Afternoon

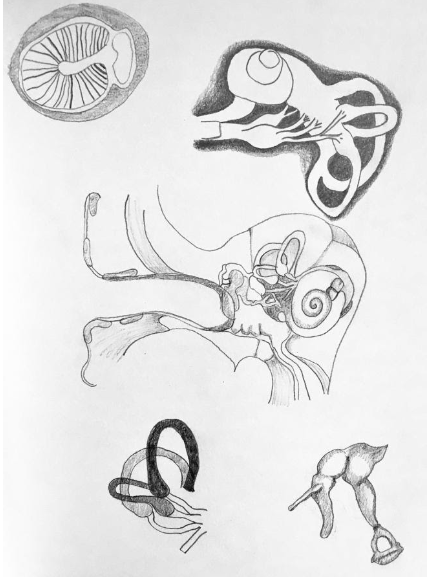

I awake floating over my bed. It’s not often that I find myself this close to the ceiling, this intimate with the spider in the corner, so naturally I’m rather anxious to get my feet on solid ground. The cobwebby tower of books on my bedside table wobbles as I attempt to stabilize myself. My fingers flutter over the thin spine of Macbeth and at last, with a pinky firmly on T.S. Eliot, I push to propel myself to the ground. Arms and legs no longer held by vaporous strings, my body folds and flails as I plop to the tiled floor. I miss my bed altogether. Eyes where my feet should be, I notice my Latin books stacked and smiling next to a half empty bottle of apricot juice by the far leg of my bed. The nightly tilting of the room, imperceptible to the sleepers, allowed the books to slide slowly beneath my bed while I slept and dreamt. I foolishly left these books on the floor. Today’s Latin study therefore begins with an under-the-bed contortion. The notes are hardly legible in that darkness but I manage to read a table of dormio: dormio-dormis-dormit-dormimus-dormitis-dormiunt. Ah! This is a new one. The words march from textbook to lined paper. Crawling out from under the bed, I finally stand, legs shaky and achy from my floating and my fall. I look around the room for the safest place to store the books, deciding finally to place them in the bottom drawer of my wardrobe. By now it is nearly 2:30pm so I swiftly get dressed and grab my poetry notebook and pens. I don’t want to miss the silence of the wall.

Lecce is a walled baroque city in the bootheel of Italy. I’ve decided to stay here alone for three weeks of break before returning to school. My travels and daily ambulation are for the high purpose of reading, writing, and drawing all that is around and within me, which, if I meditate enough, will be nothing. I write to stop writing. I used to think that I possessed a short list of concrete knowings, untouched by wind and sun, all exterior existence. But now I know the knowings change in an instant: I am, quite inexplicably, a different person every time I walk past Basilica di Santa Croce, and I’d love to show you exactly how, evidence of the metamorphosis, but each time I retrieve my phone to take a picture, the device goes pfffffft. Not much to be done at that point.

I arrive at the wall just as the silence is starting! The head-high bushes walk along with me noiselessly. I feel the hollow passages of my ears anew. The wall is immune to my footsteps, my whistling, my breathing. It offers the most divine nothing in the most singular form an Italian wall can, a subtraction and an anti-creation. This stretch along the Mura Urbiche di Lecce is a euphorically peaceful ambulation, a muted funeral march praising aural chastity… The black birds perched on the teeth of the city pay little attention to the flâneur proceeding in slow-mo. It was only yesterday that I lost my right foot to a pencil drawing in my sketchbook. My shoe was filled with air and I had a ridiculous bounce in my step. Now I’ve got the hang of it but I was quite clumsy at first. The birds didn’t care at all. The lazy guardians fall from the wall to sit on the field below. Their wings, so black and deep, create tears in the universe, shifting seconds of void. This is my favorite part of the day, this long block of fortified wall, noble and unintellectual and severe unlike the fainting arches and flowery façades of the city within.

Late Afternoon

By the time I am standing before Porta Napoli, the open door to Lecce, it is 3 o’clock and the city is deserted. The Italian sleeping spell has hit, halting the days and ways of Lecce natives, and I sit in the hollow spaces to write. And I write trite and indulgent poems to the architecture. The Piazza del Duomo bell tower, a cream-colored songbird decorated with nature’s violence and grace. I sing my way to the Roman amphitheater of Piazza Sant’Oronzo where I see the most fantastic performances all by myself. No one else seems to know about the 3:30 tragedies here, everyone sleeps straight through the wails and triumphant speeches and whatever else you find in tragedy. I lean against the crumbling railings, I want to see the eyes within the paper-maché masks. Understanding very little Italian, I imagine the dialogue, stolen from familiar texts. Look like the innocent flower, but be the serpent under’t, says one actor, ‘tis the eye of childhood that fears a painted devil, responds another. Then it’s over. The ethereal players bow and receive roses from all directions, flowers blooming in air and tossed from invisible hands whose form I can only perceive from lithe shadows along the railing. I applaud vigorously, it was really a wonderful show even though I didn’t understand. The ascending-descending seats rise up with the clapping like the basalt columns I know from Iceland. The force of the movement blows flower petals through the decorative openings in the stone railing and for a moment I am in a tornado of fragrant rose, then I join in the flurry. Briefly I am air and I am invisible, although there is no one around to see anything anyway.

Materializing back to my un-flowery form, I examine the piazza for signs of movement. I know the streets will soon be populated once more so I make my way to the café where the same three old men sit and read the newspaper every day. Each morning the barista most tactfully slips today’s paper into the old men’s hands, gently removing yesterday’s news without them ever noticing. He fills their cups with espresso before they’re ever empty and leaves the lights on at night while the three go on flipping through flimsy pages. This way they never stop reading. The most informed men in all the world, right here in Lecce.

I order an espresso at the bar, but, utterly giving myself away, stutter in my un cafe per favore. The barista is of course obligated to put me in the pastry window. I’m already leaning head first into the Cornetti alla Crema before he can steer me to the spot (this isn’t my first time among the pasticcini). From 4 o’clock to 5 o’clock I sit with and count the Pasticciotto Leccese, sometimes including myself in the count if I’m feeling particularly pitiful. The hour goes by quickly, I hum along with the voices of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion coming from the calzones on the shelf above. I always found the music choice a bit odd but enjoyable nonetheless. I try to glimpse the newspaper of one of the old men through the glass, but the steam of his coffee obscures the text completely.

Evening

Off the shelf, back on the streets, I stop into Chiesa di Santa Irene. The interior of this church, like all churches in Lecce, is rather dull compared to its ornate and contorted face. I step over a rope to walk the nave with a rhythmic right-left turn of the head to count the eyes. Along the side-aisles hang images of Jesus, every version with the same concentrated passion. I count eight eyes.

The church is empty at this hour save for three men in grey jumpsuits, one up on a ladder and two below guarding massive tool boxes, occasionally pointing up towards the man above. One of the men on the ground turns to me and says organo? I stand a moment then spin in the nave to gaze at the organ. I look back at the three men who are all staring at me now, six eyes. I shrug. The first man is mumbling something I do not understand as he walks along the side-aisle towards the organ, a huge ring of keys jingling at his hip. I follow, matching his step in parallel unity along the nave. He stops at the spiral steps that lead to the organ, unlocks the little gate, and waves his hand up the stairs. I hesitate a moment and he’s clearly done with me so walks back to his tool boxes, the bells of his keys coloring each step. He returns to his upward pointing.

I climb the stairs and face the instrument. Hmm…I suppose I can sit here and poke a note or two. I place a hand on the first row of keys for a dissonant EEEEHHHH which startles me terribly. I quickly turn to see if I’ve scared the man off his ladder: the workers don’t seem to have even noticed. Suddenly the light of the church changes. The dipping sun shifts shadows along the walls, over the eight eyes of Jesus, draping over the three workers. Not knowing much but with newfound confidence, I play individual notes then try to make chords. It doesn’t matter, the organ’s song brings darkness to the city. When I leave the church, it is night.

Night

At 8 o’clock I grab something to eat from a bakery and head to my dinner spot: the protruding edge of a column capital in Piazza del Duomo. Climbing with a calzone is never a painless, mess-free endeavor, but there’s truly no better dinner view. Thirty feet up, I watch as the parade begins. A steady stream of middle-aged men trickle into the piazza, strolling and all on the phone. There is space enough for all of them to wander and never meet. This is the Italian conference, all the men communicating with each other over the phone, discussing the important business of the day, all the while practicing their birthright to mosey in solitude. Besides the conference call, there are a few dogs carefully leading their owners around the piazza’s perimeter, and the occasional selfie-sticked tourist snapping a picture before the church’s façade and getting nothing because the darkness of night is complete (with my help, naturally). Then of course there is the nightly investigation from the police. A police car pulls in and stops. An officer emerges from the vehicle turning to examine the piazza. He does this so quickly, however, like a ballerina, that I can’t imagine he sees anything. The officer returns to the police car and leaves. A night has not gone by without this courtyard ceremony. The phone callers keep about their floating during the inspection, never look to the police for a second. After my calzone on the capital, I write about the mysterious tragedy of Piazza del Duomo, the legacy of which, even decades later, necessitates this nightly check-up from the law.

It’s nearly 10 o’clock so I use my bakery paper bag as a parachute to float down to the ground. I walk across the now empty piazza, beginning the trip back to my room. At night, I repeat my day in reverse. Teenagers gather and stand around the popular cafés. They yell and giggle and move in socially practiced loops and circles like the waggle dance of the honey bee. As I walk past them I notice some of them quite look like bees, papery translucent wings and striped bellies. They don’t fly though. The adults sit in comfortable clusters drinking wine and snacking on Taralli. They seem quite unbothered by the night’s buzz.

I slip through the half deserted streets, avoid the crowds that attract the more aggressive street vendors who slip so many beads onto your forearms that your hands trail behind you to drag the dazzling weight. In a small and quiet piazza, I pass a man balancing on a block fallen from a stone. He has his hands outstretched to a brown cat. I’ve seen this cat many times on this very same wall and I know this could be trouble. The cat purrs and leaps to the ground. Once praying to the animal above, the man now bends below, losing balance and falling beside the wall. I turn to offer help but the cat steps between me and the toppled man. I nod and walk away. I exit via Porta Napoli, now shy and reserved in the darkness, pass the fortified wall who bellows out the decrees of the city (the same that once preached nothingness), weave through the chattering bushes there until I arrive at my place.

It’s dark in the hallway and I search for my keys which I can hear jinggling in some unknown pocket. I think of the workmen in Chiesa di Santa Irene standing there still. Finally locating the keys, I unlock the room and switch on the lights to find my wardrobe on the ceiling. Before putting away my poetry book I reread the days work. All the words are different, sometimes the language too, and parts are illegible and most of it is bad poetry. Of course I shouldn’t be surprised, as this has happened every day I’ve written in Lecce. But I still wish I could leave the city with one fragment of it. I know this is greedy.

I sit on my bed. The day has worn me, I recline like an ancient and tired statue, neck craned toward the wardrobe (a position usually reserved for particularly lovely churches). Wanting something to read, I nudge the wobbly cobwebby stack of books with my right foot which seems to have returned to me on my walk back. A red book with white chickens on it falls to the floor, William Carlos Williams. I’ll read this tonight. An anxious little black dot quivers in my eye, so I check up on the spider in the ceiling corner. It, like me, is worried about the wardrobe, although for different reasons. I can certainly go a day or two without studying Latin, but right now I’m tired and I’d very much like my pajamas.

Hæ Vala,

I don’t know how else to contact you but this essay is so beautiful! I am so surprised because I am also half-Icelandic but also half-Swiss (so I speak French) and was born in the US. What a coincidence! I am also a writer and went to BCB for a semester in 2017. I really enjoyed your observations from Lecce.