It is likely that the words “Liberal Arts Education Panel” have been swimming through your subconscious as of late. These words were printed onto pretty paper flyers placed around campus within your easy view; they made the difficult but certain journey through cyberspace – presumably from the P98a admin building, in the form of magical stardust – all the way to your inbox. They have now come to rest at the forefront of your mind, treading the unknowable waters of your conscious, where they run the risk of being carried by different streams of thought to the back of your mind unless you hold on tight and follow me in this unexpected and unprecedented Liberal Arts journey.

If you are anything like me and most other people, you’ve got just about a gajillion different things on your mind all at once. I’ll admit that when my eyes first glossed over the minimalistic poster on the cafeteria bulletin board announcing that a Liberal Arts Education Panel discussion was to take place in the evening of February 12th, my curiosity was piqued only momentarily: As the lunch line shuffled slowly forwards, my brain chewed the words quickly, swallowed, then filed them away in an indeterminate location to be digested properly at a later date.

Even as my feet found themselves walking the now familiar path to the Lecture Hall on the fateful and advertised evening of February 12th for the planned panel discussion, I had no idea what I was getting myself into. Even afterwards, as I paced back to my apartment through the biting night air, my head excitedly churning half-chewed thoughts, and even as I write this, I have no idea how to define exactly – if at all – just what it is I have gotten myself into.

It seems that no one in the Liberal Arts Education business really does. Though this ambiguity may seem the greatest and defining weakness of the Liberal Arts to those not engaged with it, further examination and inquiry reveals that this ambiguity is, paradoxically, its greatest and defining strength.

You with me so far? This whole thing will require some charitable suspension of your disbelief.

The Liberal Arts panel discussion held by Michael Weinman, Geoff Lehman, David Hayes, Ewa Atanassow, and David Kretz this February was a continuation of and elaboration on a presentation they held at the Liberal Arts & Sciences Education Conference at Amsterdam University College in September 2015. Moreover, this panel discussion was a continuation of and elaboration on pretty much all the questions that a Liberal Arts Education has been concerned with since its inception a few thousand years ago, dating all the way back to Socrates’ time – but we’ll get to that later. The focal question of the evening was “Why and how shall we read Core texts today?”. You might have asked yourself the same thing when you were presumably pondering Plato’s Republic in your first semester at BCB. (Or maybe not. Or maybe rhetorically, frustratedly, as I did)

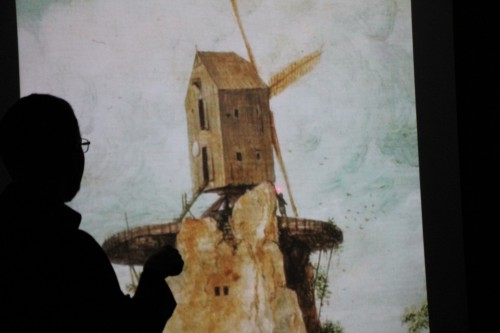

The evening was divided into three presentations that at first seemed distinct to me, but that I now realize informed one another beautifully. Geoff Lehman gave the first presentation, in which he addressed the question of how a work of art can be thought of and engaged with as a text in a Core course through what one could call the “critical analysis” of Pieter Bruegel’s painting Via Crucis as might occur in a seminar-based class.

As became clear over the course of the evening, the type of critical analysis up for discussion here is not the problem-solving type you usually hear about as being fundamental to the Liberal Arts. We’re not talking about critical analysis as it is commonly conceived. The rich, subtle, intricate, and sensitive interpretation that Geoff presented of the painting was “a mediation between reflective detachment and emotional engagement”. It is this type of analysis that, Geoff proposes, is at the heart of a Liberal Arts education. It is not an ability that will be magically instilled within anyone who chooses to pursue the degree program. The Liberal Arts demand that we practice this mediation from the get-go in order for our education to succeed – for us to succeed in education. In exchange, it enables a richer understanding of the world and our status in it. Plus, we get an ambiguous label slapped onto our diploma for practical/worldly reasons.

This approach is contrary to the ordinary conception of critical analysis in that it does not presuppose a text is like a puzzle to solve: “Its irreducibility to our understanding is part of its fascination,” concluded Geoff. He addressed both the “how” and “why” of the question of reading Core texts today by demonstrating that to attempt to whittle the painting down to the interplay of color on canvas would be unfair both to its nature as an organic whole and to our own understanding of it, as it would be to any Core text.

David Hayes picked up on this same line of thought with a speech on “thinking towards belief”, wherein he criticized the ordinary conception of critical thinking as something that, if put into practice, makes one’s belief “thinner” and buffers our understanding of any particular text. He observes that the common practice of critical thinking presupposes that belief is easy, and that it is our responsibility to rid ourselves of our false ones. But to view texts, the world, or the opinions of others with such suspicion prevents us from seeing the value that these things could add to our own lives and how they might enrich our own beliefs. In the discussion following all three presentations, there were multiple questions directed to David on this subject. Nathan French, a second year BA student, voiced a reasonable objection on value: “If we don’t question our beliefs, how do we know that they are of any value?” David’s response to this was that “the test of whether something is worthy [of our belief] isn’t if it doesn’t scream under torture”. He proposes that we read Core texts charitably, with the willingness to suspend some of our own beliefs and entertain others’; without the (limiting) belief that we are there to rid ourselves of ours, or that we could somehow possibly be wrong in our impression of any particular Core text. We must value each other’s opinions democratically and “strive to inhabit the viewpoint of another”. We must earn our beliefs. This “requires charity”.

It seems to me that David is further outlining a type of bravery; you must put yourself at the mercy of valid uncertainty and ambiguity. It is through this dual bravery and charity that we are able to “thicken” our belief – not just in a classroom, as David pointed out, but in all spheres of life.

But what’s the use in theorizing about it? Zsofia Hornyai, a 3rd year BA student, brought up a point during the panel discussion that I think gets to the heart of this whole Liberal Arts education/critical thinking business and its relevance to us students: “It seems like we’re arguing in favor of something that’s unavoidable. We’re going to come out of this education with some sort of belief. It’s kind of impossible not to.” I see where Zsofi is coming from on this one. While taking notes during the lecture, I jotted down objections of my own to the seeming abstractness and possible irrelevance of the conversation to our everyday classroom experience. We all know those days when seminar conversation is insipid, or when one person stubbornly refuses to “charitably” entertain any notion other than their own. David conceded in his speech that his approach, which attempts to disassociate itself from this worrisome critical thinking business, is an ideal. But this – its seeming unworldliness – is what makes it relevant and worthy of careful critical consideration. Instead of disregarding his pedagogy off-hand as ultimately unachievable, we ought to charitably entertain it as a useful utopia to strive towards. Yes, we are going to come away from our education believing something, and, yes, it’s kind of impossible not to. But we have to ask ourselves if we want that “something” to be the same something that we believed in when we started the BA programme, or if we’re going to be open to the certain possibility that our peers have much of value to contribute to a given discussion and, moreover, to our own beliefs.

This is not easy. It is something that we must constantly remind ourselves of. I’ll admit that after I finished reading the first book of the Republic last semester I was utterly unamused. The interlocutors seemed only to be mincing words. This whole philosophy thing that I had been looking forward to was so simplistic. At first, I listened to the Core lectures and seminars with skepticism. Then the skepticism fell away. Philosophy became … exciting! I now understand why we read what could be considered frustrating and unyielding texts: They are not to be attacked. To re-iterate Geoff’s insight, the “irreducibility [of the texts] to our understanding is part of [their] fascination”. We can’t expect our first (or second, or third…) glance at any given text to imbue us with understanding. We must bravely think towards belief. This is true not just of paintings, Plato, or the poster you might also have skimmed while standing in the lunch line, but of pretty much 100% of everything, ever.

Michael Weinman artfully explores this subject in his own response to the panel discussion, “Perspectivism without Relativism”. (Aside from indulging in its delectable aesthetic, I’d highly recommend reading his article so that you might also get a better impression of how finely this web of conversation on the Liberal Arts has been woven). I would like to call attention to his commentary on the relationship between the individual student, a Core text, and a pluralistic society. He continues the conversation with many before him: In a world that is “centerless and infinitely divisible and infinite in extension, […] shot through with inherent plurality and hence difference” and filled with individuals that have a “single experience” of it, Core texts (themselves created by singular beings in this inherently pluralistic world) are able to “yield an interpretive openness in seminar participants that differs radically from the ‘critical’ attitude taken so often to be the basis of a defense of liberal arts education.” To use less beautiful words and substitute the terminology introduced in the panel discussion, a Core text provides a platform on which we, when engaged with (charitable) seminar discussion, may strive to think towards belief.

But there are those who contest the current structure of our curriculum, and who have called for a re-evaluation of its content in adequately meeting what Ewa Atanassow outlined for us as the “Aristophanic challenge” of value pluralism in a democracy. If we were to put this challenge into a question that acknowledges its relevance to our own studies and beliefs, we might ask ourselves “Why and how shall we read Core texts today?” This question has recently taken the form of a debate on diversifying our curriculum at BCB.

Aristophanes’ The Clouds – itself a Core text that neatly demonstrates the relevance these texts have to our lives – is a comic Greek play written by the famous playwright Aristophanes in the 5th century BC. It is the oldest attack on Socrates and the Socratic method. Without getting into the details of plot and character, the main accusation that Aristophanes levies against Socrates is that his form of education is, to quote David and Ewa, “useless at best and possibly harmful for a democracy because, in its unworldliness, it is unable to orient a student’s soul to civic mindedness and the common good”. As David outlined in his presentation, the problem we face in structuring the curriculum is how to mediate between dogmatic indoctrination (that purports one truth) and accepting relativism (that everyone is ‘sort of’ right).

David expressed in his joint presentation with Ewa that “the curriculum has come under attack as not addressing sufficiently the diversity of values and voices in the student body and contemporary society at large.” David chose to respond to this attack on the Core by outlining the trade off between “historical coherence” and “inclusivity.” He made an excellent case for trying to strike a balance between both that looked to me to favor the former. He evoked the history of the institution of the Core in the form of a B.A. in Values Studies in 2009 and its subsequent evolution to meet student desires while still adequately addressing the Aristophanic challenge. I won’t delve too deeply into the details and history of the debate either as I realized through my own research that it is bottomless (But fascinating! I would direct you to the Public Seminar webpage to which I was also directed if you are interested in exploring it further.).

I would like to draw attention back to the word that Nathan brought up in the discussion that underlies this debate …and our existence: “value.” We can’t escape it. The question “Why and how shall we read Core texts today?” that drove the panel discussion is one of value. The debate on diversifying the curriculum forces us to examine the what, why, and how of value in the Liberal Arts. Both parties in the debate are in agreement that the democratic mindset is integral to this type of education. It manifests itself in Socratic-style seminars and the charitable approach to inquiry that Geoff and David propounded in their presentations. What is being contested is how else this value ought to manifest itself – should the Core texts that we read today be a reflection of the diversity of values within the student body? Or ought they to remain a “minimal and flexible framework” that all students can engage with equally in “thinking towards belief?” I am not overly familiar with the intricacies of the debate, but, as far as I can tell, the question of why we value the democratic mindset doesn’t come up too much. It’s terribly tricky to find a synonym for “why.” To put the question another way: to what end do we value it?

This is a dangerous question because it brings us right back to where we started, wondering just what this whole Liberal Arts education business is all about. (It’s certainly not about the acquisition of a marketable skill for any particular profession, so let’s just drop that for now.) It’s not about impractical ideals or having one’s “head in the clouds,” nor is it simply a tool to be wielded for social and political change. It’s all and none of the above: a blend, a balance – ambiguous.