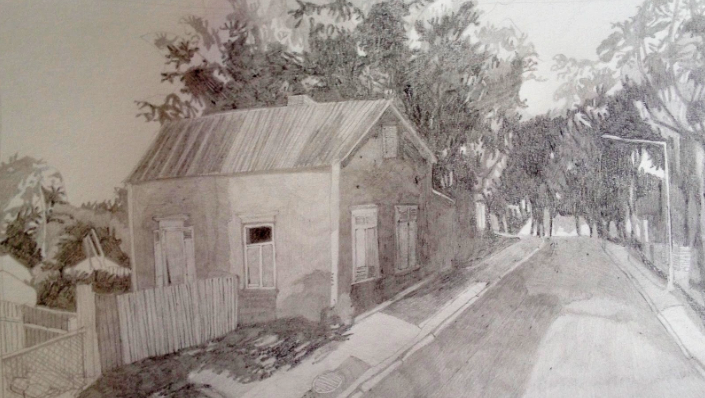

For quite a few years now, I have been drawing houses. All kinds of houses. Walls of multistoreys and factories and wooden sheds, fragments of windows and rooftops, inner courtyards. Almost all of my drawings are based on photographs: movie stills, prints from newspapers and exhibitions — but, mostly, the photographs I took on my walks through the cities I have lived in. My collection started, I think, with a house in a cluster of nameless streets not far from my childhood home. That house looked somewhat like this:

What the image will not tell you is that this house had a moss carpet covering its roof—a sign of neglect uncommon even to that cluster of nameless streets—and a porch painted pink. Perhaps, the colour was chosen to cheer up the woman who lived inside the house. It was her brother who painted it during one of his visits, when he would typically arrange a sofa on the terrace so they could drink tea and watch a movie. Except for those afternoons, I never saw the woman outside; I don’t know what she did when her brother was not visiting.

But it is not difficult to imagine. Once, she positioned herself in her usual armchair next to the window, where her duvet retained its usual cocoon shape. She sat watching the empty street opposite her house, the fence, the garden plot, the stump, the fossil. She went down the pink porch in her thin cotton socks to see the fossil.

The fossil sat propped against the stump. Except for the fact that it was about a meter high, it looked exactly like those from the Natural History Museum her brother worked at: mostly grey, with shades of brown and umber, with sandy bits stuck here and there, distorting its curve. As if somebody had plucked it from deep underneath the ground, where the long-forgotten things are stored. Fossils are remnants of marine animals brought to their current resting place by significant changes in the geological landscape. What were thought to be unicorn horns, for instance, turned out to be narwhal teeth, she thought while carrying the fossil out of the garden gate. By the time they reached the train station, she was straining her back hard under the fossil’s weight. The fossil felt as if it had grown much bigger—or could it be that she had grown much smaller?

The train cabin was empty save for the ticket controller and two old men with a large dog. The controller stamped her ticket the way he always did, and the two old men, having glanced in her direction, each turned to their own window. Only the dog showed some interest in the fossil, but the owner pulled it back:

“Come, leave the lady alone.”

During the ride, she kept glancing sideways to see whether the fossil was indeed still there, the way she would do when she sat next to her brother on the sofa. In both cases, the persistent presence felt strange—as if she had grown a fifth limb, which was her own, and yet felt alien.

When she pushed the fossil out onto the platform, its weight felt unbearable. Yet, on the other hand, she could not remember a time when she felt as light and little as she did now, rolling the fossil up and down the dunes. Surprising, how, even though it had been a while since that long and hot summer she and her brother spent at their aunt’s seaside farm, her feet now took the exact right path. She had climbed that same dune from which they used to watch the road that lead into the town. This was where her brother told her about the narwhals—perhaps prompted by her picking at the shells with the tip of her boot. That summer, she gathered pocketfuls of those shells, miniature cousins of the fossil, and kept them stored safely in a box underneath her bed along with other treasures brought to shore by the sea: glass, dry algae, scraps of love letters that travelled in green bottles. She planned to make necklaces to welcome her parents when they returned to pick her and her brother up. The box grew heavier and heavier, but the road from the town remained empty. When she showed her project to her brother, he told her the love letters were actually cigarette butts. And then, on the dune, he told her that unicorn horns exhibited in the temple they visited with dad actually belonged to huge dead narwhals. She remembered covering her ears and sitting so for quite some time. The wind was strong; she remembered longing for a blanket.

Now, the wind was even stronger, and the water down below was glittering with movement. Come, she wished she could tell the fossil. Come, swim with the narwhals. Yet, as she neared her goal, the whole project began to seem questionable. Even if the narwhals indeed lived in the bay, what did the fossil have to do with those slick and healthy creatures? And why was she so sure the fossil had to be returned? Perhaps she only just hoped to get rid of it. Once she saw it, she could not help but know where it came from, and her feet led her to the place she would have preferred not to remember. To get rid of the fossil, she had to step into that place herself—again, she came not by her own will, same as that long and hot summer when her parents, at that point still together, brought her and her brother to the aunt’s farm “to watch sunsets and fish”. And even though her brother later claimed they were told days in advance, she somehow never quite understood dad and mother indeed would leave. She remembered running along the train platform, trying to keep up with the window of their coupe, laughing even though out of breath. Her brother stopped running first, and she got so angry with him, so angry.

She glanced sideways. The fossil sat next to her, persistently there, though it no longer seemed that big. So they watched the bay, and there was a kind of affinity in the air, the kind she remembered from the nights at her aunt’s, when she and her brother would lie awake in the dark, each knowing the other was not asleep. Without dad’s usual snoring, aunt’s house felt to be buzzing with silence. After that long and hot summer was over, and they returned to their own house, she would still wake up at night, lie still and listen closely—but the only snoring she could hear was her cat’s, in a few weeks to be joined by her brother’s. How quickly he accepted that dad was not coming back. But then, he was always good at seeing things as they were, much better than her already at the age of nine.

Yet, things were different at her aunt’s, in those first weeks without dad. One night, she and her brother sat up simultaneously: there was a tap-tap-tap all over the room. He switched on the light to discover a large moth crawling over the curtain. Without a thought, she grabbed a book from the bedside table and slammed it against the window; she withdrew the book; she crouched on the floor, hugged her knees, and remained so for quite some time, not even crying. Her brother sat down next to her, and so they stayed, who knows for how long. Weeks later, unloading the cupboard to pack their things up, she discovered the book—the one about the jungle, her brother’s old birthday gift from dad—clean, with only the outside of the jacket showing some traces of the moth’s brown powder.

“You should be home, dear,” the fossil said. “Let me take you home.”

So they went home. In the train cabin, one of the two old men sat together with the large dog who had placed its head onto his knee. He was stroking the dog’s skull, and she could tell it felt silky, slightly greased—as if his hand was her hand. She took a snapshot of the dog and sent it to her brother. He replied, almost instantly, with a thumbs-up and a “That is a Canadian Golden Retriever.” To which she replied, “wouldn’t it be great to have a portable reminder for all of the things you ought to pay back?”. To which he replied, “Are you using the I-Notes?” And, after a few minutes, “Or what do you mean?”

The fossil had shrunk to the size of a pebble, and she placed it into her pocket. It shall be gone by the time they reach the town. Right now it is already night, her train is crossing the town bridge like so many other trains I have seen before, and its lit-up interiors seem to float over the dark water all by themselves, as if without a need for any external shell. I would only want to know whether, after the fossil disappeared, the woman managed to maintain the memory of the connection she shared with her brother. Or did it fade away again, the way it did before the fossil came as a reminder? Did she go back to her armchair, where the duvet retained its usual cocoon shape? If only I could climb the pink porch and knock on her door. But I am now far from home, and a few months ago I read about an ambitious building project due to begin where that cluster of nameless streets once was. Perhaps my drawings are a certain circling-around—as if the walls and windows and courtyards were shadow-images of the one house I cannot enter.