You may say that The Danish Girl is an “Oscar movie”, a film whose making was not primarily motivated by the authentic artistic expression but money-grabbing. You wouldn’t be entirely wrong but you’d be largely inaccurate. This film is not a spoiled child of the Hollywood industry. It is not a grown-up either. It flourishes in the power of adolescence. Almost completely self-sufficient and original while still heavily reliant on our forgiveness and sympathy for its idealism and naivité.

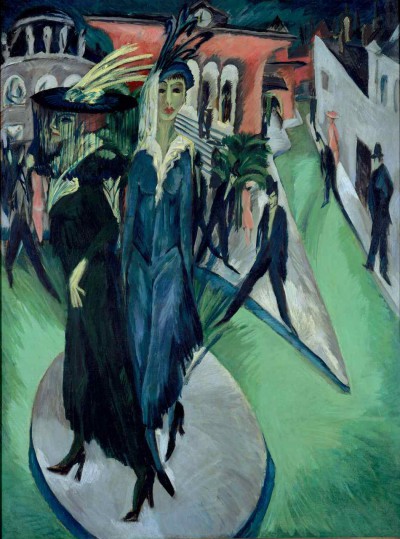

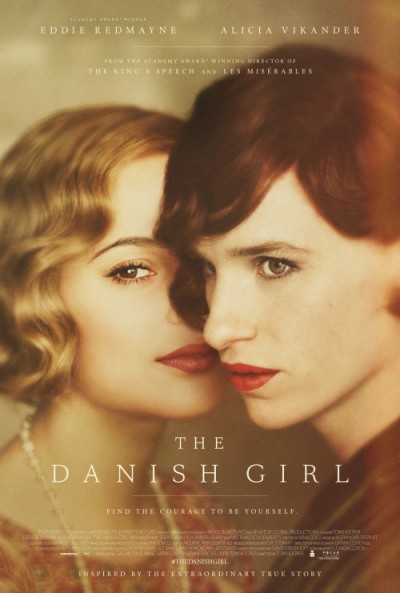

It was a Saturday night when I first saw The Danish Girl. After a long day on campus the M1 was crowded by the German public. There was an unusual surplus of little kids and dogs on board which kept me wondering if there’s any kind of demographic correlation between the number of dogs and the number of children. Maybe kids don’t cry so much when there’s a fun-loving doggy at the house. Such are the simple thoughts I have when life feels easy. Glaring at the flashing stream of light of the city, images of the trailer rushed to my mind. Two faces, two girls as if friends from a forgotten era, like those on Kirchner’s Potsdamer Platz in the Nationalgalerie. One looks shyly past the viewer like Scarlett in Gone with the Wind; one confronts the viewer like Bert Tarleton in the same movie. The Danish Girl. The title like a sticker on two Mr. Tom bars glued them together like two sides of the same person. Or maybe there was only one… Here we were. Hackescher Markt. Before the screening I was talking with my girlfriend outside about typecasting and how it influences the way we value a performance. Maybe I had my preconceptions about this film in mind as I was getting more and more scared that it would strike me as another attempt to climb the Oscar mountain. Our friend arrived and we climbed up the beautiful staircase of Hackesche Höfe. The lights went out and the movie… sorry… a peculiarly sexualized german Ice Tea commercial began. Then the film finally started.

My fear was gone. What a glorious and simplistic way of starting a movie! Romantic images of the Danish landscape: fields, rivers, grass, cliffs, and the sea. A painting engraving this fleeting impression into the canvas. Then suddenly, a girl looking at this painting. There we have it. The hook. Introduction to such a wide variety of themes and the supporting character, Gerda.

I will cease to mention all the shots that followed to save the reader from listening to redundancy. As the movie progressed with a somewhat forced display of a marriage between two Danish painters, Gerda and Einar, we came to realize the inner conflict of the main character, ingeniously played by Eddie Redmayne. There is one particular scene I’d like to mention here. Since the couple’s friend, Ulla doesn’t make it to the sitting, Einar has to model for Gerda’s painting. First he refuses to wear women’s clothes but later we witness the first traces of satisfaction he feels while sensually touching the fabric. Every touch and every look is intensified through Danny Cohen’s beautifully expressive cinematography in this silent study of character. Later on we see that Einar’s embracement of Lili (his true identity) is not only displayed through often melodramatic and obvious ways but through the playfulness of a genuine encounter filled with excitement and experimentation. Gerda encourages Einar to dress up as a girl, after he’s caught wearing his wife’s silk negligee. We follow them sneaking into a theater storage trying on different wigs and costumes like two kids just casually playing around. Then they go to a party where the unimaginable happens. Einar, now completely surrendering himself to Lili, kisses the flirtatious Henrik, an act which is unbeknownst to Einar witnessed by his wife. This initial love triangle triggers the conflict between Gerda and Einar/Lili.

At this point I can’t help but mention the audience’s response to these scenes of self-realization. I was often annoyed by the laughs from the crowd who were clearly thinking that this film is some kind of semi-comedy in which this protagonist is confused about his sexual identity and dresses up like a woman out of mere confusion and silliness. Very much like the society that condemned Einar at the end of the 19th century and offered diagnoses of ’chemical imbalance’, ’sexual immorality’ or ’schizophrenia’. This disappointing experience made the film all the more intriguing for me as I started looking at it not only as a documentation of history but rather a universal critique of bigotry and, more importantly, what we perceive as normal. And what a mindful prank this film pulls on the audiences not well prepared for the coming seriousness and psychological depth as the film progresses from often (perhaps intentionally) boring clichés to intricate clues to how and at what price this protagonist brings her own transformation to life. We should keep in mind (and believe me, the film makes us keep in mind) that transgender roles were considered abnormal and a form of insanity until very recently. Even the scientific world agreed, almost without dispute, and would have wanted to put these patients into mental hospitals and apply fatal „therapeutic” methods to them.

The social context is indeed important and kept me wondering for a long time if ’insanity’ itself is a social construct and what we call “insane” might just be a way to label people that are not coping with our norms so we can isolate them and keep them away from our so-called values. But let’s not forget that this is just the subcontext. Although this is a pioneering effort to deal with transgender issues on the “silver-screen”, the story itself is all about love. Gerda is making an immense sacrifice during the movie and what for? Well, she could easily think that her husband had just gone insane since her whole society is reaffirming this notion but she miraculously doesn’t. She believes that Lili is real. Seeing Einar’s suffering she is willing to lose her husband to commit to this belief. „Einar is dead. We both have to accept that.” says Lili. How would you respond to that as a loving wife in the early 20th? That is the very tough question that the movie asks us throughout. It shows unimaginable courage to stand alone by your partner in order to help them kill the part that you love and believe that this person that you’ve known and loved is a disguise. You could say that The Danish Girl is full of melodrama and clichés but maybe you would mistake melodrama for deep emotion and clichés for a build-up to a meaningful study of love. Gerda is not perfect. She has trouble supporting Lili as an individual until the very end. She says about her marriage: “I know it was me and Einar. But really it was you and me.” Lili is not perfect either. On the one hand she eases Gerda’s pain as she helps her understand and keeps loving her (she kisses her on the lips on the way to the first operation), on the other she often seems egocentric and ignorant of Gerda’s feelings (she kisses Henrik and flirts with Hans in front of Gerda). Maybe there’s some truth in Gerda’s warning: „It’s not all about you.” In conclusion these are far from being clear-cut, one dimensional characters and their lines are far from being clichés.

Alicia Vikander and Eddie Redmayne must have had a hard job breathing life into the often mechanical script but they did. I haven’t seen a film this year that was so dependent on individual performances. This film could have easily turned into a disaster but the two actors keep it lively and real. Their interaction is by far the most enjoyable thing that happens on the screen and it is a pleasure to watch as they prove that acting is indeed essential to a certain kind of filmmaking. Redmayne plays Lili with such humility and love that he makes her character more believable than that of Einar, which is monumentally important in securing empathy for his transformation in the viewer . Alicia Vikander had almost nothing to work with to form a genuinely interesting character but she gives such rhythm and unexpected liveliness to Redmayne’s performance that it is a to watch. Every single reaction of hers, every single line gains such meaning when you see these two actors continue to propel each other to greater heights . It is an incredible insight into acting.

The Danish Girl is a film that you don’t have to watch twice but you should definitely see once in your lifetime. Its social commentary gives it historical significance and its love story depth and liveliness. It’s a fun movie to converse about after a Plato or Nietzsche class or on the way to Rewe. Please go and see this film so you can have long, passionate arguments with friends who thought it was dumb and shallow and friends who thought it was rich and genius.

Thank you for your words, which are perfectly in tune with my feelings.