I only ever knew Clare Wigfall’s work on paper, so seeing my former creative writing professor read a story, microphone in hand, lit up in the far corner of the lowered stage, I was struck by the realization that creating a story could exist outside of just writing one.

“What makes a story?” I thought, as I sat watching The Game is Not Over, an immersive dance and visual performance that managed to unfold the non-linear narrative written by writer and former student of Clare Wigfall, Sharon Paz. Though I’ve always known stories can take many shapes, folded neatly into the confines of a notebook or spray painted onto the walls of Berlin, I’ve always wondered how to portray them in a way that requires and engages an audience. In a way that simulates an experience outside the context of simply watching and observing action unfold before you.

There seemed to be multiple storylines within Sharon’s piece, because of the abandonment of linear time within the construction of her story. However, every moment, or fragment followed the same main character (Anne) and took place within the span of just one day. The story began at 1:01 am and Anne couldn’t sleep. We were taken to a description of her dream in which she was underwater and saw the most beautiful water turtle while she held hands with a younger man, feeling safe, so very safe. Next thing we knew it was 5:21 pm and Anne was scrolling through the internet wondering “where can I find a blue sky?” Then it was 2:37 pm and Anne couldn’t stop reading a story she knew wouldn’t help her. With each time jump and fragment we were taken deeper into Anne’s experience and forced to explore her thoughts with her through Clare’s reading.

The performance was located in Wedding, at the performing arts theater on Uferstrasse where the dance school, TanzFabrik is stationed. Walking into the courtyard between buildings to the theater, it almost felt like a ghost town. Peering into the buildings lining the courtyard as I walked by, the windows looked like portals into moments frozen in time. In one of them people moved in unison, following the teacher of a dance class. Another was dark but filled with sprinkles of shifting strobes lights. The courtyard was so quiet, the kind of quiet you only find in places of worship. “Do you know where studio one is?” My friend and I asked a group sitting in a circle outside one of the portals, and it felt like we had shattered the hundred different moments frozen around us with our words. One of them looked up and kindly smiled at us, “Down there,” they said, pointing to a far off door at the end of the long courtyard.

When we got to the theater, Clare was chatting with her friends and colleagues. I was very excited to see her; I hadn’t realized how much I had missed attending her class every Friday afternoon. I was grateful that a handful of other BCB students were present so that we could fill our time chattering about our mutual confusion in finding the theater before the performance started. The room was crowded, a sizable number of people had attended, especially for the size of the performance space, which when we entered looked a lot like an old amphitheater, with the seats elevated at an angle and the stage below.

As the performance began I was struck by the fact that Clare was only the voice actor, not the creator and director of a story, a single puzzle piece in the collaborative experience adapted from Sharon’s original text. She wasn’t a professor or writing coach, like I was used to seeing her, but rather an artist working in collaboration with other creators. Clare was helping perform a story, not write it, so that Sharon’s piece could exist as something people could experience. It can be hard to visualize creative writing transforming into performance, not only because the experience of writing and reading creative works can be very vulnerable, but also because the images it manifests on the page seem almost impossible to replicate on stage. Especially when considering a character’s thought processes, moods, feelings, and reactions, we can struggle to bring these aspects into real life.

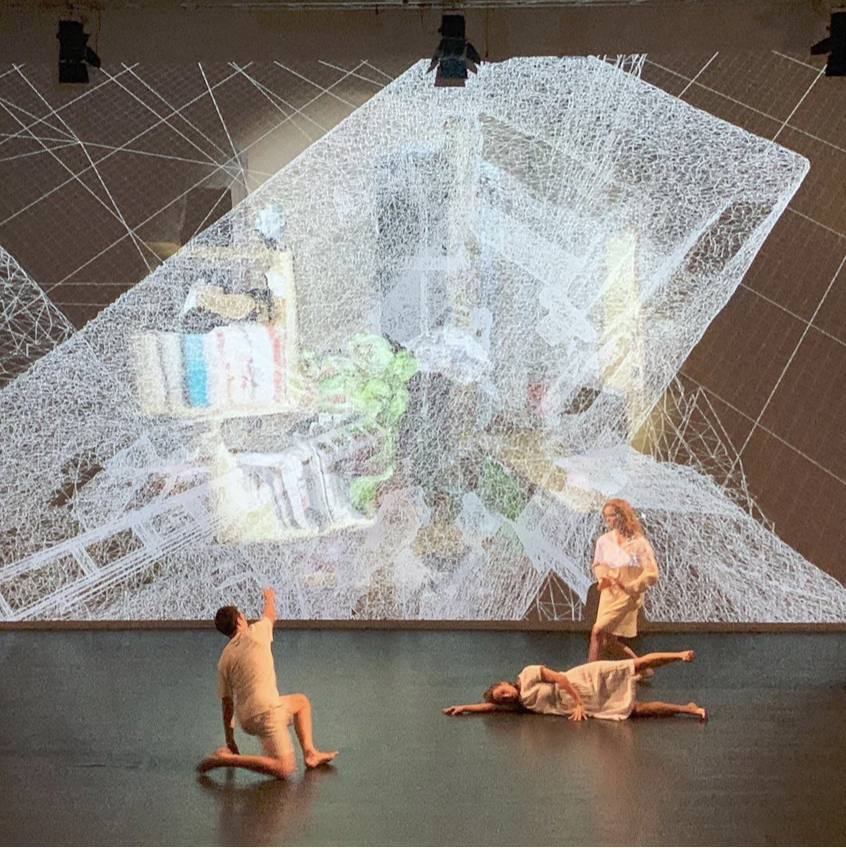

Sharon’s story followed the experience of one woman grappling with trauma and the cyclical nature of an abusive relationship. The performance began with a turtle, projected on the wall before us. The turtle was floating in what seemed like a cramped bedroom, books and towels lining the shelves on the wall, creating a sense of entrapment. Then to our left appeared the projection of a window and the pitter patter sounds of rain. After a few minutes three dancers appeared on stage wearing white and pale blue linen clothes, and introduced movement as the third mode of storytelling. The dancers started slowly, pacing around on stage. Their movements became more tense as the story progressed; sharp abrupt movements illustrated and the main character’s internal struggle with herself. Much of the story was successfully conveyed through the interaction of these dancers, depicting the many forms of communication we may often overlook. In fact, Clare only began to read the story halfway through the performance. The addition of dialogue from the performers revealed the character’s inner struggle, and exposed her thoughts. Clare’s narration provided most solidly the plot of the story while the dance and the dialogue showed the character’s experience. Many mediums merged throughout the performance, with the projector often being used as a spotlight, as it was moved from projecting onto the wall to onto the performers. This created a collage of artistic elements, as fragmented images flickered upon the dancers, both illuminating them and reshaping the originally projected image.

Seeing a literary story adapted to the stage expanded what Clare had taught us about writing in her fiction writing class. Here a story was told not through one person’s creation of sensory details through use of their imagination and their possession of a pen and paper, but by making these details alive and tangible, by bringing them to life. There were five elements which brought Sharon’s story to life on stage: movement, language, visuals, sound, and engagement. These elements were what made the experience, what transformed the reader into a participant in the story. At the very end, the audience was asked to walk onstage. Because our seats were elevated and the stage was below, it felt as if we were walking into a picture, into a world, in which the sounds and sights around us were simulating one singular moment of Sharon’s story. Moving barefoot through the leftovers of what we thought was a completed performance, we hesitantly collected ourselves at the back of the stage, now face to face with the performers who had so unabashedly opened themselves up to us. It was vulnerable, and one could even say uncomfortable, to step out of the safe confines of the observer and into the participant. That’s when, microphone in hand, one of the lead actors began approaching individuals and asking them to share a secret. Unsurprisingly, no one fessed up, yet the process of it brought us face to face with our existence in the performance, no longer able to hide in the shadows of our seats, camouflaged by a sea of heads and shoulders. There was something special about standing there, the lights flickering on our faces, and not before us.

Audience called onto stage towards the end of the performance. Credit – Sylee Gore

After the show, I was lucky enough, with Clare’s help, to talk to Sharon about her process in the creation of The Game Is Not Over. “It was hard seeing my work placed into other artists’ hands and given to a director to choreograph into movement and visuals,” she explained, “but I knew that field was not my speciality, and watching dancers, actors, and technicians adapt it into a new mode of storytelling helped me understand my work better.” I nodded in agreement, recognizing the discomfort and amazement that comes with seeing your work brought to life. I believe it’s sometimes easier to write things down, knowing it’ll never walk off the paper, but that’s exactly what Sharon allowed with her work, which I think is cause for admiration. Then Sharon mentioned another part of the performance which I had not yet discovered; the video game. “You play it,” she said. “You play my story. The game places you in my flat, and by clicking on an object you can uncover more of the story. I wanted to create a non-linear experience of what I had written.”

Objects seemed the perfect way to do that, I thought. Already holding their own value, the reader, the player, could uncover the story using their own perceptions and gravitational pull towards certain objects. Here was the simple conversion of the reader into a player. A recognized contributor to the story, just like the process of bringing the audience to the stage. And Sharon had used a variety of objects to do so, from a pair of red high heels to a computer, a dustpan and garbage bag. How much of a story is really told by the creator of it? It seems that it is the imagination of the one interacting and experiencing the story that actually puts the pieces together, making sense of a narrative no matter the mode through which it is told.

So what makes a story, and how do we tell them? Clare had taught me that stories are told everywhere, sprung out of the explanations and assumptions we attach to any and everything. It seemed that this performance was a demonstration of that which she had taught, showing the many ways in which stories are made and understood. It was inspiring to see the professor who guided my own writing explore different modes of storytelling herself, especially when being a part of someone else’s work outside of an academic institution. But most of all, seeing a story come to life through merging different ways of expression allowed me to reimagine ways in which I can tell stories. It is encouraging to witness creativity outside of the classroom, for sometimes we have to see the possibilities of it in order to understand the many forms it can take. For this performance could not be contained into a definition of spoken word, dance, acting, or visual performance, but a combination of all. It was as if my childhood dream of living in an imaginary world was made real for one hour, helping me understand that perhaps the worlds we imagine, the moments we relive, can be made into an experience for others. Sometimes writing can feel contained into an experience only witnessed within your imagination, only able to be shared through passing the paper to another, or reading it aloud. I’ve always wanted to discover a way to perform stories outside of the usual way of adapting them into a play or other traditional modes of theatrical performance. Sharon’s performance allowed me to see the abundance of shapes a story can take, and encouraged me to explore different ways of creating through witnessing a writing mentor do so herself. Watching my former professor not only bridged the invisible gap between teacher and student, but helped me recognize that being a creator is something that is always shifting and growing, and never stagnant. That those who love what they do will keep at it, that I can keep at it, that you can keep at it. Art is not limited by time and space, squished into our academic calendars, but flows naturally from our participation and curiosity at the world.

Clare Wigfall with the microphone. Credit – Sharon Paz