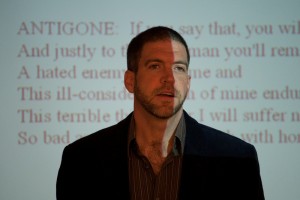

On the morning of November 3, 2010, AY and first-year BA students gathered to hear Dr. David McNeill deliver a lecture with the title, “Life, Death, and Antigone’s Autonomy.”

Dr. McNeill is no stranger to ECLA having once given a talk here in 2009. With a PhD from the University of Chicago, a BA from St. John’s College, and a recently published book to his repertoire of accomplishments, he is also involved in a research project at the University of Essex (‘The Essex Autonomy Project’). So there could not have been a more appropriate person to talk to us about one of the most perplexing and central issues in Sophocles’ Antigone: her strange relationship to the concept of autonomy.

Autonomy, McNeill clarified, consists of two sub-words in the Greek — ‘auto,’ meaning ‘self,’ and ‘nomos,’ translated as ‘law’ — which combine to mean ‘a law unto oneself”. The word ‘autonomous’ itself has only been used a handful of times in the past 500 years of Greek literary and philosophic tradition, one occasion being Pericles’ message of warning to the Athenians about the dangers of autonomy.

“We are familiar with being self-governing, self-regulating agents and contemporary modern and political theory has explicated the limits of our powers of self-determination,” said McNeill, giving us the example of the debate concerning whether an individual should be able to voluntarily choose death.

McNeill added that the Chorus connects Antigone’s uncanny relationship to life and death with the context of autonomy. It reveals the odd, incestuous begetting of Antigone and her siblings. Her actions could, as one reading of the text goes, be the result of a damaged personality deeply affected by a “self-generating coupling.”

The audience was asked to consider the possibility that it was not autonomy that led the protagonist to her end but the choices of her father. Antigone is then a victim of Fate. Regardless of this, she does share in an unhealthy connection to death, as exemplified by her obsession with her deceased brother and her repeated claims that she is already dead.

McNeill turned the argument on its head at this point and ruminated upon the possibility that Antigone’s autonomy is because of her relationship to life and death. Antigone defies Kant’s thesis on heteronomy, which discusses the subordination of will and adherence to an external moral agency, completely. She pursues her own desires and goes her own way. For example, she opposes King Kreon’s treatment of her brother’s body despite the legal and mortal consequences to which this leads.

The lecturer pointed out that part of Antigone’s indignation comes from Kreon’s failure to recognize the importance of the person who had died — perhaps if it had been someone else who had been denied a burial, Antigone would not have reacted so strongly or fought so valiantly for what she believed to be the right thing to do.

She seems to be concerned with intention rather than efficacy and this is demonstrated by disowning her sister Ismene when she refuses to help her in her quest. Evidently, Antigone does not believe she is doing anything wrong even as she suffers for her beliefs and actions. It seems strange, however, that someone who applies the ancient Greek wisdom that striving for the impossible is good, is punished for her actions.

McNeill left us to deliberate this paradox, which seemed to exemplify the many others we encounter everyday in real life. Equipped with humor and a world of referential knowledge, the lecturer made for a welcome addition to our day and our grand scheme of philosophic enquiry.