What connection can be made between Socrates and Marx, men separated by over two thousand years, but both hugely influential on the history of Western civilization? Are they both intellectuals? Certainly. Both philosophers? Possibly. Both revolutionaries? Not necessarily.

The question that ECLA gathered on November 18 to discuss was their relevance for contemporary controversies over the family and individual rights.

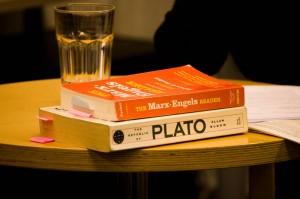

The organizers of the event, Professors Ewa Atanassow and Ryan Plumley, publicized the “Marx v. Socrates?” event as a debate on their respective positions. With these texts at our disposal—Friedrich Engels’ The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State and Book V of Plato’s Republic—we arrived at interesting conclusions about their pertinence to current debates.

Both promote the equality of women and men, essentially through a destruction of the family structure as these figures knew it (and, for the most part, as we know it today). What are the limitations of Marx’s and Socrates’ accounts, and why might we be hesitant (or not) to call them feminists? Furthermore, what do similarities in their declarations suggest, given that they are separated by a span of two thousand years?

Before moving forward, we must consider if the arguments that have come down to us can even appropriately be ascribed to Socrates and to Marx. As Ewa noted during the discussion, the two texts analyzed both make the claim of representing an authoritative voice. The text by Engels was published after Marx died and claims to be a synthesis of his notes on Lewis H. Morgan’s anthropological text on clan structures: Ancient Society.

The authenticity of Plato’s representation of Socrates in The Republic is even more doubtful, such that the claims made in Book V suggest that Plato may be producing an image of Socrates that calls itself into question and bears an ironic relationship to historical reality. Nonetheless, the ideas that we have of Socrates and Marx are substantially informed by these ambiguous records offered by Plato and Engels.

In the first instance, two quotations from these texts appear to have a certain resonance. Engels states, “with the passage of the means of production into common property, the individual family ceases to be economic unit of society […]. The care and education of children becomes a public matter.

Society takes care of all children equally, irrespective of whether they are born in wedlock or not.” And from Plato (through Socrates): “‘all these women are to belong to all these men in common, and no woman is to live privately with any man. And the children, in their turn, will be in common, and neither will a parent know his own offspring, nor a child his parent”.

The destruction of the family as a unit of private property is a shared element in both theories, but while Engels advocates the public care and guardianship of children, Socrates describes a condition of common ownership of women and children by men.

Further differences also emerge from a similar basic proposition in both philosophies. For Engels, the end of the family’s link with private property creates the possibility of a voluntary monogamy based on feeling, or true “sex love” as he puts it, as opposed to the hypocritical structure of the bourgeois family, devoted to the reproduction of children and relying indirectly on the institution of prostitution.

For Plato, the end of the private family unit dedicates all citizens to the public good, including the efforts of women themselves, who have “the same nature [as men] with respect to guarding a city” except with regard to differences in physical strength.

What a comparison between these two texts ultimately showed is that any debate on the arrangement of the family is also a debate on the structure of society, on the rights of individuals, and the relationship between those individual rights and the demands of reproducing and raising children, as well as the connection between sentiment and political order.

by Michael David Harris (AY ‘12, USA)