My grandfather called me in the afternoon when it first began,

Varstu nokkuð hrædd? Were you afraid?

Ha? Ó, nei nei… Huh? Oh, no…

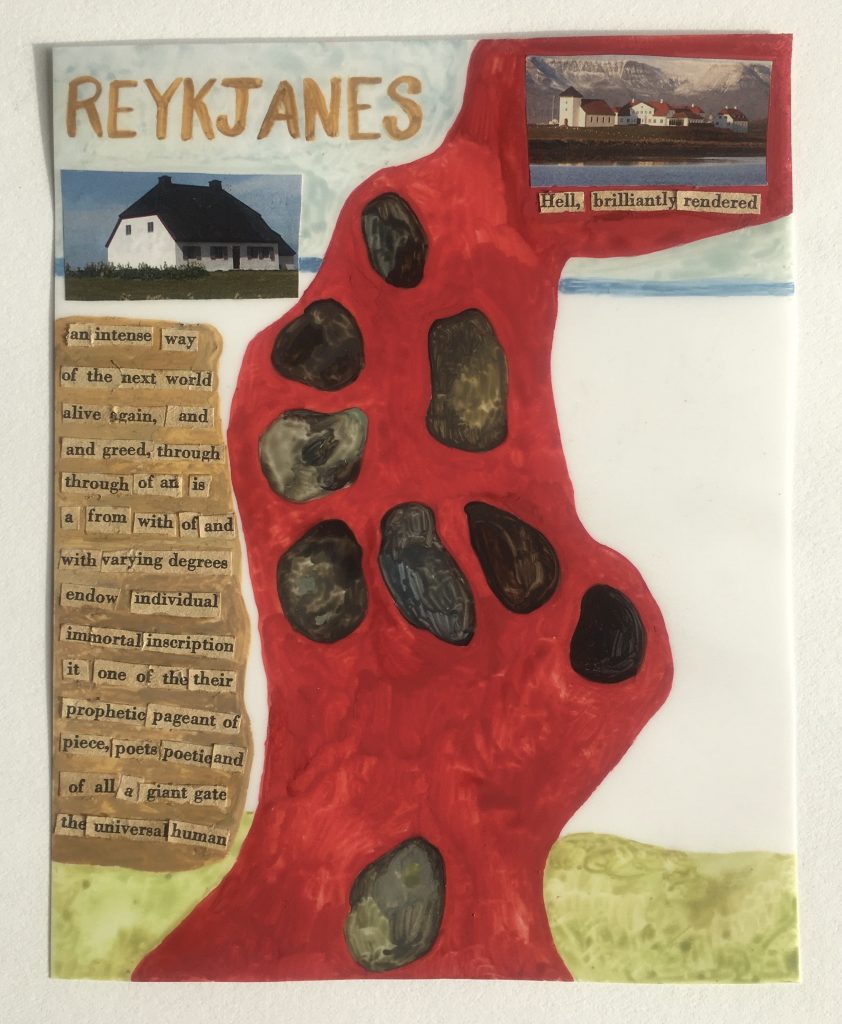

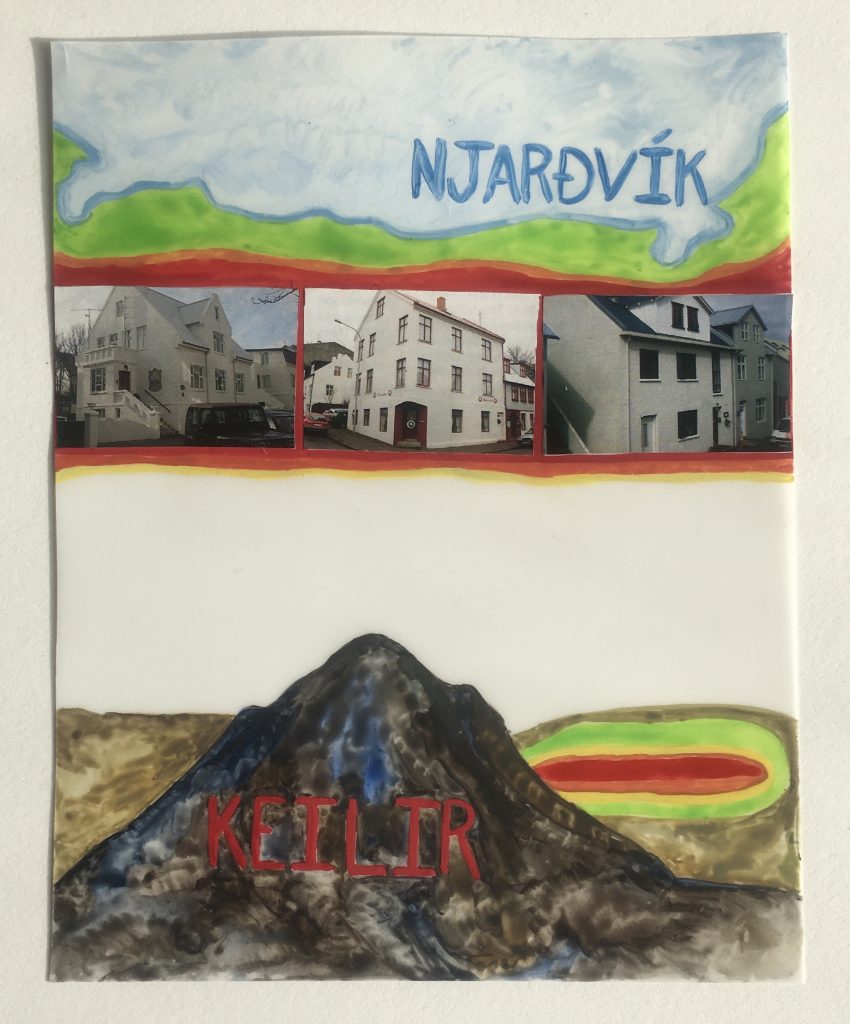

This spring semester, I have been taking my online courses alone in my house in Iceland, a peaceful study spot near the ocean. I live in a tiny town called Njárðvík, which lies on the Reykjanes peninsula. Iceland is an active volcanic island where the forces of nature are colossal. The elements are not passive qualities, lines of pleasant poetry, but fickle tyrants rather, gods.

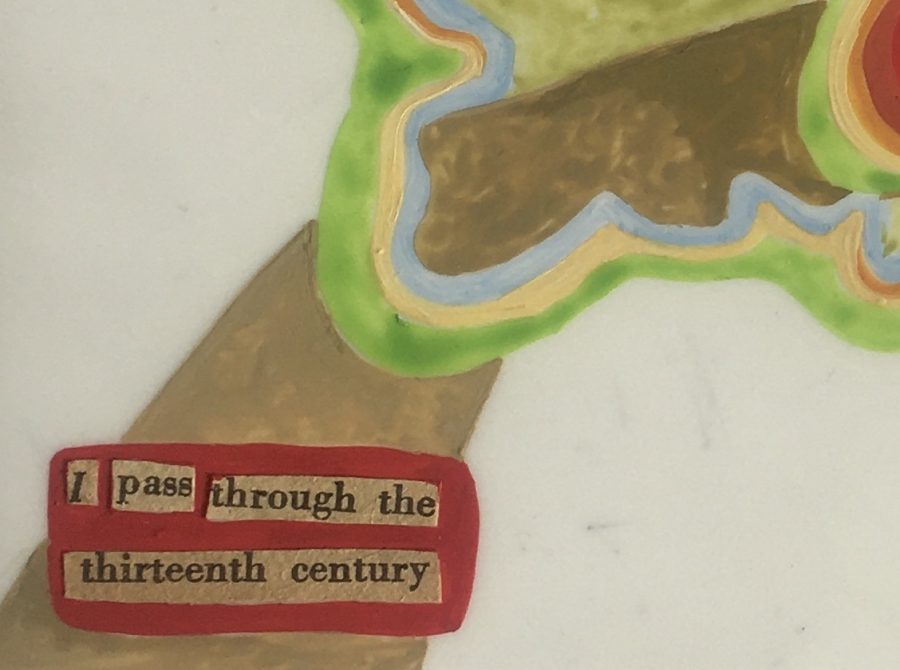

Besides the ocean’s constant rage and ecstasies, this area has been still, movements of the earth dormant within, since the thirteenth century when viking-settled farmers lived in mud and grass huts and disputed over land. Recently something has awakened. And for the past fifteen days, the peninsula has been shaken by over 20,000 earthquakes. Scientists warn of an imminent eruption. Likely no towns will be directly affected by the lava flow if there is an eruption, though there are poisonous gasses to consider. Sometimes with the windows open, the house smells bitter and sulfuric, and I think of the word imminent as it’s repeated in the news.

A magma chamber on the move has been detected between the mountains Keilir and Fagradalsfjall, causing tremors all throughout the region. Though mostly the seismic activity is hovering over the shoulder of Keilir, a dark, pointy mountain about 15 kilometers from my front door. Objects suddenly tremble in my dreams, awakened by an energy which then seizes me before I flutter back into consciousness, groggily check that books are still on shelves and lamps on tables. An earthquake in a Zoom seminar turns me into a bobble head, the computer screen bouncing to the ancient lava-churning waves as I flip through pages of The New Organon. Sometimes I feel awash in rapid oscillations, swept in a vague trembling wave. Other times, the tremors feel spear-head sharp and specific, as if coming directly from under me, a hammer from the center of earth thrown at the soles of my feet.

Iceland sits on two tectonic plates, straddling the North American and Eurasian continents. And the continents are still moving, still splitting from the original motion. Iceland is a land of mitosis, a land responsive to the primeval drift, constantly being ripped in two. It is this tectonic movement which now awakens the volcanic system in the peninsula.

I began responding to the land’s surges in drawings for my class FA103 Found Fragments and Layered Lines taught by John Kleckner. My drawings are usually magnifying glasses, expanding the tiny, the microscopic, blades of grass and dead bees, pebbles and bubbles in puddles. And in this sense of nature I feel one with it, when it rests in my palm and I can finger its ridges or see my reflection in its face. The earthquake is vast, it reaches around me, fills all spaces for the time it endures, like an ancient rhythm not for my ears.

The earthquake, the danger of it, brings out a sense that the environment is happening to me, that it is separate from myself and occurs around and outside and without me. And there exists underneath it a primordial fear, an ancient and true response to the land. Certainly it’s startling, that first instant of shake, the lightning-strike instability that pulses from the earth’s foundation. The feeling bleeds from an instinct of survival; I must resist the land in order to survive, I must be other than nature to overcome it.

Then there’s a sense of awe and fascination. I think about the geological history of the peninsula, the layers of lava flow. The look of this land is old, shaped from the last eruption in the thirteenth century. I look out at the horizon, though not close enough to see lava if the system ever erupts, and envision a terrific red tongue tasting the lava-rock fields, bubbling and mutating the skyline. The familiar textures of my childhood and of the last 800 years, dry moss and dark porous rock, could be swallowed by the earth, the fresh lava hardening into a new topography. I do not so much feel powerless, but taken, even graciously taken, by this place. This doesn’t erase the instinct to separate myself from the action of the land, the subconscious earth-tearing fear. But I can in my fascination respond, initiate my own action and become a part of the system, a part of what happens here. All this activity has awakened some thought of the place.