Light travels on the back of shifting air and this livable box becomes a bag of four winds. My room faces west, which is to say the windows of my room open westward. Really, my room faces all four directions. But the windows determine the front of the room, for it is through them that I can establish orientation at all. The four tall glass panels let in the waves of air and afternoon sun and present to me the day’s decline. And as faithful portals to the greater world, my windows welcome a diverse activation of the senses: breezes perfumed with rain and evergreens, buzzing insects, warm curves of light giving color to my hand drooping out the window and to the congregation of dandelions below. When I’m not nearly falling out of my windows, I’m in the theater box, halfway observing the slices of moon ripen over roofs, skies heaving heavenly glows. The openings are there all the time, visible from any angle in my room. So I can see and feel the whole expanse of outside in a few rectangles even if I’m not looking directly at them, even if my eyes are closed.

A Window is not a Door

What I like about windows is that they open up to something infinite. Unless you’re leaving a building never to return, a door opens up to something closed, contained. You leave a door and look for the next door. And with a door, you close it when you’re done using it. Windows don’t operate in an instant like that, they offer a service of duration. When I open a window, invite the most wonderful and ethereal guests into my dorm room, I don’t know when I’ll close it. If nature allows, I’ll leave it open all the time.

Unlike a door, a window is not a real threshold since it cannot be crossed. It is an impractical space to move through and to travel by window means the door is not an option. A suitor secretly alerts their beloved by throwing pebbles at their bedroom window because they fear the front door. Besides the occasional creative intrusion or escape, the window is an uncrossable bridge between inside and outside; it is not “functional” in this way. We look through them, breath through them, are pulled by the air that comes through them … but do not move through them. The window mediates the space contained by architecture and the expanse of everything around, inviting a confusion between manmade and natural that a door, unless left ajar or made of glass, usually shuts out.

This opening enables the realms of structured human space to bleed into the outdoors. Even the word “outdoor” tells you exactly where you need to go to find the greater spaces, out the door. What the window offers is not a traversable passageway, but a platter of outer impressions. As an optical instrument, the window empowers the eye to lasso clouds into a sketchbook. Without cupping your hand to your ear, the window makes possible the transcription of birdsong onto staff paper. And indeed, the window is the time-honored portal of poets and artists, the wallflower muse. To look out it is to look beyond.

Inside and Outside

Manmade structures of closed interiors are a kind of compressed and solvable maze. We march back and forth through unambiguous compartmentalized zones of function, our movement arising from the specific desire of the moment and devoid of wonder. These spaces are interconnected rooms: closets, nooks, foyers, staircases and hallways that are unchanging. But outside is a space more akin to our true nature: dynamic, in flux, always in the motion of becoming something else. A window is a reminder of this, the reason I twist my head and recognize something big is happening all the time even if it’s just the flight of a butterfly.

Standing outside, especially in the vastness of Icelandic land I return to every summer, I feel a oneness with the environment. My body is continuous with the space as it extends forever in all directions restricted only by the boundaries of my vision. Inside, the space is divided and sectioned off quite totally. Existence in these functional closed-off areas is asynchronous; you’re either in the bedroom or in the kitchen, sleeping or eating. The forgiving divisions of space in a natural landscape of mountains or trees, even buildings in the cityscape, become the impassable ceilings and walls of insides. And certainly, shelter is a most comforting thing. The roof of a house, soft unit of a bed, or warm hollow of a bathtub embraces one into something close and familiar. The expanse of outside can be overwhelming, even startling. To be inside something, closed into a chamber, creates refuge from the enormity of the rest of the world. Windows remind us of the environment’s power without startling us; they keep the message digestible by enclosing it in the architectural language of basic shapes.

Windows are gaps in architecture made transparently solid. Yet they are still of fragile design. More than a wall, ceiling, floor, or door, windows risk breaking. Something feels impossible about windows: their perfect transparency and ability to withstand massive concrete structures as eggshells. Besides the rather startling sound, the dramatic crack and shatter, the sight of a broken window can be unsettling because it makes apparent the thin division between human-structured habitat and something wild. What allows us to watch the world from a safe distance might at any moment meet a hurdling rock and open us up completely.

Openings

But we can also choose to be open. Windows can be opened and left open without the expectation of entry or exit. Visitors of these openings are not solid presences, but arrive rather as nebulous humors of the day. Windows puncture the room, give the building nostrils. Old windows work exceptionally hard to keep you connected to the outside. Even when my windows are closed, cool jets of the night’s pressing air spill into my room and pool on the windowsill. Sometimes I dream of great fields of energy, unseeable forces swirling all around, every room broken and bleeding into each other to inky blackness. Without the warmth of the sun I feel this moving air most acutely. In the morning I hover a hand over the wood and feel the cold emanation, the outside fighting to fill the room and making all the windows glow cold and invisibly. But it’s not the cool air that wakes me, but rather the rising light. It is not my phone alarm, but my windows who stir me into consciousness.

Perhaps the most “practical” function of a window is indeed its admittance of light into a space otherwise closed off from the sky. Since my room faces west, it absorbs the most glorious (albeit sometimes unbearable) sunlight in the afternoon. Too often have I been startled by a dark shape darting across my floor. The heavy shadow of crows flying by enters the inner space through the glass, makes flat, dark, and frightful impressions upon the empty stage. And many a honeybee, bumbler, hornet, and yellowjacket have floated in on warm days when I leave all the windows open. They arrive with great and unmissable gossip, whispering of trees and grass illuminated by light unbent by glass. I’m always tempted.

Distances

There is a wonderful and strange distance that the window allows one to feel. In my second-floor room, this distance is not just in-out but up-down. From a perch, I can look down to the street where the infinity of rotating bicycle wheels can be smushed between thumb and forefinger, hand-holding couples, dogs and their walkers, can all be gathered into a palm. I feel a part of treetops and rooftops. Through the glass, I can realize the oddity of my position, how, if there were no building at all, I’d be floating (or falling). Quite marvelously, I’ve achieved a birds eye-view without braving shaky branches. I’m safe and far up and can be greedy in my looking.

Pleasures of Gazing

A window is a frame for seeing beyond the container of one’s physical and immediate space. It is a peephole that propels the gaze outward. Through it, without really moving, you can confront the same two trees, always there and ever changing, appreciate the paces of birds and bicycles, recognize time in warmth and photons. The window is uniquely suited for daydreaming as it literally displays another place you could be, without requiring the action that would allow for a physical transference, as a door does. Window-gazing, you can become an active absent witness. Observing and participating in the millisecond lives of the passersby, you become something of a flâneur with their feet in cement. In this peripheral participation, you can be half in the world, half within yourself.

Windows activate the mind by possibility and not by certainty. What you see, feel, smell, is filtered by the window, all compressed to fit into the container of the room; it’s never the whole thing. I turn my head to face the glass, seeing and feeling micro-macro events happening in time right alongside me, entities existing simultaneously with my lame position at my desk where I write and ponder small things smally. With my Pankow dorm surrounded by trees, it seems like the whole expanse of nature is squeezing itself into my rectangular window frame, performing something vast and grand, all set behind glass, all beyond my reach. This instrument is a marvelous magic trick of architecture; I can sit still in a modest dorm room within a concrete building and also follow a bird in a tree meters away who is alive in the same moment I am, but probably with more purpose than I can even imagine. Left open, a window accepts the piney fragrance of outstretched branches, the honk of cars, and the saturations of light and sky. It allows the same moving air that animates the front yard flag to grace my face and flutter the white rays of paper in a book I’ve left open.

Visions of Windows

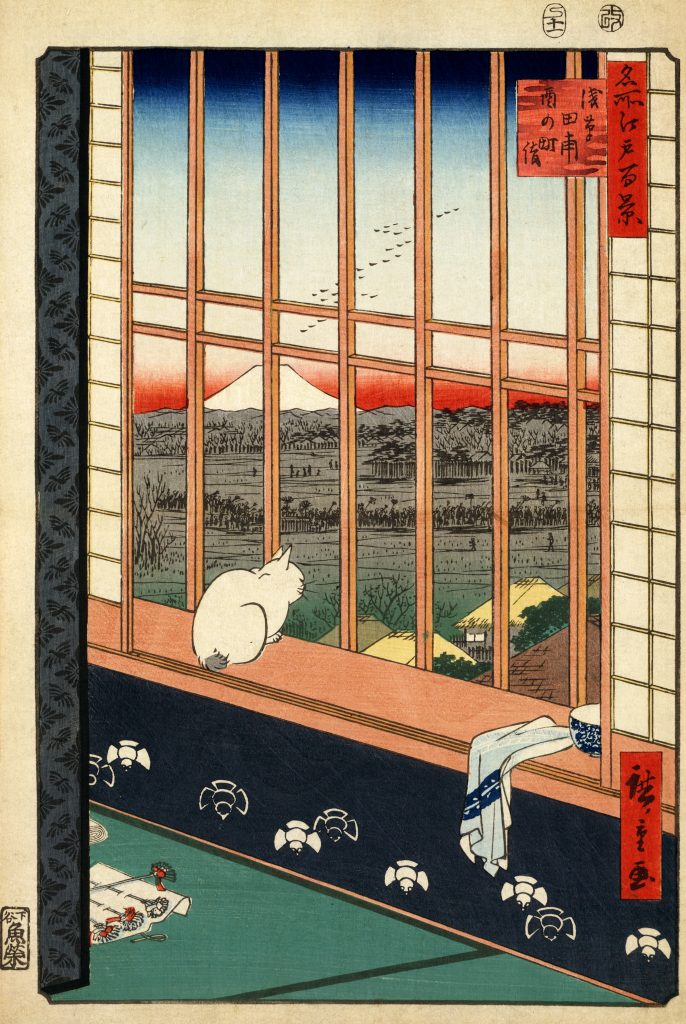

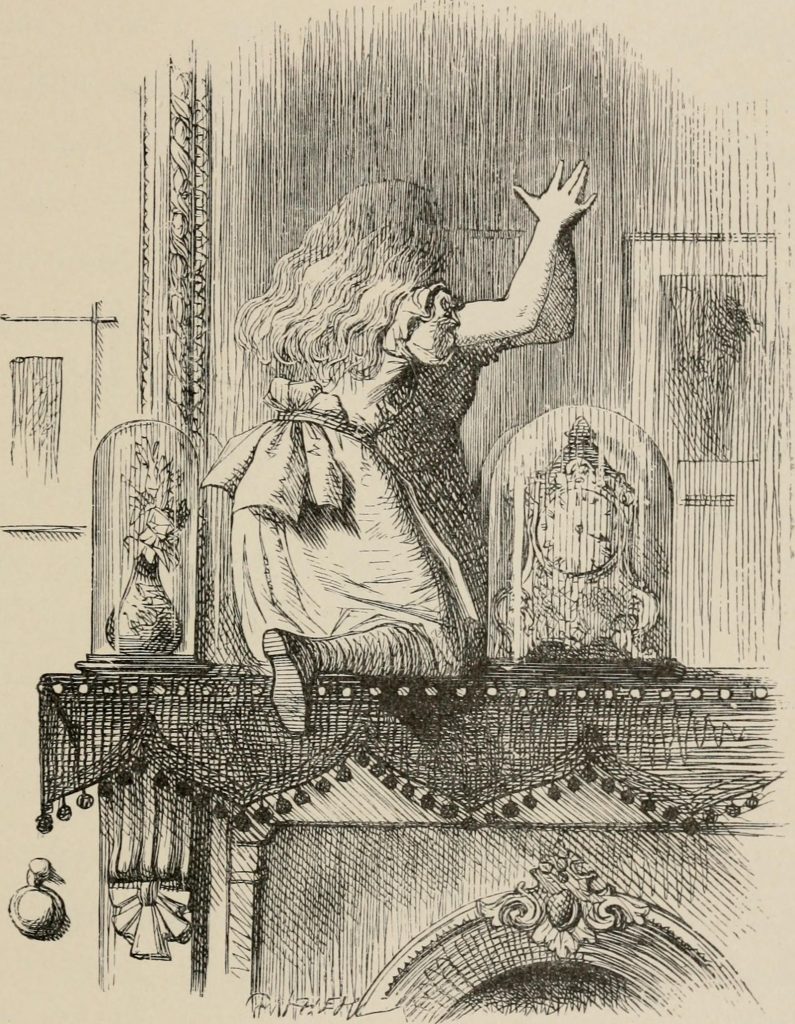

You have to do nothing with the intention of doing something for a very long time before you can actually start that something, is what I thought staring out the window trying to start writing about windows. But what is normally lollygagging is now research. I lean out the window, draw myself staring into space, reread “Prufrock” because I vaguely remembered the mention of a window (line 74), review the illustrations in Alice Through the Looking Glass, and do just about everything except write for a long time even though I thought this would precisely come easily with my being indoors so much. But when I’m not doing anything, I find I don’t have much to write about which maybe makes me a bad writer or perhaps just bored to the point of absurd unproductivity (or both). All my poems these days are sad encapsulations of the last 24 hours. When I go for a walk, the poem is about the walk. When I call a friend, it’s about our conversation. Mostly they’re explorations of my dorm room – plant-lamp-bag-hat – and of course, supreme praises of the windows.

Recently, I dreamt that I stood at an open window in a château (an embrasure) where I observed soldiers marching over a great mountain, an odyssey from which I was excluded. Along the mountain was a giant worm with a human face wiggling ever closer to the château. I was leaning so far out the window that my neck stretched all the way to the ground. The worm with a human face and the sun with a human face looked down on me patiently as I struggled to pull my head back into the building. My hands grabbed lengths of neck as my head bumped against the outer wall. Sometimes my mind was with the work of the hands, and then it would sink to the end of my pendulous cranium. Finally realigning my neck and shoulders, everything in place, I cautiously approached the window once more, terribly curious to see the state of the world.