Care is a political phenomenon and the crisis of care is beyond just the denudation of these public structures: it is actually a deep-rooted attack on working class life-making.

Tithi Bhattacharya, March 2019 interview with Jacobin Magazine’s “The Dig”

On Monday, February 26, warning strikes and protests erupted in Germany from across the public sector. Those taking to the streets included teachers, nurses and park administrators, causing school and daycare closures and slowdowns in hospitals and government offices. I found out about the strikes the weekend before they happened when my flatmate scrambled to find childcare for her 8-year-old son. Strikes and protests continued throughout the week. On Wednesday the 28th, 10,000 strikers marched from Potsdamer Platz to Alexanderplatz to join a rally of librarians, police officers, firefighters, and state government employees calling for higher wages and better working conditions. The strike brought attention to a country-wide crisis in the fields of education and healthcare. In order to find a long-term, equitable solution to these problems, broad coalitions of workers and people who stand in solidarity with education and healthcare workers need to mobilize. As students who take advantage of German public services, it is imperative that we join German public sector workers in their struggle for dignity.

A Marxist feminist definition of “care work” includes most of the workers who took to the streets in February 2019. These professions include those that fall within our traditional understanding of “care” as well as all other professions which facilitate the reproduction of our lives — what Tithi Bhattacharya calls “life-making.” While police officers were a part of the strike, police officers are not care workers. I, along with other advocates for a radical re-imaging of policing, observe that policing in its current form primarily serves to protect private property. Generations of organizers have documented how police officers systematically over-police, harass and kill people in historically marginalized communities, particularly black communities; officers rarely face retribution for the cases of violence that are reported, and hundreds more are estimated to go unreported. Care professions that allow for the reproduction of our lives include education, healthcare, emergency response, the maintenance of public parks and libraries, and public transportation. These care professions are under continual attack by neoliberalism — a set of political values that prioritize the free market and privatization over investment in public and social goods.

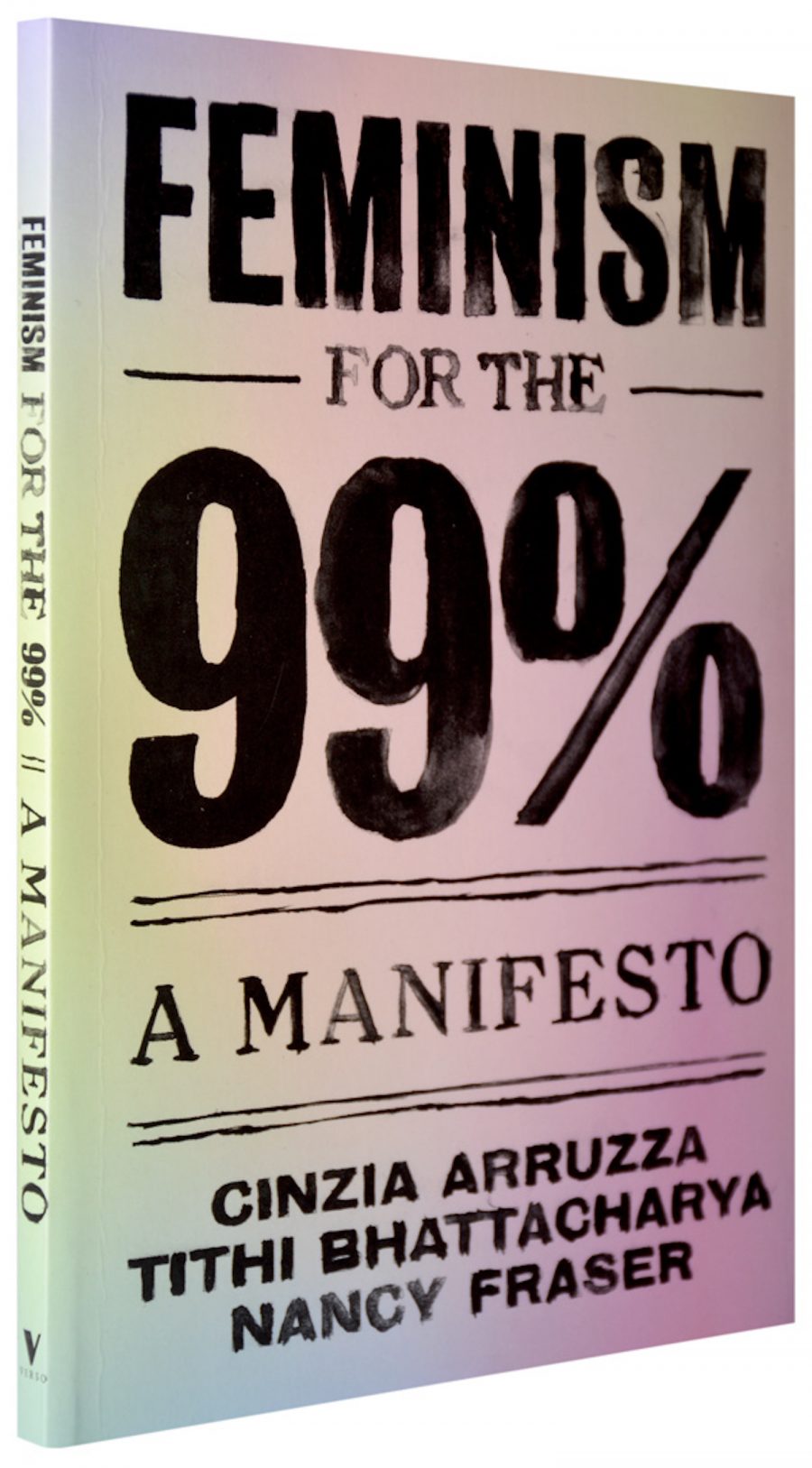

It is not only morally but politically imperative that students join in the struggle to protect the conditions of their labor. German and international students who work as apprentices, interns and trainees are directly benefiting from this strike as they will see a fifty euro per month pay raise as a result of it. But these student groups will not be the only ones benefiting from a better-paid public sector. Unemployed students and those who work in the private sector are also impacted by the quality of public service jobs available in Germany. German citizens and immigrants alike depend on hospitals, public parks, and emergency responders. Some students rely on kitas to accommodate their children during the day, and many more consider entering the public sector after graduation. While higher wages and better working conditions certainly incentivize workers to enter into care professions, like teaching and nursing, or to work in libraries and government offices, higher wages do not only serve the function of perpetuating work in this way. As theorists Nancy Fraser, Tithi Bhattacharya, and Cinzia Arruzza write in their manifesto Feminism for the 99%, just wages also allow workers access to their means of living: food, clean water, healthcare, clothing, reliable housing, and leisure.

These basic human rights, under capitalism, have been commodified. Housing, clean water, and healthcare either aren’t provided by the state or have become prohibitively expensive for working-class people. Most schools and daycare centers are still financed as public goods, but in some places, especially in the United States, the proliferation of charter schools are undermining the provision of what has come to be considered the basic human right of education. And so care workers, day in and day out, find themselves on the ground floor of the international class struggle.

German strikers recognized that their protests occurred during a time when public sector workers all over the world are agitating for better workplace conditions. A striking teacher interviewed by the German World Socialist Website (WSWS) referenced the massive teacher strikes that have been happening across the United States since 2018: “They have our solidarity. They are paid even worse than us and education in the US depends even more on money.”

Care workers, broadly defined, face the brunt of an increasingly unequal world. In my hometown in Tennessee, public library employees across from a public park where homeless Nashvillians live provide computers, career advice, entertainment, shelter and even bathrooms to this vulnerable population. Meanwhile, developers seek to privatize the park, pushing unhoused people farther and farther outside of the city center. Across the ocean, a devastating blaze in London’s Grenfell Tower block killed seventy-two people in 2017. Housing activists told The Guardian the fire resulted from a “combination of government cuts, local authority mismanagement and sheer contempt for council tenants and the homes they live in”. On the ground at the scene were hundreds of emergency responders, both firefighters and police officers. School teachers in Germany also report being ill-equipped to accommodate the needs of students with a background of forced migration. A striker told WSWS, “This situation [of underfunded schools] has been made even more difficult with the inclusion of …refugee children” who aren’t able to receive specialized language learning and counseling services in overcrowded classrooms.

On March 2nd, trade unions and the Tarifgemeinschaft der Länder (TdL) — the Collective Bargaining Community of the German States, which represents German government employers — came to a controversial agreement that prohibits public sector workers from going on strike again for the duration of the 33-month contract. The crisis of care workers in Germany and around the world is far from over. After Spring Break, Die Bärliner will publish an interview with students in the Spring 2019 “Future of Work” course and its teacher, professor Boris Vormann, to see how public sector strikes and international solidarity play out on the BCB campus.