On April 16th Irit Dekel, instructor of the Past in the Present: Collective Memory, Politics and Culture class, led a trip to the Anti-Kriegs-Museum (Anti-War Museum) in Berlin. Opened by Ernst Friedrich in the 1920s in the working class district of Wedding, the museum was closed for many years before it was re-opened by Friedrich’s grandson, Tommy Spree, in 1982. Mr. Spree kindly agreed to give us a personal tour of the Anti-War Museum to talk about both its historical and present-day activities.

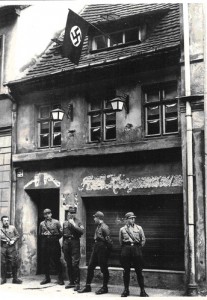

The Anti-War Museum is a contested space, and nowhere is this more evident than through the history of the building itself. It was taken over and destroyed by the Sturmabteilung (or SA, the Nazi storm troopers) in March 1933, and although Ernst Friedrich managed to move most of his archive to Belgium and establish another Anti-War Museum, the original museum on 29 Parochial Street was turned into a notorious torture chamber for the SA, and later for the Gestapo.

Although I can only speculate, I imagine Ernst Friedrich was a witty man. He was a renowned author of political pamphlets, and the fact that such an internationalist and erudite man opened an Anti-War Museum on Parochial Street is not without irony. And along with his courage, most clearly evident in joining the French resistance (although he was a pacifist and would not fight, he wanted to oppose fascism), he must have also possessed great élan, since he allowed soldiers to enter his museum for free, and announced this on the front window – a practice Tommy Spree continues to this day.

As Freud has noted, a great deal of active energy is invested into the act of being passive, and this was evident in the pacifism espoused by the Anti-War Museum in several ways. Mr. Spree opened our session by asking each of the participants as they walked in whether they were a pacifist, and ‘if not, why not?’ (a confrontational method, but one I appreciated.) He also wore a distinctive symbol on his jacket lapel, one which hung also outside the museum: a rifle being broken in two. As our seminar leader Irit Dekel asked: how much violence would be needed to actually break a rifle, or indeed all rifles? This active passivity has been with the museum since the beginning, if the title of Ernst Friedrich’s first book is anything to judge by – War Against War (1924).

The tour began with a short video outlining the history of the Anti-War Museum. Tommy Spree quickly found his groove (well-oiled after many such tours, I would venture) and spoke about his grandfather’s pacifist efforts and the current goals of the museum. He then led us through two small rooms packed with curious objects, like photographs of Hiroshima victims, old guns and passports, and down into the old cellar which had been ‘appointed,’ in a style known to all children of 1940s Berlin: as a bomb shelter. We spent the last twenty minutes of the tour speaking about what it was like for those children and parents who had to spend night after night below ground, before being led upstairs and back into the daylight.

During his presentation, Tommy Spree would often present statistics, say about the number of civilian deaths in WWII or the vast resources poured into arms development, and then question why war must be seen as a necessity for these vested interests. During his forceful advocacy for pacifism, the question most pressing in my mind was: since history has never really known the absence of war, what makes our time so exceptional that we can think pacifism is viable? I decided not to ask Tommy Spree my question, not only because I suspect there is no final answer but also because I believe that the impossibility of our desires is no argument against our desiring them. A pragmatist who thinks war is inevitable has no answer for an idealist who advocates pacifism, since desire finds no justifying ground in calculated or pragmatic goals. However, Mr. Spree did provide the examples of Panama and Costa Rica as an alternative to other war-mongering nation-states, since, according to him, these two states decided they no longer needed a standing army because they were surrounded by friends and so had no need for defenses.

Tommy Spree also spoke about the soldiers who would visit the museum, and I wondered what their reactions would be. Would they propose a version of just war theory, in which apologists of the empire argue that the peace created by a powerful army (such as the Pax Romana) is worth the loss of lives for achieving this peace? Coming from a former British colony, I have great skepticism towards this attitude: no doubt, to those in a castle an open field looks safer when it is surrounded by a fence, but to everybody else it simply looks like an expression of might. But whether this might can truly be opposed by pacifism is still an open question—for me at least.

I think that more widespread support could be found for the arguments presented by Mr. Spree against the use of the atom bomb and chemicals like Agent Orange in Vietnam[i]. He argued that technological warfare on a mass scale is truly inhumane, and I agree with him. At this point of the tour, I could not help but think of the little-known Australian journalist Wilfred Burchett who courageously escaped the American curfew in Tokyo to report on the effects of the bomb in Hiroshima. When he arrived in Hiroshima he sat down in the rubble, perched his typewriter on his knee, and wrote as headline:

I WRITE THIS AS A WARNING TO THE WORLD. The atom bomb is, indeed, a warning to the world: a warning that technology has so far outstripped our capacity to manage it, that we are all in danger of a nuclear holocaust. When Wilfred Burchett arrived back in Tokyo (that very same day he had visited Hiroshima), he criticized the American staff colonels for denying that there would be any lasting effect from the radiation of the atom bomb, and cited as evidence his recent trip to hospitals in Hiroshima filled with people severely ill from radiation poisoning.

The Anti-War Museum is an interesting place and a laudable achievement. Personally, I found the objects—many of them originals—the most interesting: old posters, photographs, helmets, guns and passports. The most memorable was a baby’s crib sealed with plastic to protect against gas attacks and fashioned like a carry – all so that a mother could walk around the street with it (and complete with a little pump for air!). But as much as I respect Tommy Spree’s achievement, I found the appropriation of the truly diverse figures for pacifism in one of the rooms reductive and suspect: Gandhi’s form of pacifism is notably different from Jesus’, and Kant and Lao-Tzu were both in the room, though I’m still not sure in what way either was a pacifist. And while here I may be revealing my theoretical bias, I do wonder how one can justify pacifism without reference to a transcendent good – if one were to look at life as it is lived, without reference to any category beyond it, violence and conflict seem as inherent to it as joy and consideration. What I admire about figures such as Ernst Friedrich and Tommy Spree, however aware of life’s violence they may or may not be, is that they can distinctly and courageously recognize that, when this violence turns into war, humanity as such is invariably the loser. However diverse and complicated a social phenomena war may be, it always shares several traits: the working class fights the war and dies in it, immeasurably more civilians die than combatants, and many companies profit from the misery of others. For this reason, as well as the novelty of the very idea of an Anti-War Museum, the place is worth a visit.

[i] As a side comment, chemical warfare is not relegated to the distant past: recent studies have shown that many children have been malformed by depleted uranium in shell casings left over from the Iraq War. For further information please see this article in the guardian- http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/may/26/iraqis-cant-turn-backs-on-deadly-legacy