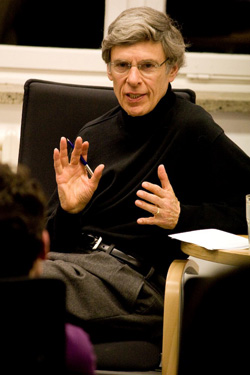

On the 22nd of February ECLA hosted a lecture by Professor Richard Kraut on his book What is Good and Why: The Ethics of Well-Being (Harvard UP 2007).

Richard Kraut is a Professor at Northwestern University. His interests include contemporary moral and political philosophy, as well as the ethics and political thought of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. His other works include Socrates and the State (Princeton, 1984) and Against Absolute Goodness (Oxford, 2011).

Kraut’s lecture was not like any other given at ECLA, since it opened with comments and questions of Visiting Professor Brendan Boyle and Dean Thomas Nørgaard. They both tried to elucidate what they found particularly interesting and challenging about What is Good and Why.

Brendan Boyle called the book “an achievement” in the sense that it manages to give lucidity to questions that we rarely pose out loud. Due to the apparently mundane nature of these questions, we fail to inquire into their significance for our own reasoning, relationships and life.

Brendan also presented the book as an excellent example of “moral naturalism”. The question of “what is good” inevitably leads to the notion that something is good for something or someone. The good is relational. Thus, our understanding of it need not pertain only to human beings, or as Brendan put it: “What is good for human beings is on a par with what is good for bees, wolves, etc. We are asking about one and the same relation”.

Thomas “sketched” the three crucial questions addressed in the book: what does it mean for something to be good for someone or something; which things are good and what role should categories of good and bad play in our practical reasoning? For Thomas, the first question is the fundamental question of the book. When we use the categories good/bad we already bear in mind the notion of the relational nature of the “good for”.

We should investigate this relationship and focus on how any notion of “good” leads back to the idea that the good is so because it is “good for”. With regard to the second main question, we should look at the process and growth of a thing to determine what is good.

The good is the potential for the growth and flourishing of a being, whereas what is bad is any impediment to this potential. With respect to the third question, Thomas’ reading of Kraut goes back to the fundamental importance of the first question: that in our practical reasoning we should focus on the relational character of the ‘good for’ and thus derive the categories of right and wrong from this investigation.

Kraut described his theory as partly a continuation and revision of Plato’s thought, partly humanistic, and partly naturalistic. It is also a value-oriented theory, opposed to deontologism to the effect that it does not take the categories of “right” and “wrong” to be absolute––in their prescription of action–– regardless the circumstances, but rather pertaining to the “good for” a being: the rightness or wrongness of telling the truth is determined by whether such action will promote or undermine the development of the being in question.

Kraut believes that the first philosopher to make the good the most important form to be understood was Plato and he begins from Plato’s investigations. He wants to defend Plato to the extent that if we do not grasp what the good is, we will be in great difficulties. But since Plato concerns himself with what the good is in itself, and not with what it is for someone or something, Kraut takes up the task of elaborating the good in its relational character.

He also considers himself a humanist, insofar as he believes that the good should be looked for in what is good for the human being and not in some remote abstract form. He distinguishes himself from the humanistic tradition in that he wants to seek out the ethics of well-being beyond the notion of the purely human: the importance of animal well-being is independent from human. He adds, “Human well-being takes priority over the animal, but not absolute priority”.

Kraut distinguishes his theory from the Platonic not only in focusing on the relational character of the “good for”, but also by insisting that ordinary people know a lot about what is good without being in the know of Platonic transcendence: right and wrong figure more in practical reasoning than in philosophical dialectics.

He also distances himself from the consequentialist concept of the maximization of the good and the independent notions of wrongness and rightness. He endorses a prescriptive independent notion of right and wrong only in the case of social norms, insofar as they are a means of protecting some important values and thus a being’s development; for instance the social norm characterizing adultery as wrong takes the emotional well-being of a subject as a moral value.

Kraut’s “moral naturalism” borrows and develops an idea present in Aristotle: human beings are political and rational animals. What is found in their animality is present in plants and other animals as well, viz. the potential to grow and flourish; so what is good for the animal and plant is also good for the human, with the difference that the human being has a particular good and that is his or her reason.

What is good for the human being, as for the animal or the plant, is defined with reference to the capacity of each to develop to the full potential of their kind. Thus, ultimately an ethical inquiry will also involve an inquiry into the nature of being, or the nature of a particular “creature” and what is good for its growth and flourishing.

Maria Androushko (1st year BA, Bulgaria)