On May 8, Bard College Berlin had the opportunity to welcome Noam Libeskind, a researcher from the “Leibniz-Institut für Astrophysik Potsdam,” for a guest lecture titled “From Chaos to Cosmos: the history of the Universe as we know it.” Invited by Professor Michael Weinman for the Early Modern Science core course, Noam introduced some basic concepts regarding the physical properties of our universe, loosely basing his methodology on historical progress in scientific discoveries. In a series of PowerPoint slides, he showed how classical astronomy developed via Newton, Hershel, and Kant, and reached its peak in the modern research of Hubble, Eddington and Einstein.

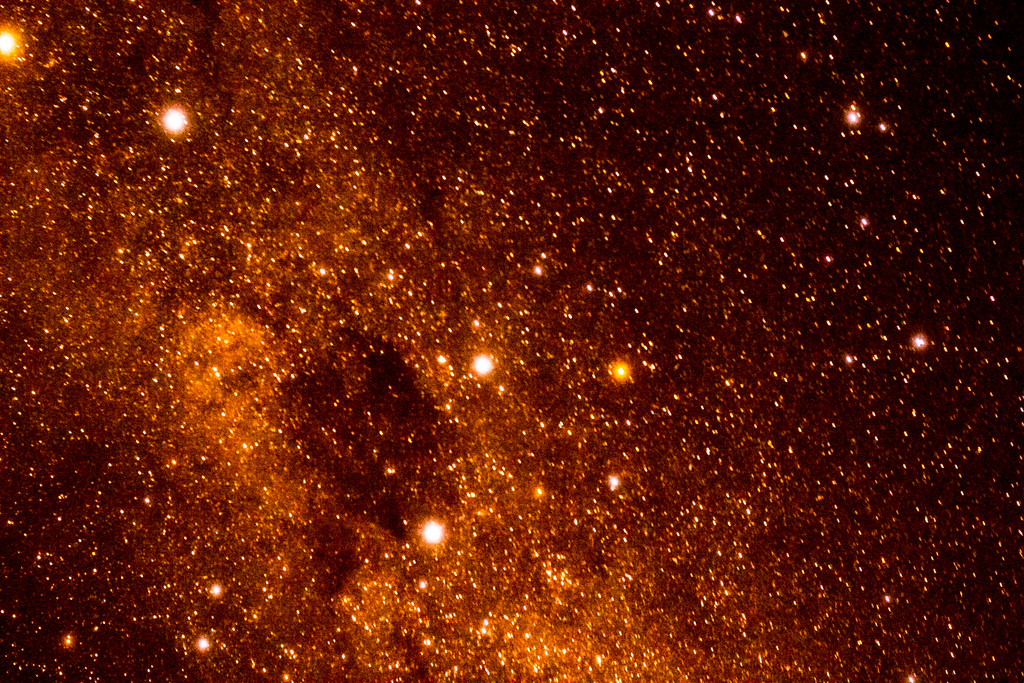

Although I found almost every slide that Noam Libeskind presented to us quite fascinating and worthy of its own story, I would like to share my reflections on the first photograph he exposed us to––the sky at night. The scientific progress in astronomy started with sky observations, and looking at a relatively clear sky without light pollution inclined me to think about the first sky observers––all in my attempt to understand their fascination with the cosmos better.

Even as a city resident, I frequently look at the sky at night. I often find much peace in it. When I saw how the same sky looks in its pure form, it left me simply breathless. The same image made me realize that there is still so much to learn about the sky above us too––for example, I thought I saw Venus instead of Saturn in one of the images, (due to the invisibility of the rings), and definitely did not know what to make out of the magnetic clouds of the sun’s wind, whose collision with the thermosphere we can see as the aurora borealis in the northern latitudes.

I believe Noam’s explanation of the sight of the clear night sky helped me understand our immediate cosmological environment much better. Of course Saturn would be Saturn and nothing else––with its beige color––and of course we could not see the rings made of ice and dust without a telescope from this distance! Furthermore, there naturally has to be a scientific distinction between large and small magnetic clouds in the solar wind… It is quite fascinating that these floating regions of enhanced magnetic field and low proton temperature can be observed from Earth. The window into the “everyday life” of our solar system is so present and observable that it is a shame how much we polluted it with our great cities (I cannot help but wonder what Tesla would say about this). I also did not know that the Milky Way could be as observable from the Earth––even as infrequently as Noam pointed. From comets and planets, to magnetic clouds and our galaxy, it is breathtaking to see the sky portray these appearances so vividly and clearly. How is it that not all of us are astronomers, I wonder?

While explaining my fascination with sky observations to a friend here, I realized how much of a problem light pollution represents, especially in our era. The scattering of light in the atmosphere disrupts the contrast between the stars and galaxies to such an extent that we cannot even see our own galaxy. I understand that there is also a lot of cosmic dust obscuring this view, but it seems to me that the artificial light from our planet is a larger issue. It numbs our sight to such an extent that we can become completely unaware of the universe and our position in it. We forget that our place in the solar system and the cosmos is just one of the many worlds out there, and that no matter how beautiful our planet might look like, it is still quite difficult to compete with the specialness of many other planets––with Saturn, for instance, with its dreamy, otherworldly rings around it…

Another thing I recently understood is that comets could be in an ideal light setting much more frequently observable from Earth. I reminded myself that Halley’s comet that comes back every 76 years is just one of the many, and has earned its popularity only due to its great visibility even with a naked eye. I pondered about this comet actually–– its beautiful coma-like tail formation, created due to the melting of its icy structure with the increased proximity to the sun, is quite out of the ordinary, given our usual night sky view. The fact that our ancestors believed in its supernatural attributes that would bring them natural disasters is truly very much understandable. We are afraid of what we do not know.

In a nutshell, I believe two things are important for us non-astronomers: (1) escaping our sky/Universe-numbness by going to a place devoid of artificial light and observing the sky, making connections and finding patterns and (2) understanding at least some of the basics of how our universe works. The truth of the matter is that not many of us will ever be able to fully comprehend all the processes that led to the discoveries that Noam elaborated for us. Nonetheless, it is important to at least understand their importance.

When talking about finding patterns, it is an interesting fact that our mind does it constantly anyways—with that slight danger of false-pattern-recognition in our extreme-logic inclined psychology. I believe this is why many astrophysicists are cautious about confirming theories that cannot be proven, such as those of other dimensions and universes, as well as of those of black holes being a tunnel to them. Or, the everlasting question that is still lacking an empirical confirmation: are there forms of extraterrestrial life somewhere out there? The human mind is so warped by its pattern-search that modern astronomers seem to seriously recognize its limitations. Perhaps we do need scientific proof to find the “objective truth” after all. Do we want to know it though––that, already, is a different matter…

To go back to my fascination with the stars, whose scientific aspect I find very spiritual in itself––Noam truly helped me understand how the history of the Universe as we know it started and came into being. It is the inborn curiosity and pattern-looking human features (together with the experimental proofs thereof) that brought us the knowledge we have today. We should all be our personal astronomers, even if only for a couple of nights a year: far away from civilization, with only a blanket and a clear night sky. Preferably with a telescope too––for an even more wondrous sight of our galaxy and its stars, clouds, and all the other phenomena we might stumble upon.

You can read more about Noam Libeskind here.

Watch a recording of the guest lecture: