The program of the conference Pythagorean Harmonics from Philolaus to Leibniz, which took place on October 19-20th at Bard College Berlin, consisted mainly of scholarly lectures given by experts in their fields, which were as diverse as Greek philosophy, mathematics, music or art history. The participants discussed in an interdisciplinary framework recent discoveries or novel approaches in early Pythagorean number theory and music theory. To close the Saturday evening in the spirit of the discussion, Joulia Strauss, a versatile Berlin-based artist, sang and played ancient Greek hymns on what she calls the “Berlin lyre”.

Participants in the workshop first got to see Joulia when she gave her response to the opening keynote, delivered by Andrew Barker, a Professor Emeritus of Classics at the University of Birmingham. As a matter of fact, it was not difficult to notice Joulia in the crowd even before that – her distinct eye lines and extravagant black clothing accounted for that. “I am a reincarnation of an ancient Greek singer,” said Joulia in her response to the opening speech, which came as a surprise to the audience, because it was almost like a complete counterpoint to the (seemingly) secular tone of Prof. Barker’s keynote. Based on this first impression, we anticipated the spiritual touch of her evening performance.

The performance took place in the Factory, Bard College Berlin’s newly inaugurated building of art studios. We had to be quiet and enter the dark room one by one. Joulia stood at the door while performing a quick movement with her palms across everyone’s foreheads, as if she was cleaning something dirty from our souls. “Originally, I wanted to have a real fire outside, so that we could gather around and enjoy the hymns in the genuine atmosphere,” Joulia shared. Unfortunately, it was not possible despite all the efforts of Bard College Berlin’s administration, and so Joulia had to think of another way to summon in the performance the idea of a ritual. What she came up with was a symbolic clearing of people’s minds of all the unnecessary thoughts which, as she explains, are always present in our heads and prevent us from concentrating fully on the given moment. “We carry thoughts from the past and thoughts about the future. This is why we cannot be fully present, which is necessary to perceive the acoustic event with its entire impact,” Joulia explains.

“It really worked,” admits one of the students who gathered around Joulia after the performance to find out more about this particular ritual, among other things. “Sometimes I just have too many thoughts at the same time. There is something in the hand motion, perhaps something of your own, that brings you into a consciousness of the now,” said Jimena Guerrero, a first year Bard College Berlin student.

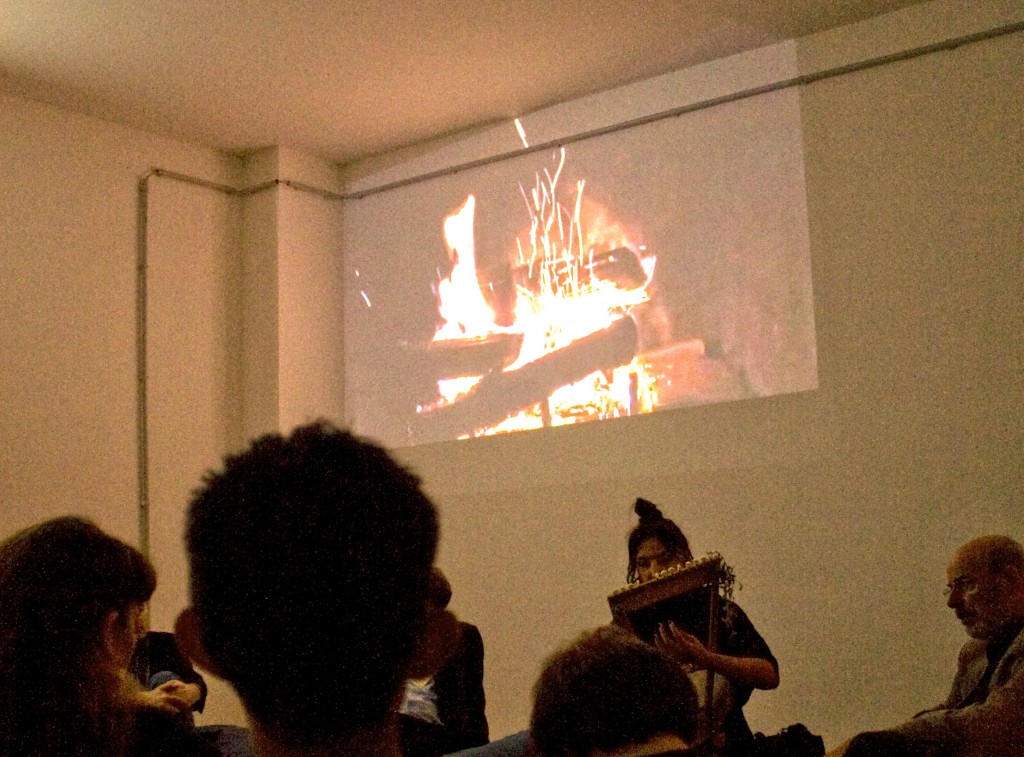

Although there was no real fire, an animation of flames was projected on the walls. Students and scholars from all over the world sat together in a quiet circle and listened to the bizarre rhythms. Joulia says that they are so interesting because of “the unique beauty of melodies, the multifaceted and mathematically genius structure of the modes.” They never repeat and they include intervals no longer common to our ear: third tones and quartertones. “Their rhythm is determined by the Ancient Greek language. It is complicated to keep singing. For me they are a perfect model for the structure of the First Global Revolution,” she adds.

What does she mean by “the First Global Revolution”? “Modes of music, such as hypodorian, dorian, mixolydian, hypolydian, lydian, hypophrygian, and phrygian are connected through common tones, the modulating points, and yet nothing in the world can distract their specific characters. A “modulating point” is what connects different movements; it is solidarity and “love for the resistance of the other” (a term by Daniel Mützel). What differs in the movements is the irreducible, unique, real experience of the moment when a movement emerges. The archaic tunes are a legacy of a horizontal multiplicity and respect towards difference. This difference was suppressed by the Athenian State, which emerged with the classical period, continued as the Roman Empire and ended up with capitalism. The relation of elements constituting the First Global Revolution is based on balance and harmony.”

Joulia acquired her knowledge about Ancient Greece mostly through encounters with its art. She first became introduced to it when she joined the Platonist St. Petersburg New Academy of Fine Arts in the 90s, where she became one of the head figures of the “new academism” – a movement that the queer society of the institution established. She studied in St. Petersburg in light of her Russian origin: she comes from the Mari El Republic, a region which has a strong pagan and spiritual tradition. Joulia thus has a unique background – both her mother and grandmother were engaged in preserving the Mari heritage and pagan faith, and thus she is the third generation of “Mari witches,” resisting the oppression of the Orthodox Christian state. Although in St. Petersburg Joulia was trained in Greek sculpture, it was actually through mathematics and media that she became involved with Greek music some years afterwards:

“In 2008 I was working on the graphics of the book of my deeply beloved colleague, a media philosopher Friedrich Kittler, called Music and Mathematics 1. Hellas 2: Eros. This book, as well as the first one in the series, Music and Mathematics 1. Hellas 1: Aphrodite, is the last word in the Berlin philosophy (externally labeled as “The German Media Theory”) and it is deeply Pythagorean. One of the images was of very bad quality and I had to draw a new one. It was a representation of a song by Mesomedes calling a muse (P.261). Suddenly as I was working on the image, I realized that, knowing how to read ancient Greek, I could sing hymns that were more than 2000 years old, which was very exciting. At that time, one of the outstanding participants of the Bard College Berlin workshop, Martin Carlé, was working on reconstructions of the ancient Greek tunes with the help of a simulation technology. Together with another extraordinary participant of the BCB workshop, Gerald Wildgruber, we decided to construct a real musical instrument. After a very adventurous period of constructing it, I could finally start to play.”

After Joulia performed and we were still sitting on the floor in the dark room, she shared a couple of stories and experiences, each more interesting than the other. For example, she told us the story of the instrument she was playing, the so called “Berlin Lyre”: “The instrument was made in a studio called Klangholz. I and Martin Carlé borrowed it from them, but we never returned it. Instead, we added to the original instrument five strings. Not long ago, a close friend of mine, Werner Gutmann brought me back to the studio, because of some technical difficulty, and I found out that the master of the instrument had passed away. No one in the studio was angry that I still had it. I played the hymns to them and they seemed very happy about it.” But the name of the lyre actually got established when Joulia played it in Athens; the Greeks were curious about this upgraded instrument she had brought, and so she told them it was “the Berlin Lyre”.

As a versatile artist whose main field is visual arts, Joulia admits that sometimes, there might be longer periods when she would not get to play the hymns. She says that she performs “when the moment (Καιρός) comes. Sometimes, it is at Tate Modern in London, sometimes at an event of great gravity, like the funeral of a precious friend. And, of course, in the streets – in this video, I performed to the police in Athens for educational purposes.”

Joulia says that what she likes most about playing the hymns is “the out-of-body experience of oneness with the world. The experience of me and the audience being one in the sound.” Thanks to this “oneness”, the evening performance was definitely the most harmonic moment of the workshop. Although I cannot speak for everyone, I admit that the performance was quite an “out-of-body experience” for me, personally, which, I imagine, could have been provoked only by such an extraordinary person as Joulia. She was daring, crossing borders, and creating her own notions – and that makes her a prototype of the ideal element to inspire specialists to dare cross the borders of their fields, which was an important idea behind the whole event. I think that the moment when an artist with a pagan background and well-respected scholars are in perfect harmony confirms that attempts to combine disciplines do not come in vain.