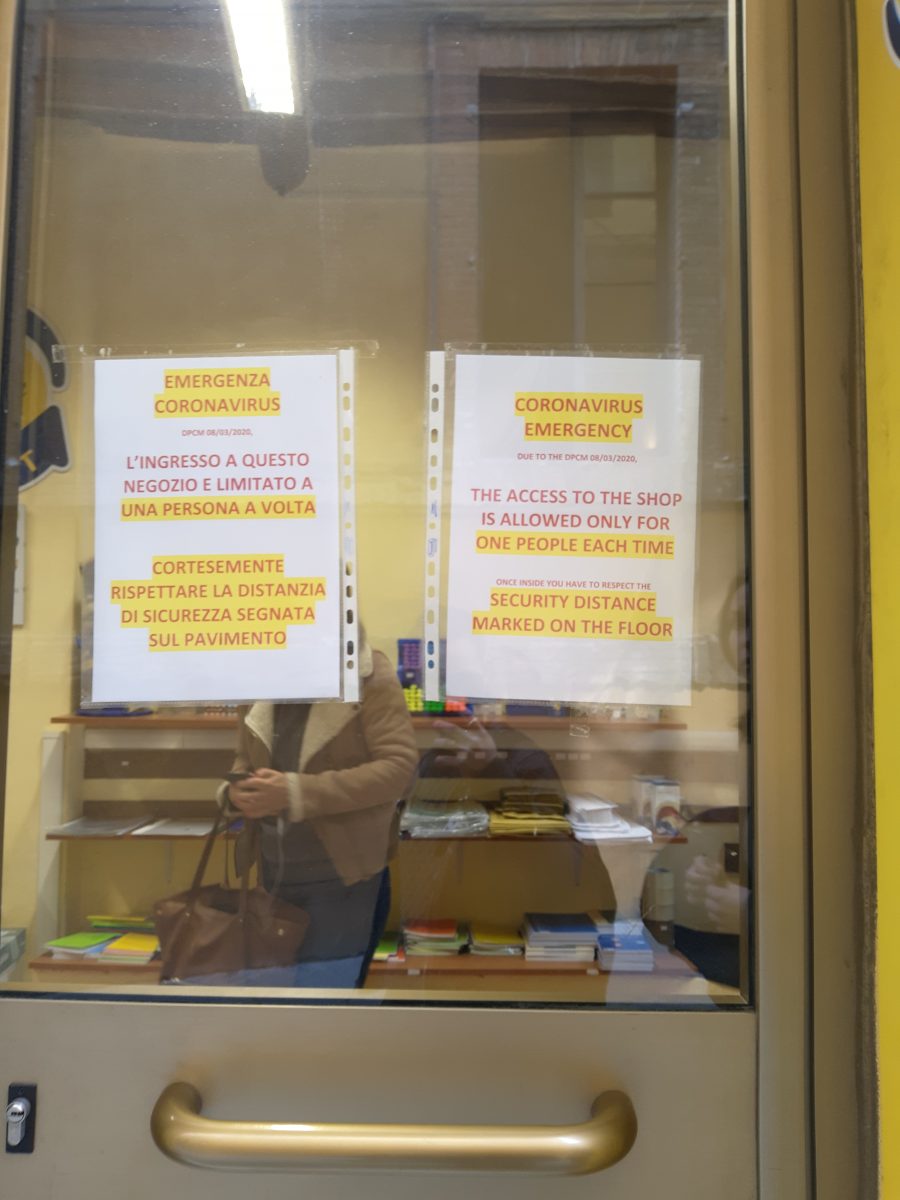

Late on Monday, the 9th of March, the Italian government placed the entire population of approximately 60 million people on lockdown. This move extended the partial travel ban on the northern regions of Lombardy and Veneto, which forbade travel for reasons other than work, medical, necessity or returning to residence and required people to fill out and carry a document stating their purpose for movement. Abuse of the system results in a fine. As well as the travel ban, many public gatherings including funerals and weddings were banned, restaurants and cafes began closing at 18:00 and a one metre distance between individuals in public places became obligatory. Late on Wednesday, the 11th, the government intensified measures by closing all shops besides pharmacies, grocery stores and edicole (small shops that sell bus tickets, cigarettes and provide printing and copying). On Thursday the 12th, Angelo Borrelli, head of the Italian Civil Protection Department which deals with emergency events, announced that the same form needed to move within Italy would be required for pedestrian traffic, which in effect limits people from being on the street for any reason other than necessity. [*1] We are in effect, confined to our houses and apartments.

These actions mark a critical and pivotal moment in the story of Western democracy, specifically in the interconnected world of the 21st century. Never before has my generation—a generation that has grown up in the so-called globalized world of “time and space compression” [*2] in which everything has become within our grasp—faced a situation where our individual liberties were curtailed for the good of the many. I speak, of course, only for those of my generation who have grown up as I have: privileged by my race, class and passport, to reap only the benefits and none of the shortcomings of a globalized world.

That is to say, finding myself suddenly in the situation where I am forbidden to move beyond the community I find myself in and where daily activities are put on a substantial hiatus, I have had to face for the first time the question of how highly I value the good of the many compared to my individual liberty. Not only has travel within Italy been forbidden, but shops, libraries, museums and all public spaces have been closed. Streets and piazzas are eerily empty and the usually jovial Italians keep a wary distance from one another. The one metre safety distance between people in those shops that remain open is enforced (including for myself and my roommate, despite the irony that, sharing a living space with her, if either one of us contracts the virus, we both will). My classes continue in online mode and as more countries begin to implement similar strategies, the end of the lockdown (officially set in Italy for April 3rd) begins to feel less certain.

As much as the restrictions may chafe—especially for a famously cavalier and rule-bending people as the Italians—most individuals around me seem to have understood the gravity of the situation. Whether this is from an understanding that these measures are meant for the good of all, or because of personal fear (I would like to believe the former especially amongst people my age who worry less about contracting the disease for their own sake than about spreading it to those who are more likely to be harmed by it), people are gracefully giving up their individual liberty for the interest of the nation. The University of Bologna has done an impressive job of setting up online classes for something around 95% of their entire program up until now with plans to be 100% active online by the 17th, and, with a few exceptions, actual studies are little disrupted. Of course, the inconvenience for those who are graduating is increased by the fact that all gatherings have been indefinitely postponed. More generally, people are finding ways to show their solidarity within one another. In Siena, the streets come alive at night as people sing from their balconies eliciting a feeling of unity at the same time that social distancing takes its toll on the psyches of 60 million Italians.

Now, anyone at all familiar with a liberal arts education must be aware that questions such as these, dealing with individual vs general liberty, ethics of means or ends, and civic responsibility, are ones we deal with on a regular basis, and I am happy to admit to being a staunch supporter of the belief that individual liberties should play second fiddle to the good of the community, nation, and planet—in theory. I am thinking particularly of the “harm principle” as articulated by John Stuart Mill in On Liberty. In the first chapter, Mill describes how democratic self rule does not imply that each person [*3] rules themselves, but that each person rules all others: “The ‘self-government’ spoken of is not the government of each by himself, but of each by all the rest” (8). This implies mutual responsibility in the actions of each person over all others and brings Mill to the harm principle, which roughly can be boiled down to the idea that the suspension of the liberty of any person can only be justly done to prevent harm to others: “…the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant…” (14) To end the chapter Mill speaks of the three essential liberties that must be present for a society to be free: the first liberty is that of the liberty of the individual in his thoughts and beliefs, the second is in his actions as long as they do not harm others, and third is the liberty of assemblage of different persons and their combined actions as long as they do not harm others (17). Taken as a whole, Mill makes a case here which I think stands up well in our current circumstances. Although free movement is seen as one of our most fundamental liberties, it has begun to present harm to others and should thus be curtailed. Mill offers us a way to view this infringement of our individual liberty in a different light; one which shows that it is our responsibility to change our habits for the good of all.

However, it has been a long time since any remotely similar curtailment of rights was asked of us in Western democracies. These moral arguments become much harder to swallow in the face of actual curtailment of rights, and I will readily admit that my first, and indeed second instincts, were to flee from such measures, even while faced with the understanding that it is the wrong thing to do in such a situation, both because of the potential for spreading the disease and also because such an act would undermine the civic duty which has been asked of us. It becomes not only a practical question of the containment of the pathogen, but a question of ethics and responsibility. As Italian Prime Minister Mr. Conte rightly put it, “We all must give something up for the good of Italy.” But this is not something my generation has any real experience with. Too young to remember 9/11 properly, too naive in the ways of the world to understand the full ramifications of the Financial Crisis of 2008, we have grown up with the world at our fingertips and no real checks on the belief that we can do as we please, when we please.

We all, and I speak now of the wider world, have also grown blind to the fragilities of our interconnected system. Just-in-time production [*4] only works when people are not in quarantine, the stock market only functions with a reasonable amount of faith in the system, citizens only remain safe when their governments act responsibly.

COVID-19 provides us with an immediate threat to our way of life and our individual liberty on such a globalized scale; however, it does not represent anything wholly new. The crises brought on by global climate change pose the same existential threat but have somehow not managed to spark our concern even as their long term effects are likely to devastate our ways of life more than any single pandemic. This is in no way to mitigate the effects of the virus, only to bring to light that COVID-19 is eliciting actions in us that need to be considered more widely. Mr Conte has gone farther than any other democratic leader to call his nation to heel—albeit at a point where the situation was already likely out of control—a move which I believe was made rightly and which required a type of resolve which is likely to become more necessary in the years to come.

Too long have we, the privileged, taken for granted, and in some cases abused, the rights which have been granted to us. As terrible as it is, COVID-19 may be a wakeup call for those of us who have never had to experience “giving up something” for the good of our nation or our planet. It is time for us to face the reality of individual rights versus the good of our community. Because even after COVID-19, there are likely to be more such events—viruses, natural disasters and wars—which will mean blissful ignorance and the belief that all will be well with no modifications to our behaviour, can no longer stand.

Rebecca is a third year student in the EPST program. She enjoys drinking coffee and going on overly long walks in random places (both activities are preferable with her good friends who mean almost everything to her). She is deeply uncomfortable staying any place for too long and loves train travel and listening to indie music.

Notes

[*1] Food and medicine shopping, work, returning to residence, caring for family and exercise (provided the one metre safety distance is maintained).

[*2] A term coined by David Harvey in his 1989 work The Condition of Postmodernity which implies a shrinking of the world due to technological progress

[*3] Mill was not the most inclusive or forward-thinking of people, and so went with “man” not “person” but for sake of my argument I have been more general.

[*4] A production system meant to increase efficiency by decreasing on hand inventory, and instead relying on the supply chain to deliver necessary materials at exactly the needed moment.

Rebecca, I am very proud of you and your mature outlook. I wish that everyone in your generation could read your blog.

Thank you Rebecca. A thoughtful and cogent response. Stay safe..