“The story so far:

In the beginning the Universe was created.

This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move.” (Adams, The Restaurant at The End of the Universe)

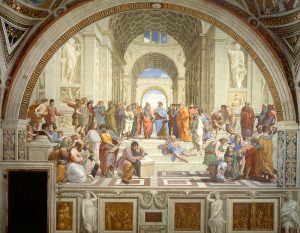

Whether the core was excavated from the bowels of the Earth 15 years ago or 500, the fact remains that Plato’s Republic is a timeless piece of philosophy that embodies the very essence of the discipline. It not only provokes a constant reinterpretation of our understandings and beliefs, but because the subject of the book is the human soul, a phenomenon unchanged from Socrates’ time despite changes in the environment, its relevance remains regardless of the epoch.

No matter how much thermodynamics likes to emphasise that time is the only constant, it cannot be denied that some times seem to change disproportionately to others. Athens isn’t the same mild-wintered, Mediterranean wonderland it was when Socrates frolicked in the streets: the tides are changing, and people must adapt to the urban heat island effect in the city centre if they want to survive. This is why, on noticing the general unrest in the student mind regarding Plato and the (long dead) old (white) man’s place in the twenty-first century, I felt perhaps it was time someone wrote a Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Republic, to show what one can expect when opening this treasure-chest. Here’s what my Guide has to say about the unbelievable things they talk about in the Republic:

Listen, Listen:

“In the next place, get yourself an adequate light somewhere; and look yourself — and call in your brother and Polemarchus and the others — whether we can somehow see where the justice might be and where the injustice…” (The Republic, 427d)

The Republic is a journey through space and time. It is a constant up and down, up and down from the Piraeus with Socrates and his band of brothers in the quest for not only justice, but also the truth and the good. But what is it that they’re doing? It is not like other philosophical texts, it’s not a treatise. There aren’t a set of pre-established aphorisms that Socrates puts on the table and expects you to digest. Instead, he draws the boys into a dialogue, draws us into a dialogue, and we traipse through cities and caves, feasts, the shire and Erebor (Lord of the Rings)*, all in the span of ten books. And Socrates lets the ideas speak first: Plato believed that ideas cannot stand independent of their introducers, so precisely for that reason does he dispatch Socrates, in the Republic, to take hold of that idea after (its) introduction, to pull it out from its conceptual gunk and toss it in the air for all to see. He pulls the boys to the homes of those ideas and lets them see what they are like, what they have to say for themselves, before speaking himself or letting others speak about them. Socrates says:

“As for knowledge and truth, just as in the other region it is right to hold light and sight sunlike, but to believe them to be the sun is not right; so, too, here, to hold these two to be like the good is right, but to believe that either of them is the good is not right. The condition which characterises the good must receive still greater honour.” (The Republic, 509a)

Here, Socrates says knowledge and truth are not the same as our belief of them. What we see, and hence associate, is just the superficial layer (physical reflection) of an intellectual concept, and it isn’t right for us to mistake this superficial layer to be the concept itself. Maieutics (the Socratic method of cooperative dialogue) recognises this, and, through dialogue, introduces other perspectives to further the quest for a deeper understanding of the concept at hand.

Not only does Socrates lay down the structural basis for the investigation to arise from and teach us the valuable skill of listening before speaking, but he also encourages us to recognise that we aren’t the beginning and end of our ideas: our beliefs stem from a more raw concept which, through personal understanding, gets wrongly associated as the limitation of its origins.

And aren’t these skills critical to learn in this day and age, where talk is elevated to the same status as dialogue and discussion, where questions are hesitant to be voiced, and where most people are more eager to talk than to listen and think?

Socratic Irony:

There’s something special about Socratic irony. Not only does it make his interlocutors feel special about themselves, but it also plays an important part in helping them realise what’s lacking in their argument. Let’s take this a step further. Imagine the Republic were a postmodern psychological thriller set in a grungy urban hotspot. For technical ease, we’ll take Glaucon as our protagonist.

Glaucon is a morally ambiguous character who leads a double life. By day he’s the good boy — he goes to university, eats his lunch in the cafeteria, and turns up at the post-office for his part-time job. But by night: Oh, it is at night that Glaucon transforms into a completely different individual. As his inner demons are unleashed, he becomes at war with himself, trying to rein in his fancies and desires in order to remain respectful of his accommodation in society. But he cannot do it alone; Glaucon’s soul vibrates with the echoes of war. And that’s where Socrates comes in. The stress of moral responsibility and the intensity of his desires lead to Glaucon’s development of a defense mechanism, which he calls Socrates. Socrates comes out to play whenever Glaucon has either questions he knows the answers to (but which he is yet unaware of), or when Glaucon’s beliefs are inherently flawed. And what does Socrates do? He pretends to be dumber than he is. Socrates, despite knowing the answers to his questions and the flaws in his argument, guides Glaucon by interrogating him under the false pretense of not knowing any better, until Glaucon realises for himself that his argument or belief is (indeed) flawed.

You might be thinking, ‘wait, so why did we have to go to a postmodern urban hotspot if you just wanted to show that Socrates helps the band of brothers until they reach their ‘aha!’ moment?’

The answer to that lies in this very same scenario. What Socrates is, in this postmodern setting, is a part of Glaucon. Sure, in the Republic, Socrates goes beyond just this by helping Glaucon from a distance, being the optician when Glaucon’s vision is limited. But since postmodern Glaucon doesn’t have a postmodern, live Socrates at his disposal, he would have to make do with his own Socrates (and maybe, just maybe, reading the Republic). What Socrates does in the Republic is take the arguments and beliefs he thinks his interlocutors know the answers to (or those he suspects they are arguing for the sake of arguing, despite knowing better) and guides them, through his intentionally naïve questions, to realise the flaws in their arguments and beliefs.

And isn’t this a valuable? Rather than rely on an external Socrates’ to help us find our way back to the path of inquiry, isn’t it more fruitful for us to develop the skill of effectively questioning our own beliefs? You don’t need to be the ancient Glaucon when you can train your mind by reading the Republic. Why not learn to make space within yourself, like postmodern Glaucon did, to be (y)our own Socrates?

These sort of questions — whether an idea is rational, practical, or has more benefit than drawbacks when applied in real life — are things that we must learn to employ, as Socrates attempts to teach his interlocutors. Not only does it teach us the important skill for self-reflection and critique, but it provokes us, even today, to bring our existing structures, internal or external, into question.

Constant Return to Verticality:

“Know Thyself.

Kind regards

The Oracles of Delphi”

If you have ever wondered, lying in bed, just how long it would last if the Republic were to be a real conversation, you are not alone. But, if it were to be a conversation, they’d have to start at some point. And in the Republic, they start their exchange while going down to the Piraeus. This constant play of up and down, up and down, not only in the real city where they have their dialogues, but also in their city-in-speech, their paradigms, ascent and descent from (and into) the cave, aren’t just allusions to the nature of movement in physical space; they are telling us something important. To determine what this could be, let’s look at the verticality in the allegory of the cave:

Shaken loose of his bonds, man ascends from the underground to the alien realm above, of which he had no knowledge of outside the shadows of the imitations which he grew up with. But to get out there, he must pass through that elevation where the artefacts corresponding to the shadows rest. Finally, despite being up there, dazzled by the light of the sun and the alien landscape around him, his first action is not to immediately look up, but it is his compulsion to look down at the reflection of the sun in the water. Only once accustomed to that can he dare try looking at the sun itself. And, once he looks at the sun, he cannot help but be dragged into the realm beyond, into the metaphysical, where what he saw on Earth can be explained as that which was merely the reflection of the intelligible realm, on the other side of the divided line. And once he undertakes the responsibility of understanding the intelligible, again he is compelled to go down into the cave to not only reflect on what he learned, but also to try and inform — to persuade the ones still inside the cave to disregard the shadows as the real thing.

One could read this constant emphasis on verticality and the return to it as a guideline regarding the importance of recognising not only the vertical distance between us as Beings present-at-hand and the ontological phenomenon (the good, the truth) being explored, but also as a suggestion to establish a frame of reference within oneself to always come down to in order to reflect on the knowledge obtained while up and away.

It is a journey when you venture out with the flow of vertical movement in a quest for understanding an ontological phenomenon and its metaphysical functionality. But even if that’s not the specific goal you have in mind, there is an undeniable desire within all of us to constantly keep getting better at things, to reach for new heights. And if this urge is not a recognition of existent verticality, then what is? And, in that case, what Plato’s Republic tries to teach us through the (mainly upward) movements of Socrates and the boys is foresight. Be prepared while undertaking a journey to the stars, have fun along the way, but be sure, from time to time, to look down at the Earth and contemplate what the experience teaches you about the Earth itself. And who knows, maybe it will change you. Maybe, in your quest and contemplation, you will find a way to interest the Earth to be better.

What the verticality also teaches us is the important role of liberal arts education in changing the world. When we study humanities, (yes, that includes economics, and politics) we study the human being, and our natures and behaviours recorded over the length of time. The soft skills we learn and exercise through discussion of core texts like Plato’s Republic elevate us above the structures we inhabit to look at the problems objectively. And, in the end, why the philosopher king (why we) must come down is not only to put that education to use amidst his (our) fellow cave-dwellers, but also to enhance that education.

The constant vertical back and forth is the re-telling of our very human story.

The Republic as a Commentary on Politics and Practicality:

Who says the Republic is not practical? It isn’t for nothing that philosophers, political analysts, economists have been returning to it for centuries. If, despite all the ranting above, you’re still wondering ‘okay, but why do I have to read the Republic?’ then let me spell it out for you.

Let’s take the Republic as a political commentary: Plato perhaps used the Republic as an experiment with political structures. One could talk forever about the ironic metaphors and concepts in the Republic— the prevention of social mobility, feminism, militarism, totalitarian modulation, eugenic principles, abolition of private property, etc., which all act as provocations for thought, and still not be done with it at the end of the day. But for now, let us stick with Book Two, and listen to the echoes of 2017 time-travel all the way to 380 BC.

While undergoing structural changes, Glaucon’s luxurious city hits a roadblock due to the unstable nature of the guardians; this prompts a discussion regarding their education. The question that makes training and education the main focus of the next segment is how to deactivate the unpleasant aspects in the nature of the guardians to make city life as pleasant as possible. While deliberating on the order of education and the forms of speeches, Socrates and Adeimantus arrive at those pesky “makers of tales” in the city with their overactive imaginations and excitable characters. The question is their influence in the city. Socrates and Adeimantus determine that all that these “makers of tales” produce must be approved by the State before permitting the same to be distributed. Soft censorship, which can also be seen as prohibition, is discussed extensively in Book Two — for example, with regards to the withdrawing of access to certain texts (like Homer and Hesiod) to prevent the corruption of the young learner’s ideas about notions like the gods and socially acceptable behaviour.

This isn’t far from today’s reality, where it’s not just news that is heavily censored to make it ‘more digestible,’ but also many kinds of art and speech, until we’re left uncertain whether that freedom of expression which most of our constitutions advertise is actually so free. And the point that Socrates is perhaps trying to make, especially as the formulations get more ludicrous as we go through the successive books is just that: to make his interlocutors realise the flaws and horrors of their beliefs and contemplations, which, in turn, prompts us to consider examining our own.

But doesn’t it tell us something, to see a book, written two-thousand-four-hundred years ago, speak of the things we (still) grapple with in 2017?

Just like the supercomputer Deep Thought in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy uses the “Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything,” (42, if you did not know) as a reference to find the question to this answer, the Republic reads as a book of answers that leads you to formulate your own, deeply thought, complex set of questions. But it doesn’t have to stop there. Unless you open yourself up to the possibilities it offers, it won’t be as practical as you were hoping it would be. After all, things are often what you make of them.

The invitation is there. It is up to you to determine your level of participation.

And, along the way, instead of just taking away the skills, the questions, the quite amusingly pitiful attempts at humour, isn’t it more rewarding to engage in a conversation with the text, make it a companion, a guardian, so it stays with you for as (annoyingly) long as you let it?

“Oh dear,” says God, “I hadn’t thought of that,” and promptly vanishes in a puff of logic.” (Adams, The Ultimate Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy)

___

Notes:

*The Ring of Gyges: In Book II of the Republic, Glaucon uses the myth of Gyges, which tells of a shepherd who finds a ring that makes the bearer invisible at will and who uses it to seduce the queen, kill the king, and take control of the realm, to support his point that a just man is just only because of compulsion. He argues that both a just man and unjust man would choose to act unjustly if they didn’t stand the risk of exposure and the externally imposed consequences.