I go out walkin’ after midnight

Out in the moonlight

Just like we used to do, I’m always walkin’

After midnight, searchin’ for you

-Patsy Cline

I don’t know if you remember that first night you closed my chest and opened yours, but it was wet and dark. All day the sky had been grey over the city. The clouds had hung low and sharp, and, although the rain had stopped falling by the time I found you, there were still puddles mirrored down in the street. They’d crowded between the cobbles and winced every time the wind dragged down a shimmer of drops from the trees, then went still again, went quiet. Mostly the only sounds were our feet as we walked along the sidewalk: my slow steps, and your quick. There weren’t many cars, and it was early spring, so the leaves weren’t quite out yet and flapping.

In a couple weeks maybe, I told you, and we’ll be able to see them. In a couple of weeks, that’s all. And you know how you are: stubborn; you said that was too long. I said well, we’ve been waiting all winter and again you said that was too long. You were tired of the snow, tired of the cold. You wanted warmth, although there was a shiver in the way you said it. I glanced down at you, but your eyes were somewhere far ahead. Your feet padded next to mine, the wind stirred your hair, but it was as if, however close we were, there was an ocean at work—one that could transmute and distort distance, hiding among our voices to later reveal itself deep and fathomless with silence.

It was one of the things I had come to grow used to in our time apart, and from what you told me, something you had never come to fully accept. We almost didn’t want to say it anymore: “It’ll be over soon.” It sounded so trite, like telling a child a lie to make them quiet. Afterwards, you told me you never even believed it. Then why did you say it? I wanted to say, and yet I never found the courage. Perhaps I was scared of the answer. The ocean that had buried itself between us had begun to drag you down by your chest. What I soon came to find out lay within it had grown too heavy, and that night was the first time I saw what was really happening to you, and realized, with a terrible guilt, that it was all my fault.

I’d never meant to hurt you. Sometimes it felt like you understood that, but other times you would just ask the same thing again and again, and I wouldn’t have an answer:

“Why did you leave me?”

“I didn’t leave you.”

“But you’re not here.”

“But I’ll be back.”

They tended to tumble over each other like that. To stumble and lurch until I always broke: “I don’t know why I’m not there with you. I don’t know why I left.”

I have a soft voice, but they were never spoken softly. There was always a texture to those words, something coarse that scraped the inside of my mouth and planted ulcers along my gums. They were the truth, and yet they weren’t supposed to be. I had taken a job, a short technical training at a theatre company with a good name. I hadn’t just left. I was working, and that was supposed to be the reason. And it was the reason I told you before I left, the reason I told myself on the plane, and only when I landed and found my apartment, walked in and saw a skeletal white room with nobody in it but me, did the reason shrivel away and hide itself in some crack in the wall I could not find. I set my suitcase down, did not cry, but tried instead to convince myself again. After this I could get a real job. I would know people in the right places, people that would talk to other people and help me work the sorts of shows I wanted, or at least move me one step closer. It was hard to understand that, then, in that place.

I wasn’t even able to sleep. Once night came, the bed felt too vast, too cold. It was a small bed, but it was only me in it, and there were too many sounds in that part of the city to feel enclosed: construction; busses; tourists. Always something making sound. And so I would hammer my eyes shut again and again until sleep answered, waiting. I did not dream. I did not get to escape. Instead, I found that for the first time in a long time, I was wholly inside my body. With you, I had had the ability, if I needed, to disappear, or to pretend that I was someone else, even if it was only for a day. I was able to store pieces of myself in your life, or your worries, and forget about my own. There were so many of them that you did not know back then, and one by one they sat on my chest, night after night. Slowly, I think the fatigue numbed me; and at around five days my body collapsed in on itself, and turned out its lights.

When I woke that next morning there was the pain in my chest.

I don’t know if I ever told you about the pains I would have as a child. I might have, but I think they scared me too much to ever talk about them out loud. My doctor, Mr. Helmrich, had told me that they were nothing more than the lining of my lungs sticking together, and pinching—“nothing to worry about,” he assured me. It was called the pleura. And, to illustrate, he slipped from out of his yellow folder a diagram on thick paper with an internal palimpsest of organs and muscles crossing and recrossing, pointing here and there with the butt of his pen. I went home believing none of it. I did not trust doctors back then and still only pretend to—which meant the next time it happened some days later, just as the times before, I thought my heart had stopped and I was going to die. My body would go cold, first, after the initial pinch, and I would stiffen. I would have to cave in my chest and hold my breath, but I never completely could, and I would feel the stabbing, the twisting of the knife between my ribs, the terrible aching emptiness of after. And that’s when I would begin to shiver—and would not stop. Once, when I was nine, I tried to take a warm bath, thinking maybe that the heat would calm me, and when that didn’t work, I tried to lie down in my bed with all my covers heaped on top of me. But I was made of worms, it felt like; grubby, squirming things that wanted to burst out of my skin, only my pores were not big enough for them to fit. I never told anyone that I was in pain. I would try to act as invisible as possible so that if someone saw me, saw whatever nervous fear was coloring my eyes, they would not feel inclined to look again, merely forget I had even been there at all and return to what they were doing before.

I suffered alone that way. It was how I wanted it.

The curious thing, though, was that I never felt them when I was with you. They seemed to vanish altogether somehow, and maybe that’s why I never brought them up: they simply weren’t around. For the three years we had lived together, not once had I felt the pain in my chest, and so that morning when they came back, I had believed it was the same sensation. Only the more I felt it I realized that it was, in a strange way, something else entirely. The one I felt as a child was a stabbing. It was a pointing, puncturing sort of pressure that dug and burrowed, and then bloomed outward. This new one was a scraping. And it was heavy. It wasn’t just that I couldn’t breathe now, but that I couldn’t even bend myself down to tie my own shoes. It was always there. And no matter how tired I was, again I couldn’t fall asleep. It didn’t matter that I was exhausted; in fact it hurt more to lie down, as if there were not shards of glass but one great bulk of it grating and grinding inside me. At some point I stopped trying, didn’t even bother with the bed, and from there, well…

I had always liked to walk at night.

You remember. The burring cicadas, the snoring grass—the way the wind sighed and brought the blue coolness of the river up the hillside like a subtle perfume. I took you with me once and you suggested we do it every night. “Our moonlit walk,” you called it, even if the first couple nights were covered with clouds. They were our time to talk about whatever we wanted, or to laugh at things only we thought funny, to feel the air as much as someone else’s skin. I guess I missed that. I missed that place where the land opened up like a book and kept on opening. Pages and pages of hills, of valleys, of sunset. But most of all I missed you, and in some corner of my mind, maybe, I thought I’d find you. It wasn’t really a hope, or a dream, but something I wanted, that’s all, something I needed.

I started with just a big loop around the block. I’d pass the tram stop, and the old church, the French bookstore, the park, end back up at my apartment. It felt good to be out in the cold, again, and the quiet. The times it rained I didn’t even bring an umbrella. I let the drops tap over me and soak into my clothes. Later I’d stretch my loop, extending to the airport where I’d press up against the wire fence and watch the planes land and rise and land again, until the sun broke the horizon and I’d start back the way I’d come.

I developed a rhythm. When a siren would sound I’d listen. When a car sidled past I’d watch. And when a person appeared I would not look at them, but cast my eyes to my feet, and for that I am sorry, too. I do not know how many times I must have walked past you, before finally looking up and seeing you there, under the moonlight, waiting for me.

You had been walking too, you said. You hadn’t been able to sleep. Your body was tired but your mind whirred, and, feeling trapped, you had started to probe out into the night, going to the gas station, the church, the cemetery, the farm. You were living in that small town just up off the Hudson, in the first house we ever shared, and it didn’t take long to reach its edge. There was the farm you came to, you said, laid over a low rolling hill, the other side of which was a great open field of dead grass, and, beyond that, a heavy fog shimmered finely with lucent points of light. It was the furthest part of the town, and yet there seemed to be something on the other side — something other than mere farmland and road in the fog and the lights, and so you kept walking. Just as I had kept walking. Until somehow we had found each other in a strange city that was neither where I was nor where you were, but as if the two had been sewed together without any logic or idea of continuity. A dark field stretched out of the first floor of a building; a car was driving, blindly, in a forest; there were deer, four or five or even six of them crossing the cobblestone street.

And yet when I tried to take you in my arms, and kiss you, feel the shape of you, I didn’t feel anything. I could see my hand on your cheek, see it glide up into your hair. I could even see my fingers stretching apart your hair, and moving it, but I could not feel it. What touch we had was gone, and although we could talk, and see and hear, and it was good, and it was better, it wasn’t what we had before. Over time, I think we grew as accustomed to it as we ever could. It was never easy. Each night we’d meet and talk about our day first, or talk about what we’d do when I got back, but pretty quickly we’d quiet down, grow angry; not at each other, but at the sheer intangibility of it all, the distance we knew was there but could not fathom. An ocean, after all, is only ever as big as the horizon allows. What’s beyond almost doesn’t even exist.

“But do you think I could bring you back?” you asked, out of the blue, one time.

I didn’t know what that meant.

“If I take you back the way I came,” you said. “If I bring you with me. Do you think it would work?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

We’d met and started to walk as we usually did, that night, through the wet and the dark. The trees branched over us and the streets gleamed like metal. By then it was long past midnight—about the time that we’d have to split apart and head back. We found that if we stayed too long in that place it would start to rot and decay. Things wouldn’t stay as they were. Roads wouldn’t lead to the same place. It would be the same road, but it wouldn’t carry us to the same destination. It would fork imperceptibly. One moment you’d be right there beside me and the next I would be alone, looking up at my apartment and its white cold face, so I didn’t know if you could bring me back with you like how you said. Of course I wanted to, but I just didn’t know.

And softly, too, I still felt the pain. Smally aching inside my chest. I rubbed at it with my palm every now and again as discreetly as I could. It wasn’t terrible. I could manage. But I thought it would have gone away when I was with you, and it scared me that it hadn’t. As we walked, you’d ask me if I was okay from time to time, and I’d have to bury my hands back into my pockets, make up some excuse so you didn’t worry. You had enough to worry about back then that I didn’t think it was fair to put something else on you like that, so I’d just say “I’m fine,” and keep walking. It was my own problem and I would fix it. I didn’t need to talk about it, or let you know—if I let you know, then it would become bigger than merely something inside me, become more real and uncontained.

And it worked, until then.

You took my hand and you started to lead me back with you. We turned left down a narrow road and then through an old schoolyard. It was dark and the streetlights were not quite as strong. There were tall hedges to either side of us, growing wilder and stranger like matted hair.

With each step the pain grew. I didn’t say anything.

I tried to keep up, but my breath had started to rasp and wheeze out of me. I tried to cave in my chest and hold my breath as I did before, when I was little, but it didn’t change anything, only made it harder to walk. Stumbling, the sidewalk softened into dirt and grass beneath me. The street ended.

We were walking towards a small pond. Further ahead there was the fog, hovering over the water. A soft, sliding shape mapped with a thousand glittering lights, all flashing and bursting and dying. I saw you tugging at my arm, but I had stopped walking. My mouth hung open, and a faint breath misted from my lips. You asked me if I was okay, like always, but I couldn’t answer. I only tried to keep walking, keeping my back arched and hunched, and not breathing, fearing to breathe. The closer we came to that place, that field and that pond, the pain in my chest grew. I lifted a hand and rubbed my chest to feel where it was, to maybe ease it a little, or quiet it, but I gasped and shuddered at the touch. There was a whiteness that flooded my eyes, and, when it vanished, I saw you had set me down on the grass by the pond and asked me if I was okay once more. I looked at you.

“No,” I said. There were tears crowding my eyes.

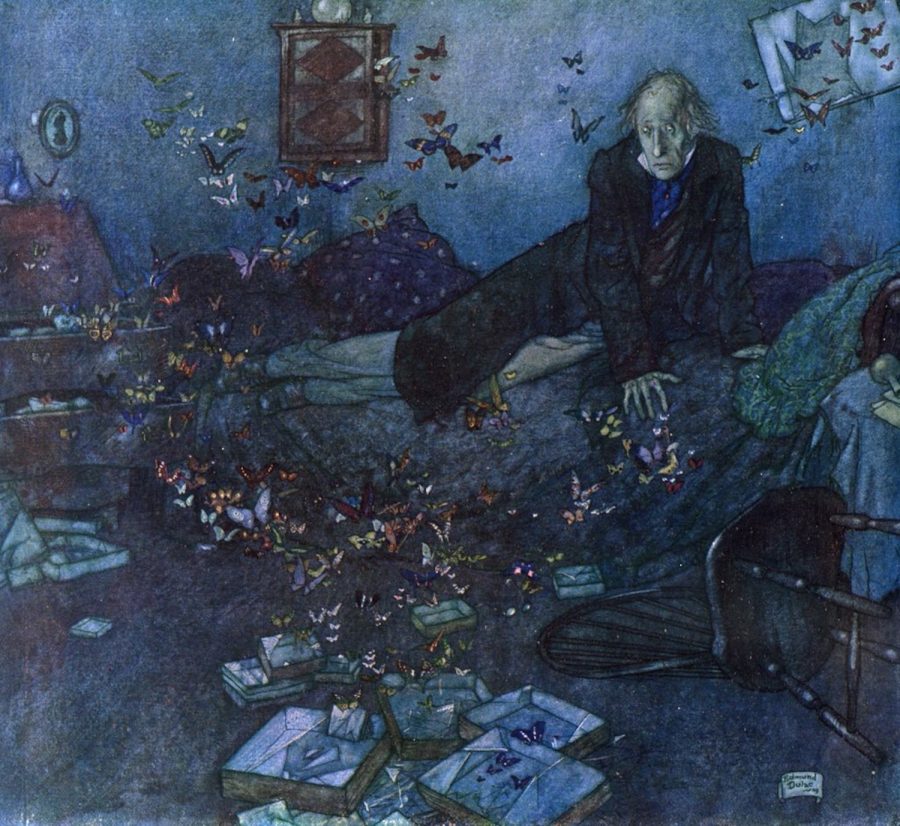

“It’s okay,” you whispered and pulled my shirt off over my head, laid it down. In an instant your eyes hardened and your hands searched my skin, feeling without touching. “It’s okay. Don’t worry. You’re okay. You’re okay.” Your fingers were like insects. When they found what they were looking for, they dug in, and there was a popping sound, like a bonfire spitting out embers. A little raised line showed down from my collarbone to my stomach. As if it were a door, then, it moaned first, a low, shadowy sound, and my chest was swung open, and it wasn’t messy, wasn’t bloody, everything was intact and whole. You held it there in your hands, my pale skin and my dark flesh, heavy on its hinges, and inside there was the white cage of my ribs and my pink lungs, my organs below, my arteries wound like wires. Looking at them like that my bones seemed so small and weak, like strange twine. Everything was in miniature, as if it belonged to a doll, and where my heart should have been, I saw, there was a silver locket instead, and your silvered picture inside it.

“I know it hurts,” you said, and you reached inside me, adjusted the locket so it would not scrape. You moved it off the bone.

“It will come back,” you said. “The pain. It won’t go away.”

The fog was growing darker behind us, and the wind had started to howl and barrel. Huge, chasing shadows darted and rushed, and yet the surface of the water was unmoving, like glass. You finished winding the string of the locket about itself and then, with ease, you closed my chest and opened yours, and I saw inside you: your heart. It was dark and slowly beating, and beside it, I saw my heart. Like a pair of dried figs they sat there, and only then did I see how you had to lean forward slightly with the extra weight.

“I don’t want to be here anymore,” I said, when I saw it.

“And I don’t want to wait anymore,” you said.

But the fog sifted down and grabbed you, started to pull you away. It wrapped around you like a shell and I remember trying to follow, trying to grab you and keep you, but the closer I came, I started to feel the pain again, the locket in my chest, scraping, stealing my breath. I kept moving, clenching my jaw tight and trying to open my chest as you had opened it before, to reach in and hold the locket in my hands, hold it out like a talisman to ward off whatever was in that darkness, and fight it and fight it… and fight it…

It happened like that every night. Just like that.

Only the first time I never said thank you. Not like the other times, when I knew. Not like then.

And so I’ll say it now.