I have never been interested in politics. Writing about cinema, animals, food and city traffic, I always considered politics as a predictably double-dealing (although well-paid) field, which never appealed to me. However, my 2012 autumn happened to be extremely politicized.

This past October, there were parliamentary elections back in Ukraine, where I come from. I experienced all the aspects of the expat election process – from the (a bit too) ceremonial voting in the Ukrainian Embassy in Berlin, to a pathetic meeting with compatriots, followed by an intensive three-day browsing of blogs and websites for the latest news from my homeland.

Even though Ukrainian elections got a certain coverage in German newspapers, my university classmates and the local media focused mostly on the U.S. presidential elections. Before this year, I couldn’t say for sure which of the parties had a donkey and which an elephant for a symbol. Today, I can easily list the so-called “swing states,” understand the meaning of the “magic number 270,” and briefly sketch the portrait of a Democrat or Republican voter.

My basic general acquaintance with the U.S. political system started with Prof. David Goldfield, who lectured in October at ECLA of Bard on the topic of the U.S. election campaign 2012. Being an expert in the areas of “American South,” “Race Relations,” religion, and political culture, our guest provided a concrete analysis of the strong and weak sides, together with the perspectives of both candidates.

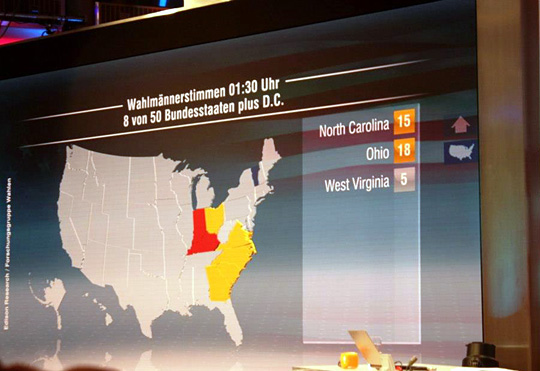

According to Prof. Goldfield, elections in the U.S. are quite predictable: since the Americans can vote in advance, one can say with a high level of probability which state will be painted blue and which red on the election map. Yet, there are also those unpredictable states, in which the difference in preferences is very tight, and which are called swing states. There are about 6-7 swing states which can influence the final results and, in Prof. Goldfield’s opinion, it’s Ohio that is decisive for this round of elections. “No Republican has ever been elected president without winning Ohio. If you hear on the TV that Obama got Ohio – it’s pretty much all over for Romney,” explained the lecturer.

Visually, the U.S. election preferences map looks dissonant, which also confused me in 2008: the map was mostly red, but still Obama was the winner. The reason for this is that the central states are not that inhabited and don’t have many electoral votes, while a highly populated, totally democratic state like California may bring Obama 57 points at once.

Portraits of typical Democratic and Republican supporters are also clear enough. Obama gets most of his support from urban citizens, irregular church goers, immigrants, sexual minorities and young unmarried women. This latter category has been voting for the democrats since 1996 – in Prof. Goldfied’s words, “Women loved Bill Clinton and he loved them right back” – and will stick to its vote due to Obama’s reproductive rights policy.

What about devoted Republicans? White evangelical Protestants from rural areas and small cities, older married people with conservative values, middle-class workers. Seems like a good basis, but it’s only a first impression. The fastest growing religion in the U.S. is none and Protestants have the most to lose. Older people may just be unable to vote by the next elections while the number of minorities keeps increasing.

The only great advantage for the Republicans is the political passivity of the young multicultural electorate. For example, before the elections, David Goldfield personally explained to his students the price of a single vote in a swinging state. Nevertheless, he ended up hearing ridiculous reasons for not going to vote – like parties, too much beer or just bad weather. With its enthusiastic voters, 2008 was an unbelievable exception, but since then things have gone back to the old way.

After Prof. Goldfield’s lecture, ECLA of Bard students had a typical American debate get-together in the Student Centre – eating snacks, watching the debates online and hotly debating among ourselves, while also joking about Romney’s legendary “binders full of women” – a phrase which spread around the web within a few hours after the second of three debates. A pre-election debate is a rather interesting TV genre, which doesn’t change the line-up dramatically but has high ratings and is meticulously analyzed by respectable media resources. Watching the debates on YouTube a few days after they actually happened, we already had access to analyses of both candidates’ speeches posted on the web, which gave us more space for argumentative discussion.

On election night, ECLA of Bard students and administration representatives were invited to Deutsche Telekom for a late night gathering with German and American politicians, media stars and celebrities. Upon arrival at around midnight, I could find only political symbols of the Republicans and Romney badges left over for distribution: Democratic souvenirs had been distributed extremely fast hours earlier. The large majority of guests raised toasts for Obama while eating from the truly inexhaustible hot dogs and donuts.

It obviously wasn’t a glorious day for the Republicans in Berlin. With every new blue-colored state, the majority of the audience burst with applause. In the case of triumph for Romney, there was only a tiny group to shout out in his support. Democrats were confident of their success, and if the Republicans had managed to win, political fans (which at that point looked more like football fans) would have ended up in the streets, rioting.

Not this time, however. I discovered the final results via the Facebook stream, on my way home on the early morning S-Bahn. ECLA of Bard students – American, Asian and European – spent the night watching live streaming and drinking celebratory champagne. Many of them didn’t manage to sleep and went to classes drowsy, but happy. There were no disputes – everyone supported a single candidate as the only possible right decision.

At the same time my Ukrainian-speaking web circle is still filled with political miffs and insults among peers. Is it because we choose one out of five-six candidates instead of two? Could be. But since the Orange Revolution in 2004, which merged Ukrainians around the idea of fair elections, the spirit of unity has been hopelessly lost, and I can’t imagine all the students of my university (well, faculty) in Kyiv celebrating the victory of the same candidate so unanimously. For the whole night. Alle zusammen, as we did it here, in Berlin.