This story is based on true events.

Mrs. Rudikoff had an unsettled and frightened look on her face when she left our apartment in Spanish Harlem that evening. She also appeared to be full of judgment; mostly towards how my brothers laughed instead of how they should have taken pity on her when she said she felt attacked. Also, she probably was judgmental because she knew when she would tell her daughter that there were 40 tiny mice running on the floor in the Manhattan complex her daughter would scream. Her daughter would go on to say, “Those Devyatkin boys are wild. How could Vita allow such boys, so young, to have a pet snake in such a small apartment in the city?”

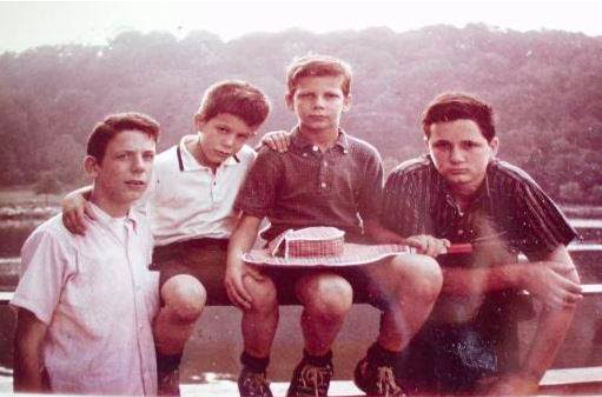

Mrs. Rudikoff came over that Saturday evening for tea and cookies as she often did. I was twelve at the time, my brothers were younger and more childish. They made dirty jokes and prank calls to strangers they found in the yellow pages. In my free time, I liked to follow strangers on the street. I’d walk behind them and see where they would take me. I laughed when one of my brothers made a dirty joke though. Mama asked us to compose ourselves when older guests were around.

When Mama sat Mrs. Rudikoff down for tea, my brothers and I went on with our Saturday night routine. Mama would make us read for three hours every day; that evening my brothers were reading Pushkin and Tolstoy. As they read, I played violin for them.

As I played violin and tickled the tiny strings, I watched Lucy, my pet snake at the time, move in waves. She hissed a little as if she were creating a tune to move in sync with; almost rhythmic. At this moment, I noticed her beauty and elegance for the first time. I got her as a birthday gift because I told Mama I thought it would be a charm for girls in school; a boy with a pet snake, he must be a little dangerous.

I hadn’t looked at Lucy in a long time. I also hadn’t ever watched her so closely. I noticed there were more mice in her cage than usual and her body was slender. She had stopped eating and the mice began to multiply.

I noticed a tiny hole in her cage. It seemed large enough for the mice to escape. I wondered and worried if Mama and Mrs. Rudikoff would be surprised by a swarm of tiny rodents. I ran to the cage with big bug eyes to look and count how many mice there were. My brothers put their books down. I heard Mrs. Rudikoff laugh in the living room. Her laugh soon after turned into a raging scream then a low pitched howl then a smirk of disgust. Mama apologised for one minute without breathing. She couldn’t stop saying how embarrassed she was.

I ran out with my brothers and Lucy. We laughed but also felt a tickle in our spines; the amount of mice on our living room floor was unheard of. They began to take over the shelves and climb into the old china cups. I didn’t understand where they were hiding before.

Papa came home and laughed with us. Mama felt uneasy, she knew Mrs. Rudikoff would gossip that she was a no-good home keeper and that she didn’t raise her boys to know respect. Papa grabbed 40 mice, one at a time, by the tail, and slammed their tiny bodies against the bathroom sink. The sound was like the ticking of a clock, kind of like our old grandfather clock. Except this sound was slower and not as nice to hear, with a muffled crack. The dead piled up. I asked papa why he killed all the mice. “They could never survive in this city. They wouldn’t even make it in Central Park,” he answered.

New York 2009

I always thought that my idea of family and being a collective unit was tainted by metropolitan life. Gritty bodegas that only purposed alcoholics, laundromats full of gross men and complexes full of strange neighbors. Living in New York City, I often thought my family wasn’t how it should be. It didn’t function as well as it could; we didn’t communicate how we should; we didn’t feel the pace of life and growing up in a normal temporality. Things were to be a hell of a lot different if we had a huge garden in the back of a two-story house with a few house pets. But we had a fire escape where we grew basil and coriander and where Papa would go to smoke when he and Mama would fight. I guess I thought space didn’t allow for a small community which was my intermediate family. Or even my extended family. My extended family lived in the Meatpacking District, Spanish Harlem, Chelsea and Hell’s Kitchen whereas we were based in the center of stroller-ridden, coffee-sunken, rent-soaring, screaming Flatbush, Brooklyn.

A moment that grounded me to the normalcy of family life in this urban but secluded Brooklyn neighborhood complex was a weekly routine my family shared on Sunday mornings. I remembered this Sunday in 2009 a bit more vividly than most Sundays. I awoke in my loft bed to the smell of freshly french dripped coffee into my bedroom. My brother walked in with a cup of coffee and stood by my bed, almost bragging that Papa let him have a cup. I went into the kitchen to get my own cup of coffee. The coffee which I thought was warm was brewed steaming hot so when I drank it there was a hiccup in my throat; a bulging burn. I gasped for air. ‘Morning Miss Lovely. You ready to go to the spot?’ I nodded, left the coffee to cool and ran to my room to throw on a dress. My brother was already dressed in the living room counting quarters. ‘Papa, you got another few quarters? I don’t think it’ll be enough…’ Papa walked into the living room and said he had enough. We left the apartment, walking down eight flights of stairs running into a neighbor who grumpily wished us a good morning. The landlady stopped Papa as she always did. ‘Dimitch. Come in for a cup of coffee. What are those no-good kids up to today…’ Papa assured her he’d come by later. She looked older today, even with just one-day passing I noticed the wrinkles had dug deeper into her skin. ‘Sweetheart, you need a few more quarters?’ I said we didn’t need it but thank you anyway.

We got to the laundromat spot around the corner. The smell of fabric softener whiffed in the room as we walked in. The laundry machines were groaning and shaking. I ran to the end of rows of laundry machines to two empty ones. The coffee must’ve kicked in that moment. I smiled from my achievement of finding empty ones when there usually weren’t any unused upon arrival. We loaded up the machines. The quarters jumped and ticked into the machine-like clockwork. Papa was happier than most Sundays. ‘Good job babe, you found a buck in a million.’ Some man smirked at me. That wouldn’t happen in a laundromat in Chelsea I thought. Papa pushed me a bit aside from this man. I lost my focus in the whirlwind of clothes when the machine turned on and the foam started to bubble up like a cauldron. ‘Now we just sit.’ I asked Papa for more coffee. Instead, he got us Coca Cola from the bodega. My brother laughed from the sugar high, Papa congratulated me on my first A in school. He said Mama would be proud. I sunk into the moment. A collective elation. Spiraling laundry soon that would be soaking clean. There was nothing left to do that day except go play frisbee in the park. I felt the closeness.

Sonya Dimitrievna Devyatkin was born in Moscow, Russia. She grew up in Brooklyn, NYC and moved to Germany when she was 12. Published for the first time when she was nine years old, she has been writing since she was five years old. Stayed tuned for her new book coming out.