The term ‘feminism’ has been highly misinterpreted in modern-day society and wrongly associated with stereotypes that do not reflect its nature and purpose as a political movement. To label oneself or be labeled as a feminist is often regarded as a negative thing due to the way feminists are portrayed in the media. Feminism is for Everybody, a course taught by Prof. Dr. Agata Lisiak this fall semester at Bard College Berlin has been seeking to discuss the role, importance and different interpretations of what it means to be a feminist. Through the exploration of various feminist theories, methodologies, and authors, and critical engagement with a range of historical and contemporary literature, film, and visual artworks by women from very diverse backgrounds, students have the chance to understand what feminism looks like from multiple perspectives. I was able to interview two students enrolled in the course, Aditi and Fiona (BA HAST and EPST 2022, respectively), who told me all about their experiences.

In regard to the structure, content, types of texts and some of the discussions these prompted, one of the aspects that stuck with Aditi is the course’s outlook on language. She pointed out how refreshing it is to have no limitation to language, and be able to read texts written by South Asian women, for instance, allowing her and the others to learn and connect with the stories told from all over the world. Another element she refers to is how feminist jargon can be problematic and flawed depending on the culture and language. In some languages, there isn’t a specific word for sexual assault or there is no differentiation between ‘sex’ and ‘gender.’ The consequences of these discrepancies can be significant, given that without an existing vocabulary, how can one be able to fully express or articulate what they have gone through or witnessed, how can they be correctly understood and how can any action be taken? “Many times when you translate from one language to another, the lack of appropriate equivalent terminology can reduce the effect of the meaning of what is being said, it takes away the voice of who’s trying to speak up and undermines the feminist cause,” stated Aditi.

Fiona also spoke about language as a mechanism to promote inclusion. She referred to an assignment the class had to do which consisted of reviewing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and pointing out all the sections where the text wasn’t being gender neutral and/ or inclusive by only stating “His right” instead of “his,” “her” and “their right.” Not only that but for such a prominent document, referenced and followed worldwide to reinforce gender norms, the way it does so is also an issue that Fiona raised. Fiona stated, “Women’s rights were very family-oriented, mainly about children, caretaking, and this is obviously not okay.”

Aditi then talked about the importance of reading texts by queer women and women of color, which highlight how feminism, discrimination, and inequality aren’t experienced in the same way by everyone or to the same extent and can’t be generalized concepts. As a brown, immigrant woman in a predominantly Caucasian land, feeling represented by other successful women with whom she can identify, such as Chandra Talpade Mohanty and Priya Minhas, helps Aditi in how she perceives herself as a feminist.

Similarly, Fiona mentioned how valuable it is to her to be able to use the knowledge, tools, and ideas from inside the classroom and apply them to everyday life. She thinks that when academics align with or influence beliefs, personal values and emotions, this helps students, including herself, develop, grow more confident and understand the place they occupy in society. Aditi sees the topics debated in class translate and materialize into the occurrences of her daily life too. The conversations extend to other settings and aid in the explanation and verbalization of her experiences. Positionality (the social and political context that creates your identity in terms of race, class, gender, sexuality, and ability status, and describes how your identity influences, and potentially biases, your outlook on the world) has been key for both Fiona and Aditi in the process of comprehending the space one has been given, such as in academia or work, and the occupation of this space that wasn’t traditionally theirs.

Furthermore, feeling comfortable with sharing one’s own thoughts and opinions and feeling inspired and empowered by writers and by hearing what each other has to say makes a great difference according to Fiona. She said that, even though the great majority of the class is composed of women, the practice of empathizing and sympathizing is always exercised irrespective of gender.

When asked about the links that can be made between the Feminism is for Everybody course and other courses, Aditi said it aligns really well with her Comparative Politics of Gender and Family course: “The content of both nicely complement each other because feminism is less about females and more about gender.” Thus, looking through a feminist lens is something she does every day without even noticing. Fiona believes that it is closely tied with other Economics courses she has taken at BCB. Certain conceptions and symbolisms present in many of the readings, such as Caliban and the Witch by Silvia Federici, draw from capitalism and other economic phenomena throughout history. This tale specifically addresses the witch-hunt era and how it was marked by both infanticides, as well as strong societal pressure on women to reproduce and have many babies for more economic profit and success in the future. Further, analyzing how everything or almost everything, ranging from the climate crisis to poverty, relates to feminist issues in one way or another was a debated topic that developed from another text, Feminism for the 99% by Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, and Nancy Fraser.

Feminism for the 99% also served as a guide in preparation for a day-long workshop, “New Feminisms, New Questions” organized by Agata for her students and those who wanted to join from the BCB community. The workshop included group discussions and presentations by women from Turkey (Aysuda Kölemen, BCB), Sudan (Fatin Abbas, BCB), Germany (Cassandra Ellerbe, BCB), Egypt (Hana Khalaf, BCB alumna, now FU), Macedonia (Elena Gagovska, BCB alumna, now FU) and Poland (Agata Lisiak, BCB) about what feminism is like in their home countries. Aditi told me her favorite part of the event was a talk by Sarah Banet-Weiser, because they had read one of her works in class beforehand: Empowered: Popular Feminism and Popular Misogyny, where she mentions Beyoncé as a major figure in the feminist movement. Aditi was glad she got to ask Sarah more about popular feminism in person and discovered Sarah even teaches an entire course about Beyoncé.

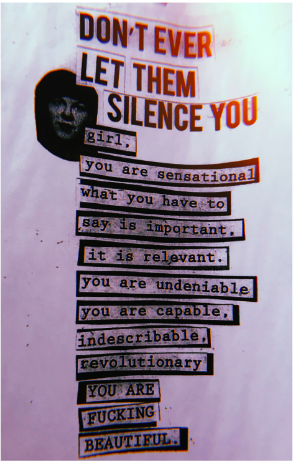

For their midterm project, the students created their own manifestos based on their exposure to other manifestos. Aditi shared that her group remade the burn book from Mean Girls, which in the movie was originally created by The Plastics, a group of popular high school girls who used it for negative purposes, such as gossiping and spreading rumours about other girls. They transformed it into something completely different: a book with a positive message and the goal of empowering girls instead. Some of the other groups’ presentations, like Fiona’s, included combining the theme and format of a text with their own personal narratives.

My last question for both of them was “If you had to pick one thing you think will stick with you from this course, what would it be?” Aditi answered using a quote they were introduced to in class, which she believe sums it all up. It refers to the sense of community, safety, and support that was built throughout these past few months and one of the underlying messages of the course: “In unity there is strength.” Fiona took the opportunity to look back at herself before enrolling in the course and reflected on how her own somewhat cautious presumptions of feminism have changed as she learned about it from all these inspiring women. She now feels like she understands better how she fits into the term ‘feminist’ and in turn how feminism is constantly helping her shape herself.