In the spring of my first year at Bard, I took my first studio art course since the beginning of high school. I was never skilled at drawing, nor did I ever devote the time to develop skills in painting, so I figured that taking a sculpture course wouldn’t be the most difficult medium to practice in a studio setting. I have always been interested in construction and installation, and with several summers of experience working with my hands, I knew I had at least the basic tools to be successful in the course. Through the semester, students in the studio course were given tutorials in how to use the equipment in the wood and metal shops and practicing techniques such as casting and carving. The course emphasized collaboration, and for several projects I was paired up with other students in the course to challenge my own creative process, and work in tandem with other innovative visions to make meaningful, substantial works of art. I came away from the course having fabricated some of my most proud creations to date — I even surprised myself quite a bit with what I was able to make.

But this brief introduction into sculpture was a turning point for me, where the concept of each piece became the focal point of the work, not always its aesthetic value. I was amazed at my ability to work with found and recycled objects, transforming them into new forms and unconventional scenes. But all of this was only possible because I had the opportunity to manipulate these materials in the shop. Take for example my piece “Videodrome 2”

Using a salvaged tube television and a wax cast of my own hand, I had to construct an internal structure for the television to support the rearranged components and provide a new physical skeleton for the TV. I had to carefully measure and cut pieces of wood, then cut and weld a hollow aluminum tube to support the hand and the aluminum vortex component behind the shattered screen.

What began with a simple concept – to replicate and make physically present one of the most jarring and shocking images from the 1983 Sci-Fi/horror film “Videodrome” of the hand reaching through the TV – became a new static exploration of the relationship between humans and technology. However, my concept in this form could only be realized using the tools available to me through the sculpture course and the resources available at my school.

But what happens to an artist, or even a course focused on art-making and art-creation when these conventional tools are no longer available? This is the focus of the course “Sculpture in Expanded Fields” offered at Bard College Berlin this semester, led by David Levine.

Bard College Berlin does not have any sort of workshop for students to work on physical constructions for their sculptures, nor any physical media for students to work with. Instead, the students have full access to the audio-visual equipment belonging to the school, with a number of projectors, mixers, microphones, recorders and speakers available. Quite a few of the assignments in the course have prompted students to explore installation using sound, light, video, and the completely malleable and transformable space of the Bard Berlin Factory.

As I am not a member of the class myself, I asked for some insight into the projects and processes employed in the class by students who are working in the studio. First, I heard from Nadia, a third year at Bard College Berlin, about the arc of her work in the class this semester:

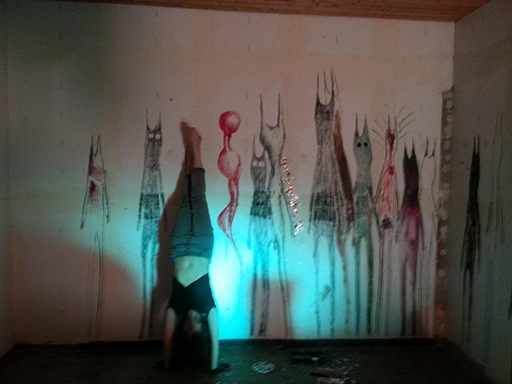

“Weirdly, my studio became a project on it’s own; after covering the walls with drawings of imaginary creatures and maps of non-existing cities, I started inviting people over to talk and to work together. Once I had few people over, and they ended up coloring the creatures and adding to the landscape on the walls, which for me was an exciting and somewhat scary experience: the initial drawings were very personal to me, but seeing how what used to be only in my head was being reinterpreted by my friends was priceless. I like thinking that this room now is a place of inspiration for more than one person; and it looks like the process of making an artwork is turning into a collaborative artwork itself.”

Students in the course were each allotted their own room in the Factory to transform, beautify or ‘destroy’ as they saw fit. For Nadia, the central aspect of her work through the semester became the transformation of her space to turn it into a room for creation, collaboration and socialization. What at first didn’t seem possible to Nadia, for the room itself to transform into an artwork created by her and the rest of her class, became a reality, and an expanded project that lasted through the semester.

I also heard from Sam, a third year student visiting from the Kansas City Art Institute. He says:

“It’s kind of hard to talk about this class specifically without giving some context to my studio practice, so I guess to be brief: I am interested in the stories of spaces. This semester I have been borrowing the idea of a mental space, and exploring the role of different materials and narrative forms. Which is to say, I am interested in how space is represented. I am interested in narratives, and how representation and physical construction converge in a technical narrative – a narrative driven by empathy with the construction of the thing. I want to make work with formal content, whether the subject is formal or conceptual.”

Like Nadia, Sam was also interested in space, but in a slightly different way. He shared with me one of the video projects he made for the class, exploring light and darkness, space, sound and silence. His video project “My Fears and My Hopes” traces a light in two dark rooms, slowly illuminating each detail, moving across the floor. He controls the viewer’s access to his space, only letting us see small fractions of the room in any given second, if we are to see anything at all. You can watch it here (turn the volume up!).

With such limitations for the artist taking part in the course, analyzing and discussing the success of each piece is essential for the artists and other classmates to critically assess each decision they have made and look at the successes and shortcomings of each work. I asked another member of the class, Bard third-year Kellan Rohde, about the critique experience in the course:

“I’ve been in several studio arts classes with crits before, and David Levine’s is one of the first that consistently gives agency to the artist. We, as the artists, are allowed to talk about our intention, our material, our goals. You often hear “Did (x) work? What’d you think of (y)?”. Some instructors like to organize crits based on a “gagged artist” rule, where the artist is the only person not allowed to speak.

The crits are interesting because of how easily it flows into a conversation from comments. The chemistry of the class is such that we can find ourselves sometimes on a totally different subject that is rooted in something the artist conveyed in their work. Sometimes we all agree, silently, that the piece invites no more contemplation than given already. Crits are about teasing out the kinks and errors of your visual language. It is a grammar lesson and speech therapy for the visual.”

While “Sculpture in Expanded Fields” does not have the same resources, nor provides for instruction in typical sculpture techniques — such as casting, carving, or tutorials in the shop — the course is actually working towards a goal somewhat bigger than a typical sculpture course. Through the emphasis on concept development and execution, and the critiquing process, students have the freedom to make more with less, and to challenge themselves to make solid ideas for their art rather than solid fabrications. Additionally, the methods and equipment available to students in the course will certainly benefit their future artistic endeavors, helping students to develop more skills, and more familiarity with light and sound technology.

It’s not uncommon to stop by the Factory at night to see students in the course labor over each minute decision they are making for their pieces, or hear talk about concepts for the installations over lunch in the cafeteria. With the freedom to make whatever they want (and possibly can), the students in this course are engaging with their own creative processes, and challenging themselves to make the most substantial work possible.