A few days before this year’s International Day for Women’s Rights, I came to the realization that I could not attend the annual Berlin Women’s Day demonstration as I had to give a presentation for my course on the 8th of March, Marx Yesterday and Today. Instead of marching for Women Workers’ Rights, I could only discuss theories of labour in an academic setting. Protests are one of the few things that I can say are “my thing,” so I found myself feeling very disappointed at not being able to take part in a demonstration that advocated for a matter with which I am so intimately concerned.

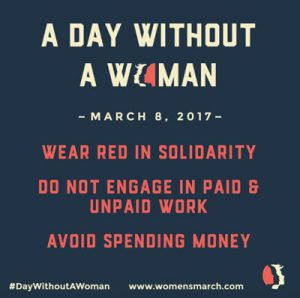

Berlin was, of course, not the only city that honored the day that marks the continuous struggle for women’s equality. Polish women marched for equal rights, protection against violence, and respect. Yemeni women protested outside the Saana UN offices for peace in their war-torn state. Mexican women painted black crosses on pink backgrounds to commemorate women who have gone missing or been killed. In many cities in the United States as well as in other cities worldwide, the “A Day without a Woman” strike imagined the effect of the absence of women on the economy. Women who participated were encouraged to (1) not engage in any paid or unpaid labour, (2) refrain from purchasing any goods not from small, women or minority owned businesses, and (3) wear red to show support. While the last principle is symbolic, the first two are directly impactful. Sadly, some of the rallies faced police backlash, leading to the arrest of 13 New York activists for “civil disobedience.” As in many other instances, fights for equality were met with institutional retaliation. This is exactly why most 8th of March protests specifically attacked institutionalized sexism.

Unlike all of these wonderful women, I was not able to do as much to show support for our cause. So I am writing this article as an alternate form of activism. Even though I couldn’t be in the streets, I adhered to both the economic principles and the dress code of “A Day Without a Woman.” I painted my nails red and wore the only item of red clothing that I own — an above-the-knee red skirt that ironically caters to the male gaze while showing solidarity with a movement for gender equality.

But, of these various demonstrations, the one that most struck me on this year’s Women’s Day was the one that took place in my home city of Skopje in Macedonia. Though I will always show solidarity towards women’s struggles in an international context, I will likely always feel a more selfish kind of affection for the issues concerning Macedonian women. The sexism inherent in Macedonian culture has shaped my views on feminism and my own internalized misogyny. In this article I intend to show how political discourse on the levels of architecture, propaganda and laws shapes gender reality in Macedonia.

For the majority of my childhood, the 8th of March was presented to me as Mother’s Day. It was sometimes also conceived of as the day you suck up to your female middle school teachers with average-looking flowers and cheap jewelry. So seeing Macedonian women (and men) of different ethnicities standing together under umbrellas with protest signs, demanding better treatment of women was wonderful, even if it was only seen through my computer screen. When looking at reports of the demonstration, I recognized some of the activists who I marched with last summer under the rain and sun alike — only then we had opposed broader political corruption.

Just as the protests happening a few months ago, this one sought to hold government institutions accountable for their legislation, focusing on reproductive rights and adequate legal responses to domestic violence. One sign in particular captured how this demonstration tackled cultural norms that have been perpetuated by the state: “Oppression of Men is a Tragedy. Oppression of Women is a Tradition.” Indeed, VMRO-DPMNE, the right-wing party that has been in power for 11 years now, has long used the excuse of tradition and family to perpetuate sexism and oppression – a textbook conservative strategy.

Macedonian politics are complicated to put it mildly, and, in my biased opinion, more absurd than the current Trump administration. The most salient example of the Macedonian administration’s absurdity is its implementation of project “Skopje 2014,” which, in addition to all else that makes it problematic, blatantly promotes sexist ideals. Arguably the most ridiculous and economically damaging governmental projects that has ever been enacted in Macedonia, “Skopje 2014” is an architectural endeavor that has resulted in the building of 137 objects in a Baroque style. The Baroque style has never before been present in the Balkan region, yet this project purports to represent Macedonian history. Marketed as a “tourism booster,” about 671 million euros were spent on the project — an amount of money that can not possibly see its return from tourism for decades to come. The aesthetic failure and money laundering of “Skopje 2014” aside, the project’s almost neo-fascist-looking style of “art” sends charged messages about the (problematic) values that Macedonia celebrates.

A great portion of the project’s objects are statues and sculptures of variations on soldiers and warrior figures. The 12 meter tall fountain of Alexander the Great placed in the main city square is now the central object of the city. Only about 50 meters away are the figures of Goce Delcev and Dame Gruev – two revolutionaries who fought against the Ottoman colonization of Macedonia – who, like Alexander, are placed on horses in a militarized manner, even though it is unclear whether horses were involved in their operations. In the middle of a roundabout near my apartment there is yet another man, whose name I had not heard before the project, on a horse. The list of these “historically important” men on horses goes on and on and even includes those who may have committed crimes, reinforcing an all too familiar brand of nationalism as well as celebrating the ever-present toxic (Slavic) masculinity.

Depending on how you count them, there are only about 20 female figures represented among all of these sculptures and statues. Even the unartful “Bridge of Art” that features 30 kinds of artists — from painters to writers and musicians — does not have a single woman. The most significant woman represented in this project is Olympia, Alexander’s mother. She does not even have her own monument: Rather, she is a part of Alexander’s father, Phillip II’s, object called “Warrior”. In this constellation she is represented as a mother figure, holding her child in a very feminized pose, clearly subordinate to her husband. The message that this object sends is obvious: The only important role for women in Macedonian society is that of the mother, and even then, that role is not as significant as any role that the man plays. The overrepresentation of men in this project reinforces attitudes that are already held by much of Balkan culture. Masculinity is celebrated to the point where it is toxic to men and women alike, femininity is barely given a space to exist, and — in the limited space given to them — women are not allowed to be anything but feminine.

However, in Macedonia sexism does not only play out in the public sphere. The government goes to extreme lengths to send blatantly gendered messages, reinforcing these sentiments. One of the forms that VMRO-DPMNE’s propaganda takes is that of borderline moronic advertisements promoting bigger families and shaming abortions. These advertisements are broadcasted on both the national TV station as well as many of the government influenced and controlled private TV stations. My dad, rightfully so, calls these commercials “an insult to [his] intelligence” whenever one comes up on our TV screen. One ad has images of a sweet, blue-eyed baby with a voiceover saying “If you think that the violent termination of the pregnancy is the only solution, then you have to be aware of the consequences.” It then proceeds to purposefully distort the risks of a medical abortion, alluding to “anesthesia complications” and “infections that can cause sterility” — risks that are not so serious in today’s abortion practices. Another features a young, presumably unmarried couple who find themselves with an unplanned pregnancy where the potential mother wants to keep the baby while her boyfriend doesn’t; the thing that ends up convincing him to keep the child is her saying that she senses “It’ll be a boy” and look like his father. And, of course, there is the ad with the patriarchal, ex-capitalist grandfather who tells the story of how he lost all of his material wealth and has come to the brilliant realization that his family is his real wealth. Indeed, my dad and many other Macedonians have the right to feel insulted by this anti-choice propaganda that ends with the words “You have a choice: Choose life.”

All of these gendered government attitudes eventually translate into your more than slightly embarrassing older male relative telling you to go help the women in the kitchen, explicitly stating that the reason he’s asking you to do it instead of your brother is because “you’re a girl.” They translate into harmful anti-abortion policies. Truthfully, I wasn’t entirely sure about how these laws worked in Macedonia until I found and read a 14 page hurdle-filled legal document online titled “Law for Terminating Pregnancy.” The first problem of this document is the fact that the word “abortion” is never even used. Instead, the medical euphemism of “terminating pregnancy” is repeated over and over, stigmatizing the process even more, even though on the first page it literally says it is “the free choice of the woman” and that an abortion can only ever be carried out “for the sake of her health and well-being.” This law, unsurprisingly, is not trans-inclusive (Macedonia is not the friendliest place when it comes to LGBTQ rights) and does not acknowledge that people other than cisgender women i.e. trans men and nonbinary people can also experience pregnancy. Furthermore, the law states that a woman may only have an abortion in the first 10 weeks of pregnancy and, bizarrely, cannot have another abortion if she had one the year before. However, the most disturbing part of the law is the way its bureaucracy is structured to shame women for their choice. If the pregnancy is under 10 weeks, the woman has to send a written request. After this gets approved, she has to wait 3 days for the procedure to be performed. In this time her doctor is required to provide her with counselling and information about the possible “benefits of pregnancy” and “risks of the procedure.” Not only is the language of this law blatantly anti-choice, but its proceedings only add to the difficulty of the already psychologically burdensome process. The law gets even more Kafkaesque in the case that the woman is more than 10 weeks into her pregnancy or the woman is deemed to be medically unfit to get an abortion. The woman then has to go through two committees to maybe be able to get approval.

With all of these obstacles, abortion still remains technically legal, even if it is to be a shameful and difficult experience. But who is it most difficult for? If you are well-off, then you could either get a connected doctor friend to help you out — a common practice in the Macedonian medical field — or you could simply be more likely to get the time off work to go through the legal nonsense. The women who have the hardest time accessing abortion services are lower-class women who work long hours for low wages, who live in poor rural areas, who are a part of marginalized minorities (such as the Roma), and who cannot afford transportation to one of the bigger cities.

But sexism already existed before VMRO-DPMNE came to power and before all this legal nonsense was implemented. Macedonia, as virtually every other country on Earth, has always been a patriarchal one, and it is unlikely that it will stop being that any time soon. Yes, of course we need to fight sexist attitudes in our everyday conversations, the way we raise our children, and the way we interact. However, we must follow the example of the activists of the 8th of March Skopje protest and incorporate the opposition to institutional oppression and laws into our feminist discourse, battling issues communally rather than individually. If we do not address sexism on a systemic level through voting, campaigning, running for office, protesting, and civil disobedience, the war against sexism cannot possibly be won.

Notes:

1. Women’s March https://www.womensmarch.com/womensday/

2. Amatulli, Jenna. “Women’s March Organizers Arrested During ‘A Day Without A Woman’ Rally.” The Huffington Post. March 9, 2017. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/womens-march-organizers-arrested-during-a-day-without-a-woman-strike_us_58c05a70e4b054a0ea67587e

3. [Gallery] “Fight Like a Girl” Every Day, Not Just on the 8th of March ([Галерија] „Бори се женски“ секој ден, а не само на 8 Март.) Radio MOF. March 8, 2017. http://www.radiomof.mk/galerija-bori-se-zhenski-sekoj-den-a-ne-samo-na-8-mart/

4. Skopje 2014 Under Close Examination (Скопје 2014 под лупа.) Prizma. April 12, 2017. http://skopje2014.prizma.birn.eu.com/mk

5. “Law for Terminating Pregnancy” http://www.healthrights.mk/pdf/Pravnici/Domasno

This is a demand for better and no matter how little people want to be ruled out.