I received an email from The New York Review of Books, though I do not remember signing up for their mailing list, advertising gifts for the Class of 2020. Enclosed in the email was a catalogue of thin silver bracelets with quotes from famous authors. The advertisement’s featured bracelet had a quote from Thoreau in a handwriting-like font that said: “Go confidently in the / direction of your dreams— / Live the life you’ve imagined.” I will not be buying one of these silver bracelets, nor have I learned, these past few months, how to bake sourdough.

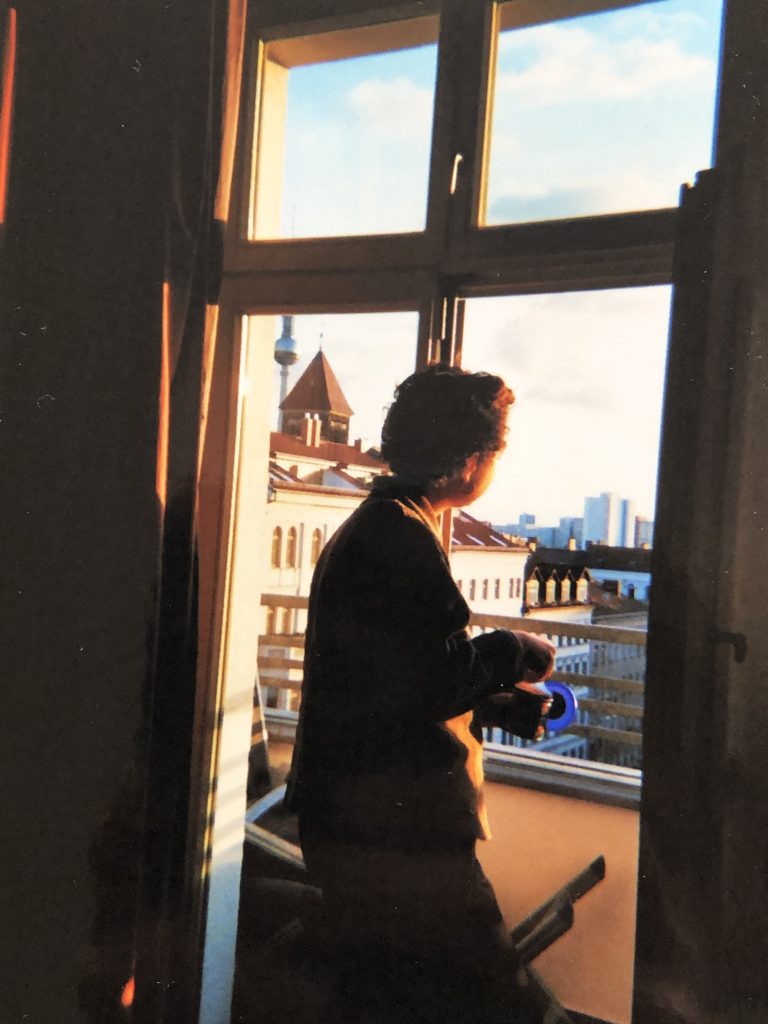

I remember a quiet day during self-isolation, day 5. I drink a soda on the balcony with my roommate, who is picking a spot of blue paint off of her stomach. The world is expressed to me as fragile, a condition which might have seemed obvious to others, but is new to me, at least on such scale.

On the street outside my apartment, a friend standing 1.5 meters away from me says, “It’s kind of like summers as a child, like when you would ring someone’s bell and they wouldn’t necessarily be home, and you would just go on a walk in the sun or something.” It is kind of like that but obviously heavier, our scene on a sunny street corner to the backdrop of pandemic.

This is hard to write. In part, because I am not a big fan of goodbyes but also due to the circumstances (I like that people, in general, prefer to euphemistically talk about ‘the circumstances’ rather than anything more specific). I wonder if this difficulty emerges from that particular breed of quarantine apathy. I read a COVID-19 dispatch from Rome, “Stop Making Points” by Francesco Pacifico, and Pacifico makes a good point about not making points: “When the outbreak happens, three weeks ago, our society’s reckoning comes in spurts. In very slow spurts. I remember feeling panic on a train from Paris to Milan to Rome, and I remember the panic receding, but after that it hasn’t ever been so linear, going up and down on a whim.” Pacifico continues, “I left a WhatsApp chat of fellow writers and intellectuals the other day because they were posting and scrolling through photos of the apocalypse like children. I couldn’t stand it. No takes. No points. Stop making points.” [*1] And I get this. Despite having graduated from BCB, an institution that most certainly cultivates its students’ abilities to make a point, I am finding that, “in these uncertain times,” I have none in particular.

“Have you ever thought about how if we hang out, it’s kind of like a petri-dish?” asks another friend via Facebook. My favorite cafe reopens, I see the same man I usually see, with a shock of white hair, who is wearing a large black blazer and reading the newspaper. He is sitting at the same table outside, sitting in his usual spot, almost as if two months hadn’t just passed by.

While on a circular walk around Prenzlauer Berg, I begin to wonder if what the Class of 2020 is experiencing is something like an inverse commencement. The traditional commencement honors the ‘graduate’ as an individual, and graduates are praised for newfound abilities that they have individually cultivated: technical, social, intellectual skills that they now bring into the world. (An article I read in a large and reputable publication said that the Class of 2020 would be remembered for “not giving up” and then proceeded to list a series of completely contradictory traits we needed to foster, e.g. that we simultaneously make decisions based on facts, and also be poets, and also be free-thinking. This seemed somewhat demanding.) A traditional commencement proclaims something along the lines of you have been trained to take on the problems of the world, this world is up to you, and yet this past semester has said the opposite of that. What we have encountered, instead, is not an emphasis on our individual strengths or merits, but rather an emphasis on our fundamental interconnectedness and even reliance on one another. This interconnectedness is even a biological imperative—that our collective well-being depends not on the individual but on the herd, simultaneously the stuff of metaphor and embodied, physical reality.

Despite this, that I mourned our cancelled commencement ceremony forced me into a sudden confrontation with a certain kind of selfishness. Was there a function, if any, to this kind of selfishness, at this moment? “I wear [my mask,] this conspicuous physical and sensory reminder of death and isolation, because I want the people around me to feel safer,” writes Amber A’Lee Frost in Damage Mag. “I refuse however, to wear that other mask, the facade of good cheer prescribed to me by the pathetic little tyrants this pandemic will hopefully put into perspective.” The great contradiction of interconnectedness is that it also requires a sum of individuals. Hence the agony. You are part of something bigger, requiring the recognition of us as individuals, choosing to be something else. The sensation is less like disappearing into some poetic sea of interconnected human beings and more like desperately changing your profile picture to be remembered as a physical flesh-and-blood being.

This is, of course, why I am grateful for Die Bärliner. I am grateful for the places in which interconnectedness thrives, particularly in a moment that illuminates global and national inequalities and injustices. “Especially when fighting from the margins, it is imperative to be seen,” wrote Elena Gagovska in her goodbye to the blog last year, which addressed this notion of interconnectedness and solidarity in writing. “And especially when having a platform — no matter its size — it is imperative for writers to bring those issues out from the margins and offer public support. That is what writing means to me.”

I am grateful for everyone who has written for this small platform and who has generously allowed me to edit their writing; I am grateful for the brilliant team of writers at the blog; I am grateful for my kind friends who let me run any idea past them (and with whom I designed a particularly thorough disaster plan involving meeting points at train stations should “the situation” escalate). Writing is a small task, but when done in the spirit of interconnectedness, I hope it brings us closer to the project of communal thinking that anthropologist Clifford Geertz describes: “At base, thinking is a public activity — its natural habitat is the house yard, the marketplace, and the town square.” [*2]

Notes:

[*1] Jessie Kindig, Mark Krotov, Marco Roth. “There Is No Outside: Covid-19 Dispatches.” Apple Books.

[*2] Palmer, Alan. “‘Introduction.’” Fictional Minds, University of Nebraska Press, 2008, pp. 11.