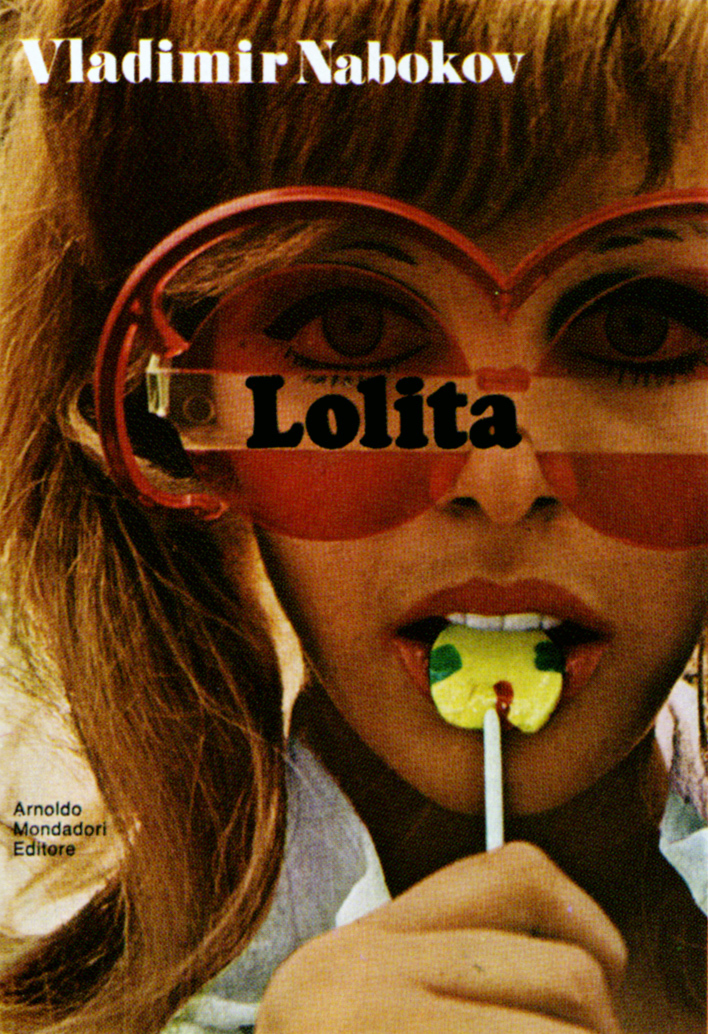

Lolita first introduced herself to me in Portland in July. It was a climate-change-reminding kind of hot, hot as hell, a hot that makes you miserable, cranky, sticky, paranoid in the sun. Portland was a very important interlude on my pilgrimage across America, but the gravity did not strike. Fate’s a funny thing; a method of organizing randomness to which I’ve never subscribed. It puts a timeline on existence, sticks labels on disasters, coordinates every destination into a list, writing the place in bold. As I am an occasional victim of American hyper-future-oriented thinking, the moment, like the bulk of my relationship with Lolita, floated by me. Next stop, San Francisco, where Lolita sat untouched, but smirked and oozed with the knowledge of its power. That perpetual-motion summer I indulged in every corner of America, retethering myself to the country I had left behind for a year, studying in France. I stuck pins into uncharted territory to declare it discovered in my name, retracing the map; déjà vu. It was all a journey with her, really, although I had yet to read the first page. And so I met Lolita on a hot day in a Portland bookshop, but admittedly I had known Nabokov for a very long time.

I suppose we first met in Rennes. It was cold in Rennes, and I whined about it often to my parents back in Cleveland. For my birthday, my father sent me a splotchy, grey and black scarf. It was in one way or another wrapped around me until the smell of spring hovered over the city and the sun asked me to stow away my scarf. My year abroad was coming to a bitter close, a smell to make the moment nostalgic. The scarf rested in a drawer until the night I needed to pack up all my things and go home. I didn’t miss home. At midnight before my early morning departure, I began to pack. To maximize space I unbunched my diaphanous silk scarf, laying it on the floor, unfolding a picnic blanket. The monochrome values of shadow and light unraveled in the splendid silence of midnight, and for the first time, I noticed that the colors were not random, they were not “splotches” but formed a pattern. Faint bands and pale stars created a ghostly American flag. My father, never a man of overt patriotism, had not been aware of this when picking out my scarf. And so, I had spent my year avoiding America with the uncanny symbol of freedom wrapped around my neck. Some living literary symbol, a Greek allegory, the signal of my demise. Irony too rich to believe. Some things can’t be put into perspective until you’ve read Vladimir Nabokov, which I hadn’t yet. But now I am able to sense his presence in the long silks of eerie and nauseating coincidence.

I finally peeled open Lolita on a misty lake in the northern countryside of the Netherlands a few weeks after the purchase in Portland. I had biked with her on my back, she fell only once off the knotted path, only a few granules of sand lost in her spine. The day was placid and still. Ominous, but also blissful, somewhere between heaven and hell. I opened Lolita, and Lolita opened me. The book was gentle and familiar as if I was listening in on an intimate conversation. And indeed, reading it felt like an invasion. Tortuous honesty, heartbreaking and pathetic rawness. All the while, I could taste the subliminal narrative, the under-the-skin story, the aftertaste of a passage. The odd alliteration, a poetic and augural list of school children’s names, rhythmic parenthetical interruption… With Nabokov, all the intimacy and profundity lie between parentheses. He manipulates the flow (interrupted, disturbed by musical parentheticals) to perfectly emulate duality of thought and consciousness. And he too played with my consciousness. I had traveled all this way, covered foreign ground, lived in an alien awareness, and he was always there waiting for a moment of chance to narrate. Now I was reading Nabokov, introducing myself naïvely to his presence, his history. But he already knew me; my time in France had happened with him wrapped around my neck.

It wasn’t a book that “transported you there,” it wasn’t about those coddling sensory frills. Lolita made me more aware of the pace around me, where Lolita was in my hands, where I sat on the beach. The lake mimed serenity, performed scenes of a vigorous and graceful purity. The protagonist Humbert Humbert, too, was at the beach, falling in love for the first time, submitting to obsession, bleeding and broken and burning on the sand. On the beach he completes the diaphanous fabric of his hamartia, its inevitability, the cold, steady fingers of fate. Humbert Humbert is our vile, paranoid, pedophilic protagonist; a relentless and pitiful man who spells love L-O-L-I-T-A. Nabokov tested me, demanded I sacrifice my attention to this grotesque man preying on Lolita and obsessing over the cruelty of his destiny. Humbert Humbert is punished with worldly and quotidian signals of damnation. He perceives all stimuli as markers of his sins, interprets his surroundings as spectators of his misdeeds, forever on trial. Nabokov conducts torture like a concerto, manipulating the thought process, turning me against myself, or against the book, or the sun, or something else. I wanted to distance myself from the protagonist and simultaneously devour his every thought. And the guilt and horror and neurosis built up in Lolita spill over. A dangerous indulgence, I told myself. Don’t lose yourself, stay on the path. I could still be amused by my place at the beach, I could stay a bit longer. I biked away without falling.

That same week I read much of Lolita on a bench in a church courtyard. The church sat humbly in a little Dutch town, content with its years and the randomness of its decay. I sat alone, looking up occasionally to catch an old couple biking aimlessly, or walking their poodle. I didn’t see the irony then, the divinity and the sin. Nabokov did. I read the book in planes, vans, taxis, even walking once; an obsessive and constant movement, dedicated perambulation with all-knowing Nabokov right by my side. The delusion and mania of Lolita is contagious. Nabokov employs rhythmic, alliterative interjections throughout the book to punctuate the beating obsession deep within Humbert Humbert. We hear his compulsion even when he is preoccupied with an outside conversation, hear it over our own protest, our recitation of personal morality. Nabokov writes just as thought progresses, transforms, metamorphoses, akin to my crusade from state to state and through Europe. When I returned that summer to my family in Reykjavík, Lolita followed me.

With cold, mathematical listing (an inventory, a to-do, a wish list…), Nabokov charges the interior dialogue with an eerie vitality while reducing that of the exterior to floating wholly ephemeral and frivolous. The real, spoken, tangible conversation never leaves the ground. Then what is real? What resides simply in the mind of this madman? The paranoia and agonizing coincidence that plague our wretched protagonist make us reevaluate all we assumed to be based in reality. Doubt, like movement, fails to cease. Humbert Humbert rewrites his life to make sense of it. His literary experiences, so full of obvious symbolism and palpable foreshadowing, are the manifestations of his guilt. Humbert Humbert feels enslaved by fate, but he is prisoner to his own obsession. Every sentence begins with L, every thought orbits her youthful image, every book, magazine, recipe, list, letter, a poem of Lolita. He orchestrates his narrative, revises, and manipulates history, rewrites road signs to point him towards the lake, because nothing can be his fault if fate was in control, if fate guided him towards the lake and to Lolita, as I was driven to the lake to witness it all. I see my past in Nabokovian terms now, my history recolored in his vision.

There is hardly anything in this world I do not file under the doctrine of pure coincidence or the madness and nothingness that make life lack all formal purpose. There are no spectators, no moral jury. Guilt is not a catalyst for change and nothing is set in stone. Humbert Humbert never releases Lolita, never stops loving her. I submit most moments of my life to the concrete certainty that there is no such thing as fate. My sister wanted to go to the lake that day, my mother suggested I walk to the church. I believe destiny is constructed by those who lack purpose. Nobody will advertise the way to Mecca, nobody will model the savior. And yet, I cannot deny the extraordinariness of studying sin in courtyards of god, venturing to the same crime scene as the literary villain I read about, and strangling myself with patriotic propaganda. Then, I can hear the narration of Vladimir Nabokov like Rod Serling introducing an episode that will surely shake my firm, agnostic resolution, even if only to recognize the literary moments of life.

I’ve tried to read Lolita. Can’t say that it is my favourite book, but it definetely has a great artistic value. Though I couldn’t read it to the end, I’ve read only the first book…I couldn’t read more, since my younger daughter was of the same age as Lolita… But now I’d like to read it it to the end.

Thank you for a nice article