it and stood behind the marked area, catching my breath. I needed to get back to the hotel. I took out my phone to call a taxi and started to walk towards the centre of the city. There was no way I was looking for the bus stop in the dark.

I was still feeling uneasy when I reached the hotel. The owner was still at the counter and greeted me as I entered. It only occurred to me then that it was strange she had called me to bring me the news of the second hole so early this morning. I approached the counter and she asked, “How can I help you?” I hesitated for a moment and then said, “You know something about the holes, don’t you?” Her polite smile disappeared from her face. We stared at each other for a few seconds. She then said, “Yes. I know you are here to know about them, too.” She sighed. “That is why I called you this morning. I apologise I disturbed you so early,” she said, “but I know people in this city, and they bring news to me. I thought I should inform you.”

“Um, thank you,” I replied. “But why do you care about it so much? You sounded like you knew there was going to be another one.”

Her blank face didn’t change, like she was wearing a mask. “I have grown up in this city. I have seen many things happen. When I was young, before I inherited this hotel from my father, those sinkholes appeared. About forty years ago. And,” she hesitated for a second. “There were some… unfortunate things.”

“What things?”

“Some people disappeared around the time the holes formed.”

“Disappeared?”

“Yes. Three people went missing. All of them were young. They didn’t find them. But memories fade over the years, at least on the surface. People forget. And they don’t let visitors see what they do remember. Or not the bad things, at least. And then there are those who are drawn to these occurrences. Anyhow, people still come here. That is why I still have this business.”

Silence fell between us. Then I asked, “Why are you telling me this?”

“I thought I would warn you. You might see bad things if you dig too deep.”

There was a hint of worry to her voice. But I was more alarmed than reassured to know she was worried about my safety.

I remembered the darkness that greeted me as I looked into the depth of the hole, and became aware of the dimness in the lobby. I looked at the hotel owner in the face.

“Thank you,” I said. I could think of nothing else to say. She smiled. I thought it was a strange smile. Sad and bitter, but there was also something else beneath her smile, like she knew something bad was going to happen. Looking into my eyes, she said, “Have a good night.” I left the lobby and went back to my room.

When the phone rang the next morning, I was not surprised. I had not been able to fall asleep. The image of the hollowed-out ground stayed in my mind. I felt as if it was going to swallow me if I closed my eyes.

I picked up the receiver. The owner’s voice said, “Another hole appeared. This time in the east part of the city. And,” she paused and I held my breath, “a child disappeared.”

I arrived at the scene in a taxi. I got off on the wide road a few blocks away from where a crowd was forming. It was on the eastern side of the city, where the old apartment residential blocks and the immigrants’ apartment complexes met. As I hurried towards the wall of people, I heard some excited voices in both languages. There were no police yet. I reached the crowd and made my way through, pushing people till I could see the scene.

The hole was in the middle of the road, as big as the first two. People stood surrounding it, leaving some metres of distance from the edge. But they didn’t seem to be paying attention to it. Instead, at the centre of the attention were two men, one in suit and the other the man I had translated for the day before. He glanced at me but turned his face back to the suited man immediately. The two men glared at each other and the blankness in the crowd was now replaced with anger and excitement. The man in the suit shouted, “You took my child, I know it! I know it!” So it wasn’t an immigrant child that went missing, I thought, but before I could form another thought, the immigrant man turned to me, and without thinking I translated what the man in suit had said. His face twisted with anger and he shouted back in his language, “What do you think, you always look down on us, don’t you see, just because I’m not from here!”

“My child is missing, I knew you people are here to do something to our children! We knew it!”

“You people are strange, the earth splits up and you don’t think anything of it!” Without understanding each other, they were shouting, and they now grabbed each other’s clothes, pushing and shoving, joined by people from the crowd. Wait, the hole, you are getting too close, I wanted to yell, but couldn’t say a word. When I thought they were going to fall into the hole, I heard the siren of the police cars.

The officers struggled to get to the centre of the crowd, now gathering at one side of the hole. Four officers took hold of the two men and pulled them aside to their car, while the others surrounded the hole with red signs and tape.

The police left and the crowd slowly dissolved. I was left standing alone next to the scene. I looked at the hole, gaping wide towards the sky. It was all wrong, the shouting, the missing child, people fighting beside this strange thing, the sinkhole itself. Nothing made sense. I was scared. I had avoided admitting it until then but now it was so clear and so clearly wrong that I couldn’t pretend not to be afraid. The hotel owner was right, I thought. People should have been careful. I should have been careful. I didn’t know how, but I should have.

When I went back to the hotel, the owner was not there. Or when I checked out the next morning. It was my third morning, the day I had planned to leave anyway, but it felt like running away. Something compelled me to leave, to go as fast as I could. I felt both drawn towards and pulled away from the holes. Something told me I had to leave. I needed to get away.

I got into the taxi, and as it headed for the airport, I looked down and stared at my hands on my knees. We were halfway there when the driver braked to a sudden stop. I looked up and said, “What’s happening?” But before I got the answer I saw it through the front window: a dark circle of nothingness emerging in the road. The driver tried to back the car up in panic but it did not move. I sat frozen in my seat and listened to the quiet sound of the asphalt tearing, bit by bit, until the taxi started to tremble. Then came a big sway and everything turned to black.

・・・

I walk to my workplace in the mornings. I prefer it to taking transport. And I have an irrational dislike for cars. I get cold and nauseous. Maybe it’s the lack of sleep. These days, I often wake up drenched in sweat from nightmares I can’t recall. It makes me forget things and makes my senses strange. There are gaps in my memory. I don’t know, for example, why or since when my boss has looked at me with worry in the eyes and my colleagues avoid me ever so slightly in a strangely polite manner. But everything feels strange anyway, too bright for my tired eyes. This morning, too, my sight is blurry and my thoughts are unclear from last night’s interrupted sleep. I feel like there are black circles all around, on the sidewalks and escalator steps, where things disappear from my sight. I rub my eyes with the back of my hand.

In the office, today’s newspaper is placed on my desk. My coffee slips out of my hand as I read the headline on the front cover. “Sinkhole appears in Eastern District.” Underneath, an aerial photo of the familiar park in my neighbourhood, only with a large dark circle on the green grass. I stare at the black hole in the photo. I hear the sound of eroding soil in my head. It begins to lull me. The image of the dark hole starts to swallow my thoughts.

Miyu Sasaki is a second-year student from Japan studying Literature and Rhetoric at BCB.

The Sinkhole was written for professor Clare Wigfall’s fiction writing workshop.